Penman for Monday, November 3, 2014

A COUPLE of weeks ago, walking from my sister’s office in downtown Washington, DC to the library of the George Washington University, I paused at the corner of 19th and I (or “Eye”) Streets, and was overcome by a sense of déjà vu. I vaguely recognized the place, but something had changed—the old Presidential Hotel was no longer there, replaced by the Presidential Plaza, a grayish, nondescript commercial building replicated on a hundred other blocks in the city. It was what had stood at that spot that I suddenly missed: the hotel, built in the 1920s—and me, more than half a lifetime younger and suitcase in hand, looking up at my first American abode.

It was September 1980, I was 26 years old, and I was on my first foreign trip—to the United States, no less, thanks to a generous and visionary boss who thought that a budding writer like me could benefit from some exposure to the outside world. He arranged for a grant that would introduce me to media organizations and practices in various places in the US for three months, and within a month of being told that I was leaving, I was—all gussied up in a scratchy double-knit suit, which was what I thought any Stateside-bound traveler worthy of respect was supposed to wear.

After stops in Honolulu and San Francisco, I arrived in Washington on a nippy autumn morning. My first American mystery greeted me in a sign just outside the airport: “PED XING.” What on earth did that mean, I thought—could there be so many Chinese in Washington? I took a cab to my hotel, the Presidential on 19th and I, and was met by the doorman, who suspiciously resembled—and indeed was—a kababayan. I felt instantly relieved. He seemed happy to see me as well, and after effusive introductions and references to the motherland, he showed me to my room, up on the fifth floor.

Unable to sleep, I stepped out, still in my suit, and surveyed the streets around me. I got hungry and saw a classy-looking restaurant at the corner. I had several hundred dollars on me—partly my allowance, and partly my life savings—in cash; I felt rich. I stepped into the place, and ordered quarter of roast chicken. It cost me eight dollars, and I dutifully tacked on a 15% tip, like the guidebook said. I walked around the corner to K Street, and saw a luggage store; I walked in, and all too quickly fell in love with a saddle-leather Schlesinger briefcase. “How much?” I asked. “One hundred dollars,” the lady said. “I’ll take it!” I said, and forked the cash over; it would be eight years before I would get my first credit card, but that’s another story.

I walked back to my hotel, feeling very businesslike with that briefcase that smelled positively posh, and just outside the hotel, on the bus stop along the sidewalk, I noted my second American mystery: another sign that said “No Standing.” How was one supposed to catch a bus or a cab, I wondered, if they couldn’t stand there, and I couldn’t see any seats, either. I fell asleep that afternoon, with the Schlesinger beside me in bed, only to be woken up by a loud rap on my door. It was my kababayan the friendly doorman, and it must have been past nine in the evening. “Padre,” he whispered, “could you lend me twenty dollars? I have a hot date tonight and don’t want to disappoint her, I’m just a little short!” He winked conspiratorially, and I slipped him the twenty, and went back to bed.

Many more interesting things would happen to me during that visit, but that was the last I saw of my new kaibigan and of my twenty bucks. The next day, I went back around the street to look for a breakfast place, and saw my first McDonald’s. It was my first American fast-food experience, and I felt flustered by the array of comestibles on offer overhead. Forgetting for a second where I was, I glanced at the two Pinoy-looking ladies in the line beside me and asked, in Tagalog, “Miss, paano ba umorder dito?” and they told me how. They turned out to be secretaries at the World Bank. Later that day, when I told the cook at the cafeteria in our sponsoring institute about my eight-dollar lunch, she laughed and said, “You shoulda framed that chicken!” before serving me a full meal for $2.50.

Since I was going to be in Washington just briefly being flying onward to my main destination in East Lansing, Michigan, I resolved to make the most of my visit by touring as much of DC as I could. Our daughter Demi was just six years old, and I sent her postcards and pictures that I took of squirrels running around the White House lawn. Outside the Smithsonian, I lingered before the souvenir carts before choosing a tall ceramic (at least that’s what I thought) mug that said—what else—“Souvenir of Washington, DC” and featured the relief facade of the Capitol building. (I would later discover, back in Manila, that the mug was made of plaster, and made in Taiwan.)

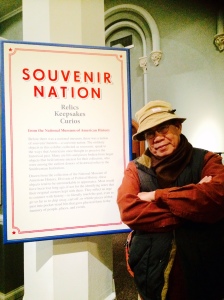

All these came back to me as I stood at that corner of 19th and I, feeling a little foolish but feeling even luckier to be alive at all and back in the same spot, much bulkier from ingesting untold hundreds of chickens and Big Macs since then, but not all that much the wiser. And as it happened, when I walked the other day into the Smithsonian Castle, on exhibit was “Souvenir Nation”—a show of how people have kept pieces of the past to form their own personal histories.

I’m over souvenir mugs, but I still keep that Taiwanese token on a shelf back in Diliman as a reminder of one’s innocence or stupidity—one or the other, although I can be fairly sure by now that there’s hugely far more of the latter in Washington than the former. And I still have the Schlesinger briefcase, all beat up as it should be after 34 years, but still handsome in a rugged way, which is more than can be said for its owner. No, I’m not over fine leather briefcases; I saw the very same case on eBay last week, selling slightly used for $25, and I snatched it up to replace the old one—as a souvenir of this great and wondrous city of Washington, DC.