for the Star’s 35th anniversary, July 2, 2021

WHEN THE Philippine STAR was founded 35 years ago, we were still enveloped in the euphoric glow of having successfully deposed a dictator peacefully and installing an icon of democracy in his place. I was one of that happy throng on EDSA celebrating what we believed was a new dawn of hope, a fresh opportunity for our people to grow in freedom and prosperity. Like many writers, I ran out of metaphors and superlatives to describe that moment, which seemed nothing short of miraculous.

Nowadays it has become commonplace—indeed even fashionable in some quarters—to revise and reject that narrative, and to claim that it was a foolish mistake to have replaced a seasoned politician with a rank amateur. Martial law wasn’t so bad; no wanton thievery took place; only a few were hurt for the good of the many; we were never so disciplined, and our streets were never so clean.

How we came to this point—like the resurgence of Nazism in Europe and of racism in Trump’s America—is for me the great mystery of those 35 years, an arc of sorts marked by Cory on one end and by Covid on the other. There’s certainly no pot of gold at the end of this rainbow, as should happen in fairyland—which we rather quickly realized, right after EDSA, was not where we were.

For some such as Jose Rizal, Alexander the Great, Wolfgang Mozart, Manuel Arguilla, Bruce Lee, Eva Peron, and, yes, Jesus Christ, 35 years was a lifetime. You could have been born in a hospital while the tanks were massing at EDSA, and died this year of Covid, gasping for breath in that same place. Had that happened to me, I would have protested and pleaded, albeit inaudibly through my tubes, that it wasn’t fair, that I deserved a peek over the horizon, at least through to the May election, to see if it was worth the wait—or not, and then slink into sullen slumber.

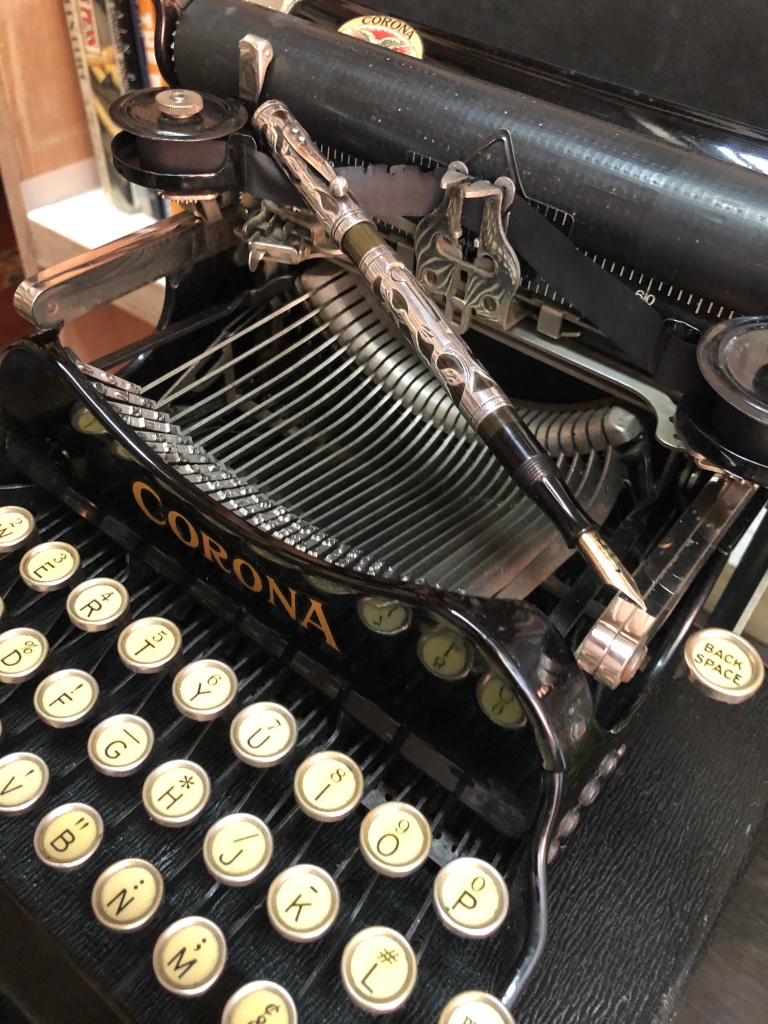

During that time, I grew from a young father and a writer on the verge of a teaching career to an aching retiree surrounded by old books and creaky machines, and I have to wonder if our nation fared better and learned as much. Or should I say “unlearned”? At EDSA I learned to hope, to trust in the ideal and the good again, to have positive expectations of the new century looming ahead. FVR and his “Philippines 2000” thumbs-up may have seemed hokey at the time, but there was a genuine spring in that step, a sense of things going in the right direction. And then they began falling apart, the old mistrust and suspicions returned, and we took one president down and nearly succeeded with yet another.

But it wasn’t just us. The closing decades of the 20th century were a time of sweeping changes all over the world. Soon after Marcos fell, a tide of reform and revolution washed across Eastern Europe and eventually into the Soviet Union itself; that union collapsed, the Berlin Wall fell, and it seemed like the era of dictators and despots was over, but it was not. With Hong Kong in its navel, China morphed into a commercial colossus, proving that freedom and capitalism do not necessarily go together. The 1997 financial crisis shook the planet.

After 9/11, whatever remaining hopes we had of a better new century vaporized, and the new specter of terrorism now stalked the globe. Barely had ISIS retreated from the sands of Syria when a new and even more insidious plague, Covid-19, threatened to annihilate mankind.

Others will remember this period as the age of cocaine, corporate greed, mass shootings, and, generally speaking, a culture of excess, of over-the-top indulgence on whatever floated your boat: drugs, sex, money, power, toys. Very few people had actual access to them, but the media—that’s another whole story—kept glorifying vice as virtue, until many began to believe it well enough to dream. It was Dickens’ “best of times and worst of times” all over again.

That would be the sober—and sobering—summary of what tomorrow’s history books will be saying about those decades. But of course—and thankfully—it wasn’t all politics and the misery that often comes with plays for power.

There’s a part of me that wants to tell the story of these past 35 years as the rise of consumer technology toward near-total domination of our daily lives. Humor me as I recall little vignettes to show what I mean.

When the EDSA uprising broke out, we heard the news over a big black Panasonic radio-cassette player that I had picked up years earlier at the Zamboanga barter trade place (along with the obligatory sotanghon and White Rabbit candies). It was—beside our 12-inch, black-and-white, red plastic-bodied TV—our news and entertainment center in the boonies of San Mateo. It sat on our dinner table, accompanying our meals like a permanent guest, sometimes directing the conversation.

When it spewed out the news that something dramatic was taking place at EDSA, and when we heard Cardinal Sin calling on people to go, we knew we had to. Not long after, we piled into my VW Beetle, turned on its radio for updates, and headed for the trenches. For the next few days or so, radio was king, whether at home, in your car, or in your pocket (yes, boys and girls, there was pocket radio; TV was around but only the coolest people had portable versions).

I missed out on most of the Cory years because I went to America for my graduate studies, and there I became anchored to the payphone for my calls home, clutching a handful of quarters to feed the machine. I had hand-carried an Olympia typewriter to write my thesis on, but then I discovered computers, and in 1991 I lugged home a 20-pound behemoth with all of 10 megabytes to fill up. I felt like a gunslinger—I was going to write the next Noli, protect the weak, and get justice with one floppy disk after another.

Nothing would define the ‘90s more than the personal computer, and I soon equated the machine with creation, the blinking cursor with a challenge to produce. I drooled (and lost the plot) when I watched Scully and Mulder hunched over a super-sexy PowerBook 540c in the X-Files, and when I got my own, it was like Moses receiving the tablets—with a trackpad and an active-matrix display.

Soon another gadget emerged with which we felt even more tethered to some central brain: the pager, whose insistent buzz enhanced our importance, even if it all it asked was where you were and could you please come home. Fake news had yet to be invented as a cottage industry, but a lot of it, I’m sure, went through EasyCall and PocketBell.

By the time the next EDSA happened, we had something far snappier and more personal than radio with which to undertake regime change. Yes, I was now writing speeches on a Mac, but the messages flew thick and fast on a new gadget—the cellphone. If EDSA 1 succeeded because of radio, this iteration flew on the wings of SMS, the millions of texts (the jokes, the rumors, the calls to action) whose accretion would spell the end for an inebriated presidency.

As it happened, 2001 would be memorable for another image seared into our consciousness: the collapse of the Twin Towers, brought to us slightly delayed and in full color by satellite TV. We’d had TV before, of course, but had always seen it more as Comedy Central, a box to gather the family around. CNN changed that, and brought the world’s torments to our living rooms. Cheaper TVs, one in every room, had long fragmented the family, especially when Betamax and VHS, the precursors of Netflix, became available.

A few years later, a cellular phone call and a recorder almost took another political giant down, causing millions to gasp and laugh as the tape was replayed on TV and radio over and over. “Ang importante hindi madamay yung sa itaas,” said a female voice, which was exactly what happened. That year, 2005, was also the year a platform called YouTube was born—and thanks to YouTube, the tape can still be heard, for all digital eternity.

Indeed, video, the Internet, and social media would soon change the political and cultural landscape, not just here but the world over, although the Pinoy—perhaps in response to that elusive quest for Olympic gold—has towered over much of humanity in terms of Facebook usage (and earlier, in SMS transmissions). One way of putting it would be that we are the world’s champion usiseros and chismosos, resorting to Twitter or Instagram at the merest hint of an idea, no matter how malformed.

Today we have an abundance of information and information sources at our disposal—and yet we seem to be as ill-informed as ever, with opinions shaped and manipulated by Sith Lords in the Dark Web. Dismissing newspapers and editors as gatekeepers of the truth—which not all of them have been—we create our own versions and peddle them instantly for a thousand “likes,” the supreme accolade of the early 21st century. Most others might prefer to be simply receivers and forwarders of whatever crosses their screens, the passive agents of mindlessness.

Thirty-five years ago, we drove to EDSA on pure conviction that it was the right thing to do. Without Twitter or even SMS, no one could tell us “Right on!” or “Me, too!” We listened for scraps of news and turned them over and over in our hushed minds; we could be killed; we could be free; would our friends be there; what else did we study for. It was a long drive from San Mateo to my in-laws’ place in Project 4, where we parked the car and walked to EDSA. It was a lot of time to think.

Thirty-five years is a lot of time, but looking around today, with Filipinos still dying by the gun or by drowning in one’s own fluids in some alien hospital, I have to wonder how this narrative arc from Cory to Covid will end—or how much longer it will go, at least in my lifetime, which naively still yearns for a happy ending.

Penman for Monday, August 5, 2013

Penman for Monday, August 5, 2013