Qwertyman for Monday, October 13, 2025

IF SEN. Alan Peter Cayetano and his cohorts in the Senate minority wanted to rile the people even more, they couldn’t have done it better than by having Cayetano challenge Sen. Tito Sotto for the Senate presidency, at the same time that he was floating his supposedly heroic idea of having all elective officials resign because the public was fed up with them.

He had to know that that was exactly the kind of antic that made people throw up at the mention of certain names—a dubious pantheon of the corrupt, the bought, and the compromised. But he did it anyway, employing his imagination to yank public attention away from the burning issue of the hour—the massive flood control scam and its ties to many lawmakers—in the direction of Mars, and the possibility of honest (never mind intelligent) politicians inhabiting that planet.

Why he did that is anyone’s guess, but mine would be that anything to stop the momentum building up at the Blue Ribbon Committee under Sen. Ping Lacson was good for the minority, many of whom were increasingly being threatened by the exposure. If Cayetano had resigned first (and forthwith!) to provide proof positive of his noble intentions, the distraction would have been worth our time, but of course that was never part of the plan.

The plot to unseat Sotto—brazen and shameless in its purpose—was more credible and worrisome. It fizzled out but remains potent, simmering just beneath the surface. Lacson’s resignation as BRC chair was probably a concession to forestall Sotto’s, but the situation in the Senate is so volatile that it can’t take much for the leadership to switch while we’re brushing our teeth.

All we seem to be waiting for is that point of utter desperation when the beleaguered, fighting for their political lives and possibly even their personal freedom, ignore all considerations of decency and public sensitivity, weasel their way back into the majority, and deliver the Senate to its most famous watcher from the gallery: Vice President Sara Duterte, whose fate still hangs in the balance of an impeachment vote that has yet to happen.

That vote and its implications, let’s all remember, was what triggered all of this. Premised on rampant corruption within her office, her impeachment, had it passed the Senate, would have barred her from running for the presidency in 2028 (and, for PBBM, from the resurgent Dutertes wreaking retribution on their erstwhile allies). But this isn’t really just about Sara—it’s about all those other trapos who’ve cast their lot with her, whose fortunes depend on her absolution in the Senate and ascension to the Palace.

Former Senate President Chiz Escudero, who dragged his and the Senate’s feet in that process, has now dropped all pretensions to impartiality, calling the impeachment “unconstitutional” in a speech that would only have pleased the Vice President, a title he himself might be auditioning for. He did his part well, with what many saw to be the ill-considered assistance of the Supreme Court, to freeze the impeachment complaint.

And there that matter sat, until PBBM—whether unwittingly or presciently—(and here we’ll go fast and loose with the idioms) shook the tree, opened a can of worms, threw mud at the wall, and unleashed the kraken by exposing the trillion-peso infrastructure scandal now rocking the country. He might have done this to suggest a link between the alleged corruption in the VP’s office and even larger acts of plunder emanating from her father’s time in Malacañang, a deft political move. But reality overtook his imagination, and now the issue’s grown far beyond that into his own administration, his own responsibilities, his own accountability.

That said, and however we may have felt about him, PBBM has done us all a service by drawing the curtain on the systemic rot in our society and governance, for which he, Sara, and their cohorts have all been culpable, directly or administratively. By doing so he rendered himself vulnerable as well, and the VP’s forces are now zeroing in on that vulnerability to deflect attention from their own predicament.

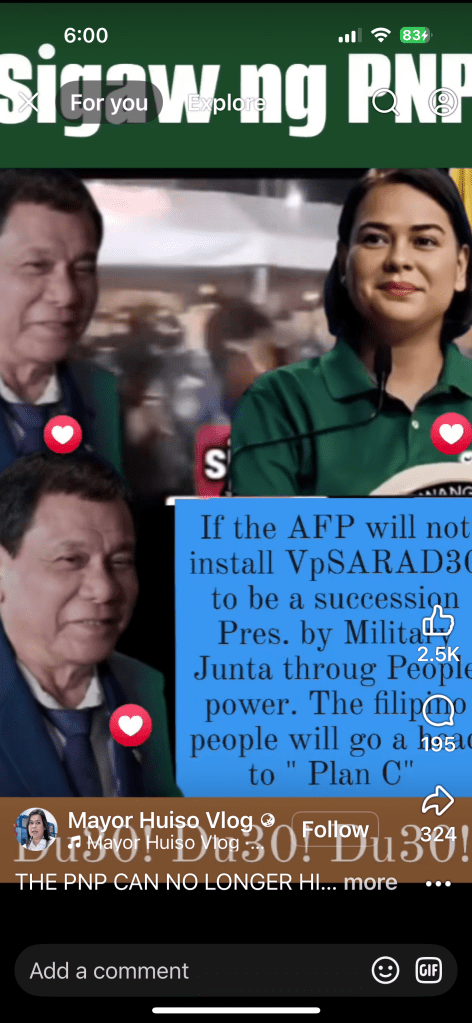

Thus the barrage of “Marcos resign!” calls (as opposed to the Left’s “Marcos and Duterte resign!”), which has become shorthand for BBM out, Sara in. (It was on that key point that the rumored September 21 coup plot reportedly first stumbled, with the plotters balking at the alternative.) It also explains the slew of professionally produced reels on Facebook and other social media calling for the military to depose the President—ironically, something so openly seditious that Digong Duterte’s NTF-ELCAC would have instantly pounced on them, but which BBM and his crew seem to be shrugging off, at least for now.

What tempts our imagination in this fraught situation—where public trust in our politicians and even in the courts is hitting critical lows, and where no clear and short path to change seems visible until 2028—is the possibility of military intervention, whether by martial law or on its own volition. I’ve been assured by friends who know better that this military of ours today is much more professional in its mindset than its predecessors, and that it will abide by the Constitution. I sincerely hope they’re right, because if there’s anything that all the parties in this mess can probably agree on, it’s that boots in the streets won’t bring us any closer to a functioning democracy.

I’m reminded in this instance of one of my favorite literary quotations, from Mark Twain who said (in so many words) that “Of course fact is stranger than fiction. Fiction, after all, has to make sense.” If you had told me three years ago that we are now relying on a dictator’s son to save us from an even worse alternative, and in the process—if almost by accident—expose corruption so foul that we are back on EDSA demanding not regime change but the rule of law, I would have called you a lousy fictionist with a runaway imagination. Yet here we are.

Literature, especially poetry, finds its ways of seeing things done:

Cry plunder and let loose…

Poetry finds the power to do a Schrodinger and go meow in quantum bits—and stultify Aristotle and Twain.

Or, maybe more precisely, the last paragraph of Q’man 167 is also the case of a poem’s tell of three years ago having sprung a fictionist’s correlative in the light of current events.

Show-and-tell goes well for fiction and poetry, but our scientific papers and laboratory experiment reports should stay within the boring bounds of show-don’t-tell.