Penman for Monday, January 16, 2017

ASIDE FROM the fountain pens which I’ve recently stopped collecting, I’ve long nursed another, quieter passion, albeit on a much more modest scale. Since my grad-school days in the American Midwest in the 1980s, I’ve been drawn to old books from and about the Philippines. Sadly I can’t read Spanish—one of the great regrets of my college life, a casualty of our generation’s sweeping rejection of everything that smacked of colonialism (except, ironically, English)—so my pickings have been confined to books in English, largely from the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

I stumbled on the first of these books—and began to be conscious of their significance—while I was poking around antique and thrift shops for pens. The Midwest, with its many universities and industries (not to mention pen companies like Parker and Sheaffer), was a cornucopia of all things old and wonderful, and inevitably my eyes would drift to the dusty bookshelves that typically carried cookbooks, old Bibles, local lore, and Western novels.

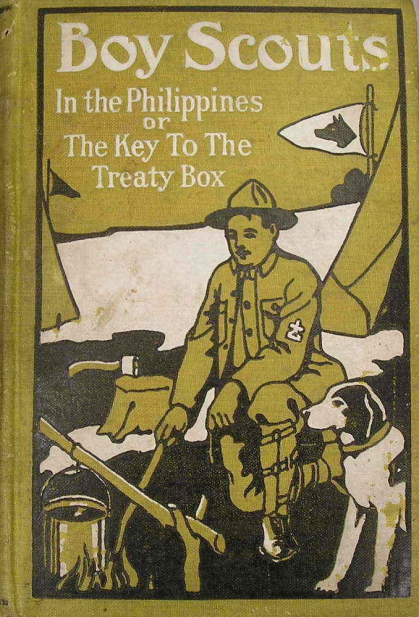

Now and then, however, I’d get lucky and come across a book with some Philippine connection, usually from around the early years of the American occupation. With titles like Uncle Sam’s Boys in the Philippines and Our New Possessions, these books celebrated American imperialism, the novel fact that it now had a colony across the Pacific that deserved to be introduced to curious readers in Kansas and Missouri.

I remember finding the massive two-volume Our Islands and Their People for $10 in a Milwaukee antique store, only to have to leave them behind when I flew home from graduate school in 1991. But I did bring back a small trove of similar material, and have added to them since then, largely via eBay.

My Holy Grail had been a first edition of Carlos Bulosan’s America Is in the Heart (I would acquire one later locally in the most interesting circumstances—I’ve told the story here—and would give it to my daughter Demi as a wedding present), but another precious book I was relieved to have saved from the Faculty Center fire by foolishly leaving it in my car is a first English edition from 1853 of Paul P. de la Gironiere’s The Adventures of a Frenchman in the Philippines, an eBay pickup from the UK.

I’m not an antiquarian by any means; I lack the vision, the resources, and the scholarship for that. To be honest, I haven’t even read everything I’ve collected, a pleasure I’m saving for my impending retirement. I just like salvaging these well-worn volumes from the scrap heap, or from some dark corner where they can’t possibly be appreciated. They’re neither particularly rare nor valuable—only two or three have cost me more than $100—but they all contain very interesting, if sometimes horrifying, stories about America’s imperial project.

It’s difficult, even for a Filipino, not to be entertained by the descriptions in these early travelogues, revive as they do the nostalgic charm of a vanished era. Take, for example, Interesting Manila by George A. Miller, first published in Manila in 1906 by E.C. McCullough, a $10 purchase from a bookseller in Massachussetts.

Its evocation of the past reminds us that Manila was already old even then: “Beautiful these old churches were in their scars and moss and vines. Many have been spoiled by fresh coats of paint. But who can sit silent in their vaulted aisles without hearing from those stained and mellow walls, whispered prayers of priests who long since have vanished, and shadow chants of acolytes who have joined the choir invisible?… My first experience in a Manila church was at High Mass in Santo Domingo at the early hour. There were sixteen hundred candles shining in the gloom of the old sanctuary, and a thousand worshipers were kneeling on the polished floor. Among the high arches gathered the smoke of the incense, and way up in the dome the morning sun streamed red and gold through the colored glass.

“The chanting of the priests reverberated through the aisles like the noise of a cataract, and the answer of the prostrate people was like the murmur of many waters upon the sand. Then the great organ with its thundering reeds made the old pile ring and shout like some strong giant in sport, and in the succeeding silence the people waited in awe for what might follow. What did follow was the chanting of the boys’ choir without accompaniment, and the effect from the high gallery was as if the voices came from everywhere, the very stones had suddenly become vocal and joined in the acclamation.”

In a voice we might be hearing today, Miller laments the thoughtless “restoration” of these old buildings: “The present Malate church has been restored until it is of little interest. The old tile roof, the hole in the west gable made by American shot, and the walls with shrubs and trees growing in their crevices made a building worth going to see, but now it is all paint and corrugated iron.”

The vividness and vigor of the experiences described can be exhilarating: “One of the really delightful experiences that many people have never discovered is that of a trip up the Pasig at sunset. We took the car to Santa Ana and at five-thirty stood by the river and were besieged by a dozen vociferous banqueros, who contended for the distinguished honor of carrying our lunch basket to the landing. The bancas all looked alike, but there must be the preliminary diplomatic stunts as to distance and price. Tagalog, English, and bad Spanish were mixed in a verbal storm for five minutes and then we were aboard and off for Fort McKinley.”

Sometimes these colonial reports afford us a priceless glimpse into our prewar treasures, likely long gone: “There are about twelve thousand volumes on these shelves,” Miller notes of the Franciscan library. “The library of the Recoletos contains about nine thousand volumes; that of the Augustinians eleven thousand, and the Dominicans have eighteen thousand. Most of the collections contain several copies of the celebrated ‘Flora de Filipinas’ by Fr. Blanco and his co-laborers. This work is in six volumes and an index and is a remarkable piece of scientific research. The best edition contains two volumes of colored plates of the flora of the archipelago, and the press work done, in Barcelona, is of the best.”

And then again quite often the interest doesn’t come out of the narrative itself but in the perspective, which almost inevitably involves some triumphal trumpeting of America’s virtues. Miller’s assertion of the Westerner as a man of action and of the Oriental as a laidback soul is typical of these white male observers’ musings:

“The West is known by its deeds, the East by its dreams. The Anglo-Saxon lives in the concrete, the Oriental in the shadows. The American, having found a ‘proposition’ in a field, makes haste and sells all that he has and buys that field that he may dig therein and get ‘results.’ The Oriental inhales the drowsy fumes of some far-off good that was, or is, or is to come—it little matters which—and is content.”

Interesting Manila, indeed—but even more interesting was what these books said of their linen-suited writers.