Qwertyman for Monday, November 6, 2023

IT WAS probably fitting that I finished reading Patricia Evangelista’s highly acclaimed account of “murder in my country,” Some People Need Killing (Random House, 2023), over a holiday devoted to remembering the souls of the departed. I had received a pre-publication review copy from the publisher months ago under a strict embargo not to talk about it until its formal launch. As it happened, it lay under a pile of other books to be read until a flurry of posts and reviews reminded me that it was out in the open, and that the secret—not just the book, but also what it contained—could now be shared.

I can still recall the day—May 15, 2004—while we were celebrating Pahiyas in Lucban when I got the news on my phone that our representative to the English Speaking Union’s annual public speaking competition in London—a bright and pretty wisp of a teenager named Patricia Evangelista—had won the top prize. We were new to the ESU—subsequently we would produce two more global champions—and it was a grand way to announce to the world that we Filipinos could produce more than boxing heroes and beauty queens. Here was 18-year-old Patricia who could think on her feet and speak to issues of international importance, the poster child of Filipino intelligence and audacity, whose command of the English language led her to meeting no less than Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, in what amounted to a mini-coronation in recognition of her talent.

As magical as that moment was, I can only imagine how, in the months and years following, it must have begun to grate on the young Patricia to be asked to deliver her prizewinning speech in public forums over and over again, like a wind-up doll, and suffer the fate of prodigies who peak too soon. Surely that was just a beginning; surely there was more she could do—had to do—to outlive her Cinderella-like debut in London.

I would see some of that when she enrolled in my undergraduate Fiction Writing class in UP. I knew who she was and made sure to give her no special treatment—indeed to lean even a little harder on her, knowing she had what it took—but she got a “1.0” all the same, one of the few I ever gave. I can’t claim to have taught her much how to write imaginatively—her own reading had likely primed her for that—but I can’t pretend not to be proud of what she turned out to be, my pride tempered only by fatherly concern.

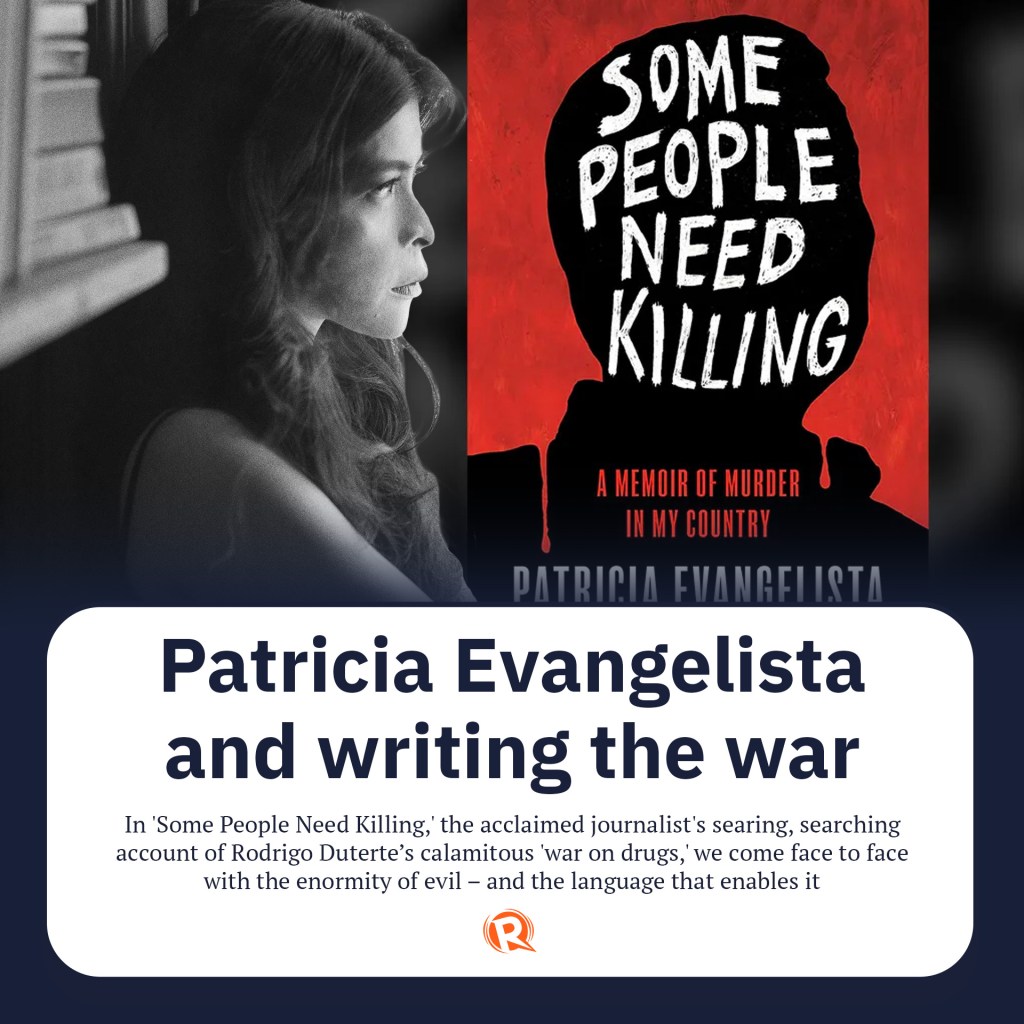

Today, almost 20 years later, the sometime ingénue returns to the global stage as a hard-bitten, chain-smoking investigative reporter—a “trauma journalist,” in her own words, very possibly one of the world’s best yet again. But there is no real prize, no princely reward, for this kind of distinction, only pain and sorrow which—subdued too many times as a matter of professional discipline—exact their toll on the body and spirit. Patricia has had to suffer that to be able to tell her story as clearly as she could, unimpeded by the hand-wringing and the preachiness that often accompany such exposés of grave misconduct.

This is not a review of the book’s explosive investigation into the thousands of extrajudicial killings that happened under the Duterte regime—that’s been done very capably by others, and is already the subject of international inquiry. The book will deserve all the journalistic accolades coming its way as an exemplar of excellent reportage.

I will not even quote from the book, as there are simply too many quotable paragraphs to choose from. Rather, I want to note, from my privileged perspective and for the benefit of younger writers, how Patricia works with language to best serve the truth. Quite apart from its journalistic merits, Some People Need Killing is one of the best textbooks out there for what we now call “creative nonfiction,” a compound of reportage, memoir, history, and fictional technique. Indeed, beyond reportage, the book is a long personal essay in which the author is inextricably part of the story, a significant step away from the impersonal and largely mythic “objectivity” that we associate with traditional journalism.

Probing murder after ghastly murder—sometimes even coming on-scene to prevent one—Patricia is both chronicler and agent, witness perhaps not to the killing itself but to the larger crime of its planning and the exoneration of its perpetrators. Handling the most sensitive and dangerous of material, she draws on more than skill to tell her story; she demonstrates raw courage, an increasingly rare quality among journalists easily seduced and silenced by pragmatism. She names names, which surely will bear consequences both ways.

I’ve often remarked in my lectures that the most endangered writers in this country are neither the poets nor the novelists, but the journalists who cannot hide behind metaphor and simile to tell the truth. We fictionists make artful lies which governments rarely have the intelligence or the patience to grapple with. Journalists live in the literal world inhabited as well by cops and crooks; what’s interesting is how the flimsy but oft-repeated fictions of “killed while resisting arrest,” so pervasive in this book, emerge from that reality.

Evangelista’s overarching technique is one of narrative restraint, informed by an English major’s awareness of how language and reality shape each other. She constantly parses the perversions of language—how words like disappear, salvage, encounter, verification, and even her own name assume different uses and meanings over time, in specific contexts. She knows—as I remind my students—that for dramatic effect, less is often more, that short sentences and blunt, single-syllable Anglo-Saxon words rather than the long, Latinate ones favored by lawyers hit closer to the gut and heart.

She is keenly aware of the power of irony—of professed liberals supporting EJK, of a morally ascendant Noynoy Aquino showing little empathy for ordinary folk, of her own journalist-grandfather affixing his signature to a petition supporting the older Marcos, and of communal complicity in the reign of terror. She uses people’s own words against them, quoting from the record. She avoids direct editorializing, or speaking in lofty generalizations like “justice” and “civil liberties,” and instead, in the best noir tradition, sees “sagging two-story tenement buildings (that) opened into dirt roads layered with garbage and last week’s rotten Happy Meal.”

After I had finished the book, I woke up at 4 am from a nightmare about running shirtless down a wet, earthen road. I was lucky. Patricia Evangelista lived through it, and I don’t even know if she’s woken up yet. Have we?

(Image from Rappler.com)