Penman for Monday, May 28, 2018

I usually reserve my weekends for truly enjoyable things, like rummaging through Japanese surplus shops or just driving down south for a hearty lunch of steaming bulalo cooled off by fresh buko juice, but there was one event a couple of Saturdays ago that I wasn’t going to miss for the world.

This was “Tirada,” the 50thanniversary retrospective show of the Association of Pinoyprintmakers (A/P, formerly known as the Philippine Association of Printmakers, or PAP) at the CCP. I recently wrote about this group when I brought up my obscure and distant past as a printmaker in the early 1970s, when I’d just stepped out of martial-law prison and was looking for something to do while I didn’t have a real job.

I turned to printmaking for a couple of years to help support myself, and those times at the PAP studio-headquarters on Jorge Bocobo Street in Ermita turned out to be one of the most instructive and wonderful periods of my life, as I immersed myself in the intricacies—and the backbreaking labors—of printmaking.

(With Pinoy printmakers Benjie Cabrera, Jess Flores, Bencab, and Egay Fernandez at the AP retrospective.)

Despite its long and glorious history, printmaking remains misunderstood and underappreciated by many. The fact that printmakers will often make multiple copies of the same work seems to debase the value of the work in the eyes of art buyers looking for something totally unique, like an oil painting. But printmaking’s great contribution to art was precisely its democratization, by making art accessible to many, beginning with the engravings that illustrated old books and newspapers and lent visual credence to literature and journalism. Prints also adorned books on anatomy, horticulture, geography, and astronomy, among others, without which science could not have progressed.

It was an imaginative step to move from the print as functional appendage to the print as an art form in itself, and many artists took that step because it offered a fascinating alternative, with its own fresh challenges, to the sometimes staid art of painting. Prints require a heavily physical and tactile engagement with one’s tools and materials, like sculpture, working with plates, inks, papers, and presses.

Back in the PAP days—employing techniques that hadn’t changed much since Durer and Rembrandt used them centuries ago—we drew designs on zinc plates coated with an asphalt “ground,” soaked them in nitric acid which ate away the designs, cleaned and inked the plates, then rolled them onto paper under enormous pressures to produce etchings. (Today printmakers use polymer plates, not metal—a technique I’ve yet to learn, not having touched a burin or engraver’s tool in over 40 years. The Japanese, of course, used wood, and others use linoleum and stone for their material.)

The PAP was formed in 1968, led by such pioneers as Manuel Rodriguez, Sr. By the time I found my way to Jorge Bocobo five years later, its regulars included the likes of Orly Castillo, Manolito Mayo, Fil de la Cruz, Jess Flores, Joel Soliven, Rhoda Recto, Petite Calaguas, Benjie Cabrera, Fernando Modesto, Bing del Rosario, and Emet Valente. Some days I’d watch Bencab and Tiny Nuyda at work, or just listen to their banter, which was just as valuable to the salingpusaI was, eager for a whiff of the artistic life (I would become a full-time writer a few years down the road).

Some of those stalwarts have since passed on, but seeing their works on display at the CCP—alongside a whole new generation of brilliant Filipino printmakers—revived happy memories of the kind of camaraderie that AP leader and master printmaker Pandy Aviado referred to in his remarks. Painting can be a lonely art, and perhaps it needs to be, but printmaking typically attracts the collective assistance of others, as physically strenuous as the work can get.

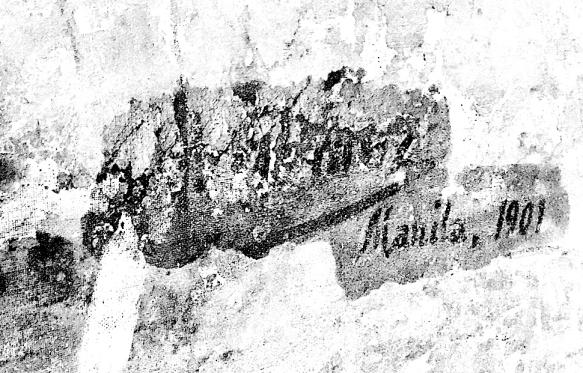

My solitary contribution to the show—a 1975 etching of my grandmother—proudly hung beside one of Bencab’s in the corridor outside the main gallery, but I felt happiest just to share the company of old friends from another branch of the arts that I’d stepped away from, perhaps too quickly. I remembered the sheer exhilaration of lifting the dampened paper off a pressed plate to see one’s design in vivid ink, a joy tempered but also deepened by the intensity of filing away and smoothing out the rough edges of a zinc plate, or inhaling a vinegary cloud of acid, or pouring cold lacquer thinner onto one’s fingers to wash away the grime.

“I wish we had a small etching press at home,” I found myself telling Beng—only to be told by a new acquaintance, the artist Angela Silva, that the renowned Raul Isidro had one, or a few, to sell, having commissioned a raft of them to help spread the faith. I made a beeline for Raul, and then and there reserved myself a unit, with Beng’s blessings.

I’ve decided to return to printmaking in the most old-fashioned way with a technique called drypoint, scratching out my designs with a sharp tool by hand on a copper plate. I can just see how busy my retirement’s going to be a year hence—and how messy. But what a marvelous mess I hope to make.

(With artist Raul Isidro, receiving my baby press. The print above is Joel Soliven’s “Owl70” from my collection.)