Penman for Monday, August 31, 2020

FEW OF us might have noticed, but one of the casualties of the Internet age has been the magazine as we knew it—the general-interest magazine, which usually came out on weekends, often as a newspaper supplement. With the decline in print-media readership and the depredations on economic and social life brought on by the coronavirus, magazines around the world have been shutting down, although of course that decline long preceded Covid. Some survive in vestigial form, or have gone online, but are nowhere near the familiar and colorful periodicals you couldn’t wait to pull out of the Sunday paper.

People my age still remember the Sunday Times Magazine, the Asia Magazine, the Mirror Magazine, and others of their kind—including, of course, the old standalone Free Press and Weekly Graphic magazines. Unlike the specialized glossies of later decades, they had something for everybody, weren’t just trying to sell you something, allotted several pages for serious literature, and were worth saving and passing along. I spent many an hour in the barbershops of Pasig thumbing through the Free Press and imbibing Nick Joaquin’s reportage on crime and politics while trying to figure out the poetry (too abstruse for my Hardy-Boys years) and gawking at the lifestyles of the rich and famous in the society and entertainment pages.

With martial law and its aftermath, everything became either overtly political or seemingly in denial of anything gone wrong. The age of gadgets was upon us, and we devoured magazines devoted to the minutest differences between July’s and August’s cellular phone. The pretty ladies remained on the cover, of course, but largely as purveyors of dresses or some other thing; the innocence was gone—or perhaps we had simply lost ours in the interim.

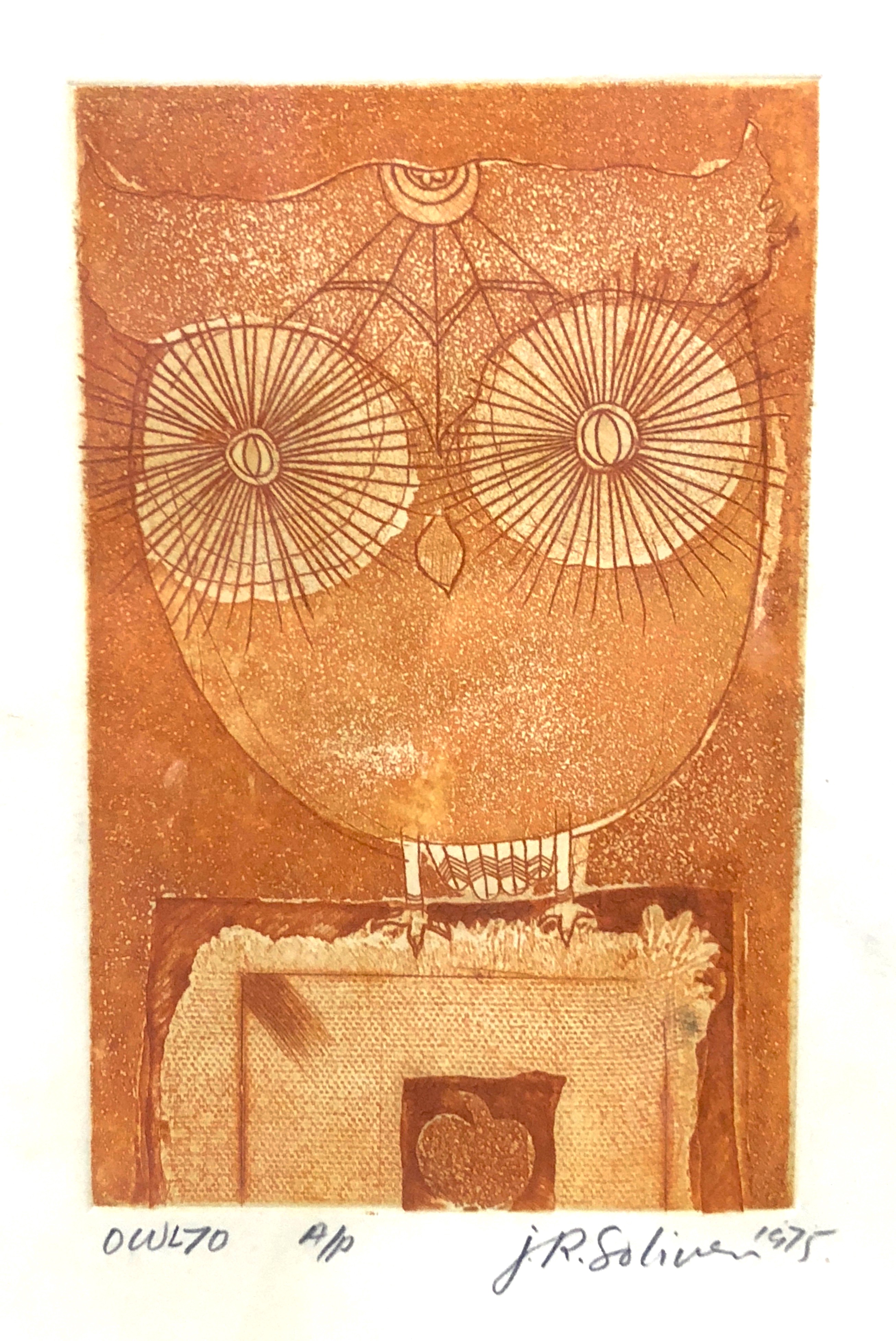

My interest in magazines became a bit more professional in graduate school when my professor in Bibliography, an old-school gentleman named Dr. Kuist, told us that he had done his dissertation on The Gentleman’s Magazine, said to be the first publication to call itself a “magazine” (from the French for “storehouse”) in 1731. Despite its title, it was no girlie mag, and contained a gamut of articles of interest to everyone (a copy I have from November 1773 features an ad for “The Frugal Housewife, or Complete Woman Cook” and articles on “Arguments in Favour of Rolling-Carriages” and “Description of a Machine for Making Experiments on Air”).

Many years ago, sometime in the early 1990s, when my passion for all things vintage began to be awakened, I spotted an ad in the Classifieds of a newspaper offering a stash of prewar magazines for a reasonable sum, and I drove off in my VW Beetle to a corner of San Juan to retrieve them—three or four milk-can boxes of them, all yellowed and crumbling—from a family that would have thrown them away otherwise. They were mainly copies of the Sunday Tribune Magazine from the 1930s, and some copies of the Sunday Times Magazine from a bit later.

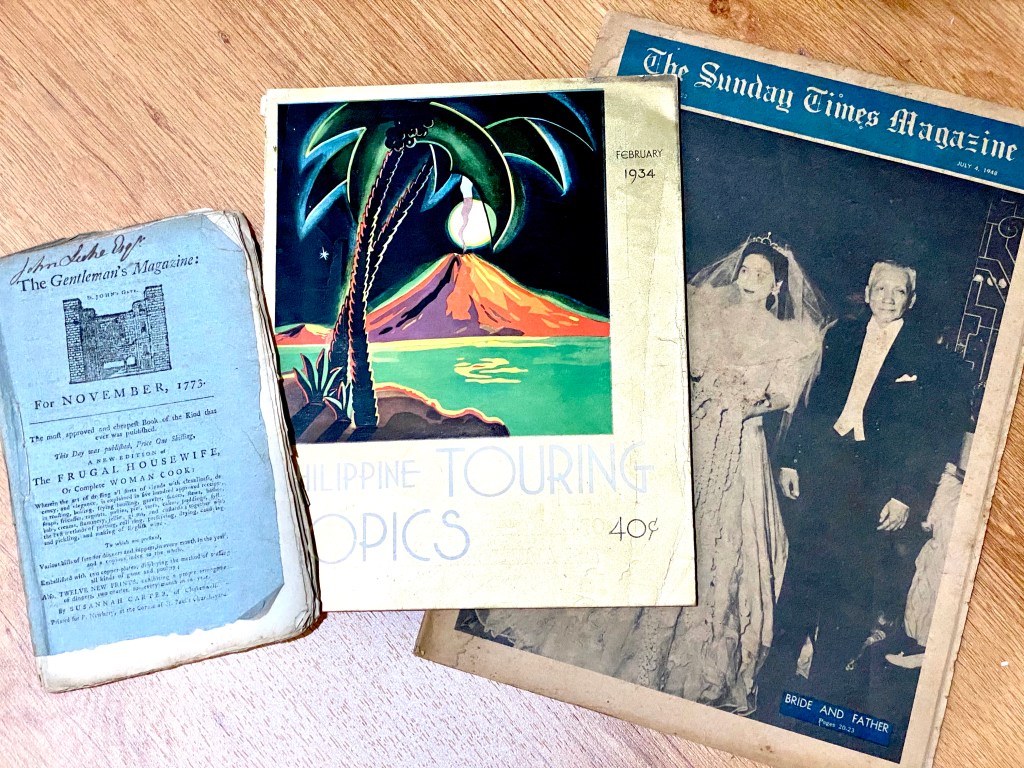

I continued to add to what had become a de facto collection—copies of the prewar Philippine Magazine and Philippine Touring Topics, among others, as well as issues of Tagalog periodicals like Lipang Kalabaw and even a 1911 issue of La Cultura Filipina. I used to put copies of these on my coffee table when I had an office in UP, to surprise and amuse my visitors with—sorry, folks, don’t have the November issue of the Tatler yet, but here’s a travel mag from 1934.

Make that February 1934, when Philippine Touring Topics contained—like most good magazines of the time—a combination of substantial articles, classy advertisements, and a gorgeous Art-Deco cover. Featured were articles on Igorot folklore, Mindanao fashions, Philippine hardwoods, the gypsies of the Sulu Sea, Philippine tobacco, a voyage from Manila to Bali, and celebrity travelers. (As usual, it was the ads I found most fascinating—for the American President Lines, the 1934 Studebaker, and Alhambra cigars.)

My greatest reward in flipping through these yellowed pages is discovering things I never knew about—things not too remote to be ancient history. In my July 4, 1948 issue of the Sunday Times Magazine, for example, is an article on the winners of that year’s Art Association of the Philippines painting competition. The top prize of P1,000 went to the “basketball-crazy” Carlos Francisco (who, says the anonymously catty commentator, is also “an amateur, not-so-good photographer, avid for picnic photos”); P750 for second prize went to Demetrio Diego; P500 for third prize went to Vicente Manansala “by a nose” over the P250 fourth prize to Cesar Legaspi; two honorable mentions—good enough for artists’ materials—went to the stragglers Diosdado Lorenzo and H. R. Ocampo. Elsewhere in the issue is an article on the all-but-forgotten winner of a 1946 contest for the Philippine Independence Hymn, won by a composition of Restie Umali. On the cover is a radiant Rosie Osmeña, being walked down the aisle by her dad the former President, with an accompanying spread on her wedding trousseau.

What’s not to like? When the Internet goes down—and someday it just might—these magazines with their pictures might just be our best chronicle of life and of the Philippines BC (Before Covid).