Penman for Sunday, January 7, 2024

FEW WILL remember this, but one of the very first things I wrote about when I began this column for the STAR back in mid-2000 was my passion for leather. By that I mean good, well-crafted leather briefcases, bags, watch straps, and such accessories beloved of both men and women seeking a timeless alternative to today’s synthetics. There’s still nothing like leather to suggest authenticity, tradition, pedigree, and care—care because it requires skillful crafting as well as devoted maintenance by its user.

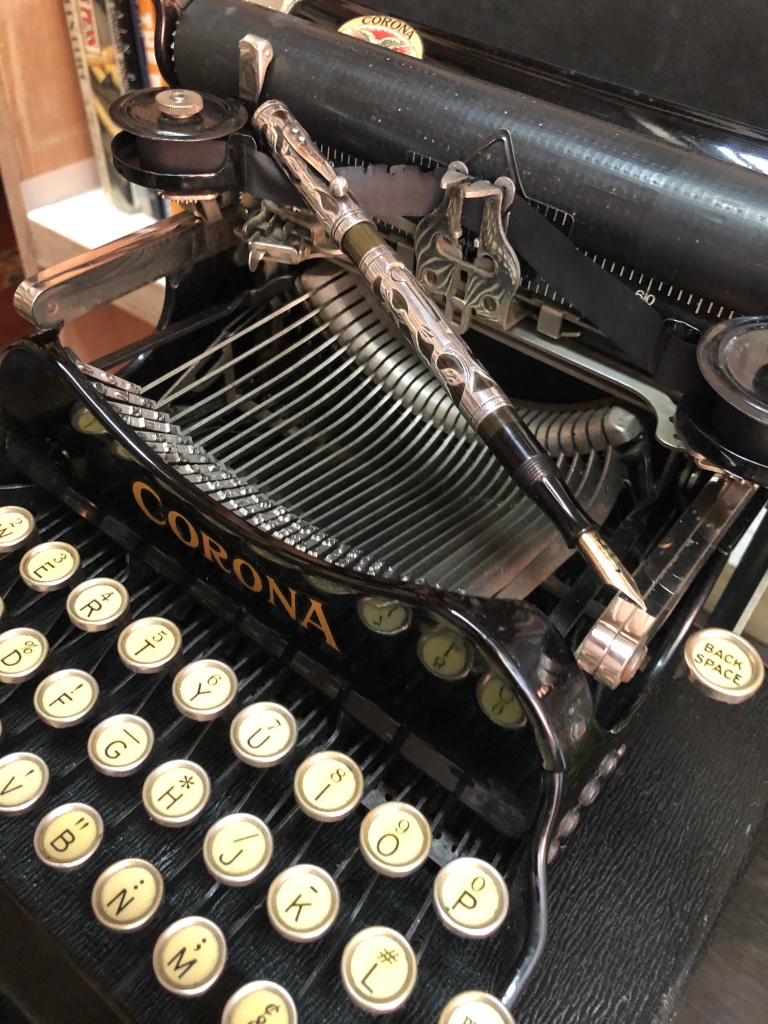

All these came to mind when I first met Raymund Nino Bumatay, who goes by the trade name “Amon Ginoo,” at the Manila Pen Show last March, where he introduced his Leather Luxe line of luxury pen cases. At my age, and having seen quite a bit of what’s out there, I’m a difficult man to please, but Amon’s work ticked all the boxes (except perhaps one—affordability, which we’ll get to later), particularly the quality and craftsmanship that connoisseurs demand. He catered to a highly specialized clientele, so I wanted to know how he could merge art and business and succeed on both counts.

Amon was engaged in graphic design and marketing when the pandemic hit, hitting his profession badly. Over the long lockdowns, he began thinking of ways to both express himself creatively and make some money. That was when the idea of making leather cases for fountain pens came to him, spurred on by instructional YouTube videos. Why pens?

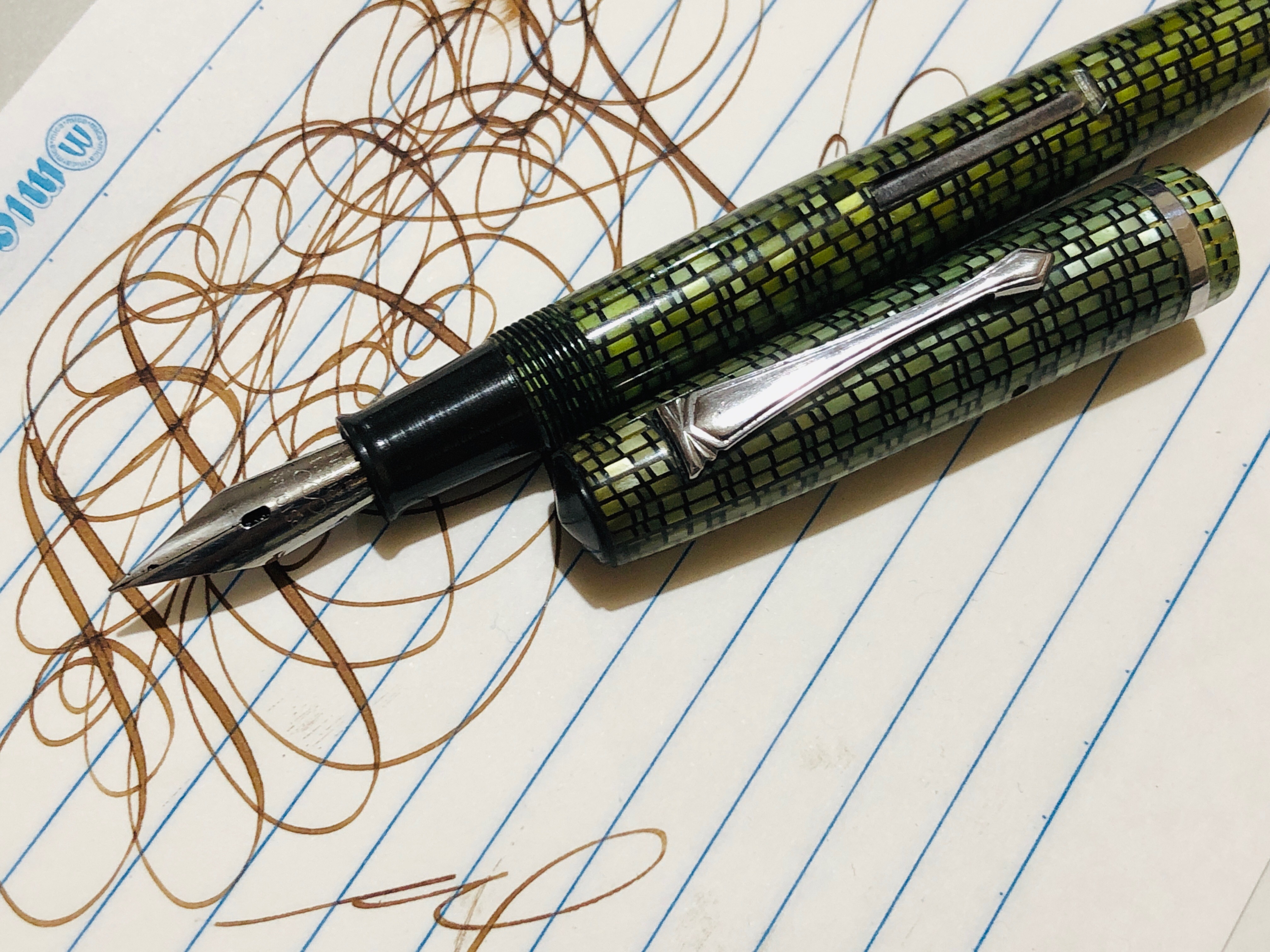

“I have been a fountain pen enthusiast since 2015,” Amon told me. “I started out with a simple and reliable Lamy Safari that’s still with me, and while journaling and writing were a common pastime during the lockdowns of 2020, I yearned to make something by hand that would house my humble fountain pen collection. This was why the very first and noteworthy leathercraft that I successfully completed was a fountain pen case.”

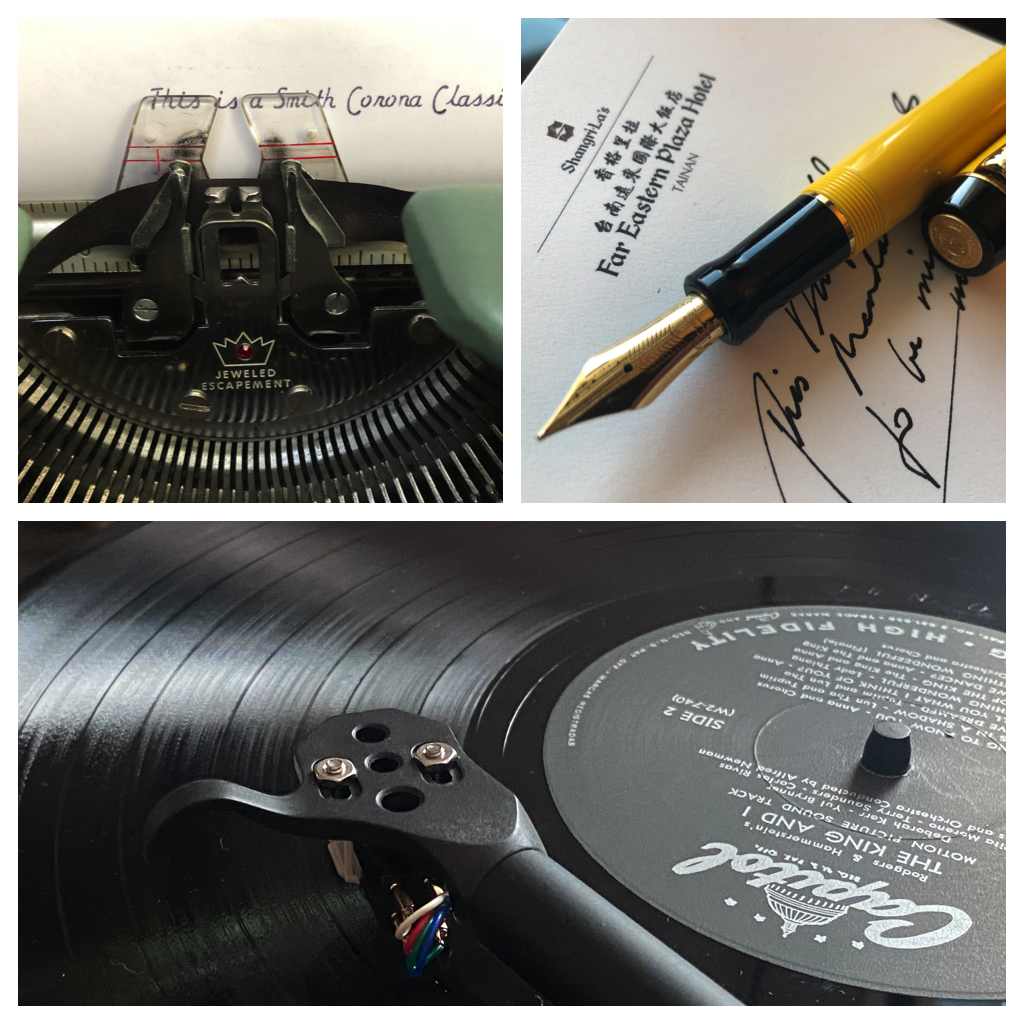

Amon, it must be said, is but one of a new generation of fountain pen collectors and users, among whom Filipinos now rank among the world’s largest and most enthusiastic communities. The Fountain Pen Network-Philippines (FPN-P), which I helped found in 2008, began with 20 members but now counts more than 13,000 in its Facebook group, most of them successful young professionals between 30 and 45, along with more senior CEOs, Cabinet undersecretaries, topnotch lawyers and doctors, and aging professors like me.

This was Amon’s ready-made market. Most people will do with just one pen that they’ll typically clip into their breast pocket or toss into a bag, but for fanatical collectors who amass hundreds of pens and carry a dozen of them around to pen meets, good cases are de rigueur. For everyday use, a three-pen leather case is normal.

Amon wouldn’t be alone in supplying this market. Aside from imports, some other local artisans have been making quality pen cases. But Amon’s are on a whole other level, employing the choicest leather and featuring exquisite and even bespoke designs, which account for their premium pricing. His cases are, to put it plainly, truly world-class.

First, of course, he had to learn his craft. “After making a couple of leather fountain pen cases with one of my daughters, my wife asked what I was planning to do with all those prototypes. I explained that those were just practice pieces that I wanted to perfect and play around with. She insisted that I sell them so I could make this venture sustainable. My wife urged me to start branding these handmade pieces, saying they would serve as great homes for the pen collections of other enthusiasts. It took me a year and a half to muster the courage to finally put a brand to the craft I started and to begin offering my goods to FPN-P members. Thus was LeatherLuxePh born.”

He was soon spending long hours trying out new methods and designs, aside from amassing leathercrafting tools from around the region and from Europe. And then there was the key aspect of the leather itself. “When I was just starting, I got my leather from Marikina, but when things began to get serious, I had to resort to Italian and French leather, sourced from distributors in Singapore, South Korea, and Hong Kong. I’ve also sourced leather from Brazil and Indonesia.” Aside from top-grade hides, he also uses exotic leathers such as snakeskin, ostrich, and stingray. “Each pen case is meticulously handcrafted, handstitched, and assembled by hand. The hand stitching alone needs a calm and steady hand, but I find it relaxing. We have spared no expense in choosing the best leathers, tools and supplies available and continually reach out to our clients to be able to share in their experience and further improve on what we have started.”

Amon found a receptive audience among FPN-P’s advanced collectors, whose five- or even six-figure Montblancs and Nakayas couldn’t just be carried around in pedestrian plastic or cardboard boxes. Among Amon’s repeat clients is CEO Jun Castro, who says that “I need a pen case for my big pens. Normal size pen cases would not fit them or be too tight to easily take them out.” Amon, who is based in Baguio, would even come down to work with clients to make sure he meets their very specific needs.

Of course, I had to ask Amon if he planned to expand LeatherLuxePh’s line beyond fountain pen cases, given the narrow niche it occupies. Yes, he says—but not too far from his base that he would compromise quality. “I’ve noticed that most Pinoy leathercrafters flock to bags, wallets, belts, and the like. New entrants usually resort to pricing that tends to undermine the artisan side of the craft. We decided to focus on pen cases precisely because very few of us do it. But we’ll venture into related items such as leather covers for journals and even a traveler’s kit for fountain pen enthusiasts. We’ll also tap the international fountain pen market this 2024 as a proud Pinoy brand.”

The upcoming 2024 Manila Pen Show on March 16-17 should be the perfect venue for LeatherLuxePh’s new products and designs. Can’t wait to see what this artist in leather comes up with next! (Meanwhile, check out LeatherLuxePh on FB and IG.)