Qwertyman for Monday, January 22, 2024

THERE WAS a lot of snickering around the local Internet a couple of weeks ago when the University of the Philippines announced that it was going to offer a course on the American megastar Taylor Swift. “Why???” seemed to be the most common hair-trigger response, expressing consternation over the need or rationale for such a course. “This is where your taxes go,” lamented another netizen.

The clear suggestion was that spending a semester—that’s 16 weeks—on a pop phenomenon like Taylor Swift was a grandiose and frivolous waste of teaching time and people’s money, scarce resources better allocated to studying worthier topics like, say, Gomburza, the South China Sea, endemic species, and sovereign wealth funds. (Not incidentally, all these other topics are already covered in other UP courses, so no one need worry that they’re being sacrificed for in-depth analyses of “Cruel Summer” or “You Need to Calm Down.”)

Before we go any further, I have to declare that I’m no Swiftie, as her adoring fans call themselves, and I had to look up and listen to those two titles I just mentioned. At my age, my idea of a diva I’d pay good money to listen to is Barbra Streisand, Laura Fygi, Lisa Ono, and Dionne Warwick, none of them below 60. I have to admit that the only Swift song I was aware of before she exploded into global stardom was “You Belong with Me,” which my then-teener niece Eia used to bounce her head to (an effect that, I’ve since discovered, many Swift pieces tend to induce).

Still, my instinctive reaction to the announcement of the UP Swift course wasn’t “Why?” but what I suppose is the academic’s default of “Why not?” When I looked into how the course was going to be taught by its instructor—Cherish Aileen Brillon, a mass communications specialist who had previously published a paper on, among others, “Darna and Intellectual Property Rights”—I could see that this wasn’t going to be just party time for 15 kids listening through Taylor Swift’s ten albums (yes, I counted) over a semester, but serious study connecting material from the singer’s songs and of course from her life as a 21st century celebrity to our reception of her and whatever she represents, as Filipinos.

The course—an elective under the BA Broadcast and Media Studies program of the Colle of Mass Communication—will focus on “the conception, construction, and the performance of Taylor Swift as a celebrity and how she can be used to explain our and, of course, media’s relationship with class, politics, gender, race, and fantasies of success and mobility…. Gender should be part of the discussion because Taylor is a woman operating in a highly patriarchal and misogynist entertainment industry,” Brillon told the STAR in an earlier interview. “Transnationality is also a large part of the discussion,” she added, defining the term as a “media-driven flow of goods, products and services from various nations” in this globalized age. “Celebrities have always been transnational anyway. The class will look into the transnationality of Taylor and how Filipinos are appropriating their relationships with celebrities.”

If you know anything about what’s being taken up in universities worldwide today as media and cultural studies, that mouthful I quoted above is heavy-duty academic work of the kind I myself may not be too keen to undertake, but the results of which I’d be deeply interested to find out. And that because there’s nothing more pervasive and influential in our world today than the media, which includes the Internet, TV, radio, and newspapers, plus all the advertising, the tweets, the Facebook feeds, the Spotify music, and the Amazons, Lazadas, Shopees, and eBays you find in them. How the media draws our attention and often subliminally persuades us into buying certain products and ideas can’t be worthier of academic research and investigation.

And it’s not as if this hasn’t been done before. New York University, Stanford, Arizona State University, the Berklee College of Music, Rice University, UC Berkeley, the University of Florida, the University of Delaware, and Brigham Young University are among the American universities offering Taylor Swift courses from different approaches ranging from the music itself to social psychology, marketing, and literature.

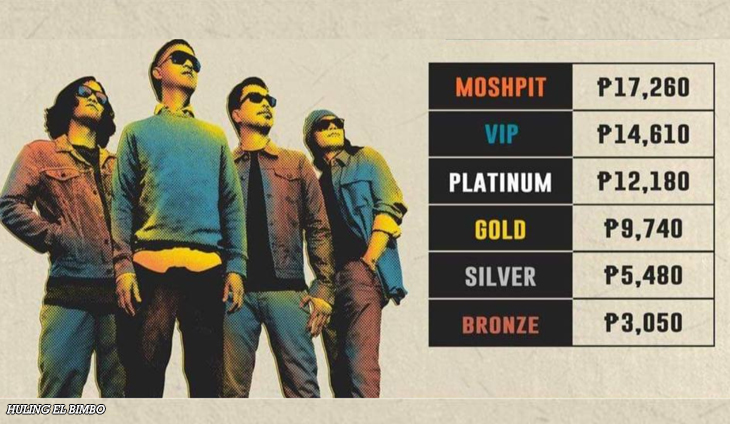

So, okay, they’re Americans—why us Filipinos? Because the singer has a huge Pinoy fan base, despite the slight that local Swifties felt when she left the Philippines out of her 2024 Southeast Asian “Eras” tour, for which well-heeled Pinoys then rushed online to book expensive ticket packages for her shows in Singapore. (She’s been here twice before, in 2011 and 2014.)

But never mind Taylor Swift. Back in 1995, scholars attending the first International Conference on Elvis Presley at the University of Mississippi’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture got academia “all shook up,” according to reports, with papers bearing titles like “A Revolutionary Sexual Personae: Elvis Presley and the Acquiescence of Black Rhythms,” which discussed sensuality and spirituality in Elvis’s acts.

And then, of course, there are all the college courses on Frank Sinatra at Suffolk University, and on the Beatles at MIT and Oxford, among many other places. At Carnegie Mellon University, flautist and Prof. Stephen Schultz alternates teaching 18th-century Baroque music with a class on the Beatles; guess which class attracts 200 students a semester.

I’m sure that, despite these precedents and rationales, there will remain many skeptics who’ll still believe that all this academic mumbo-jumbo is just an excuse for both professor and student to kill an hour and a half doing nothing but nodding their heads to pop tunes and chatting about which song’s lyrics were cooler. (Don’t be too surprised, but that’s also basically what happens when we discuss poetry and fiction, sans the rhythmic nodding.)

But then you could be talking about Taylor Swift and her songs—or you could be talking about how Adolf Hitler and his deadly message were packaged and sold to the German people, not to mention Donald Trump and other despots closer to our time and place. This is what media and cultural studies are ultimately about—the power of media and other cultural forces to shape our minds, our purchases, our votes, and therefore our history.

Perhaps our students can even learn more from a semester of Taylor Swift, BTS, and Justin Bieber than the Shakespeare they’ll merely turn to AI to write papers on. Like I told one naysayer, “We keep studying history, religion, law, etc., and yet we seem to learn nothing—just look at how a former human rights lawyer suddenly justifies EJKs.” So there may yet be more to Taylor Swift 101 than meets the eye. As another Swift—Jonathan—put it, “Vision is the art of seeing what is invisible to others.”

(Image from Sky News)