Qwertyman for Monday, June 5, 2023

I HAVE a good friend whom we’ll call Ted, a Fil-Am who retired a few years ago as a ranking officer in the US Navy. He was in town recently on some family business, and like we always do when circumstances permit, we had dinner and a good chat just before he and his wife flew back home.

Most of us have friends if not relatives in America, and all of this would be pretty routine except for one fact: I’m a flaming liberal, and Ted is a Trump Republican. Over the fifteen years or so that we’ve known each other—well before Donald Trump entered the picture—we’ve been aware of those political differences, but rather than politely skirt them in our conversation like many sane people would, we feel comfortable enough with each other to talk at length about them, and even exchange some friendly barbs.

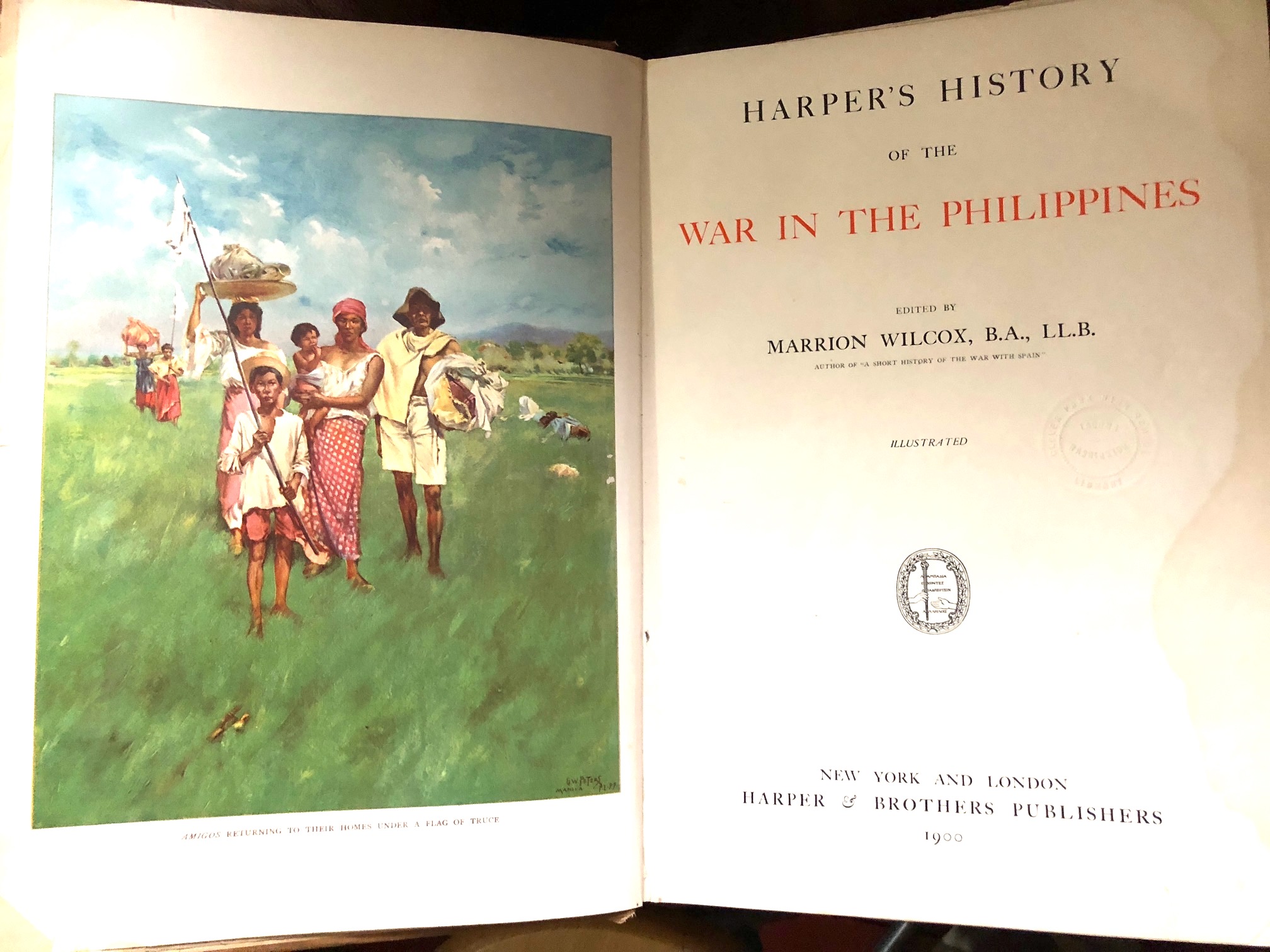

Much of that level of comfort comes from my belief that, in his own way, Ted sincerely and deeply loves his country—and his ancestral home, the Philippines. He’s smart, curious, eager to learn and understand. In his former naval job and as a private citizen, Ted—who was born in the US but spent some of his formative years in his family’s hometown in Bicol, and speaks some of the local language aside from Filipino—has visited the Philippines as often as he can, trying his best to improve relations between the two countries on a personal level. (On this last visit, for example, he also took part in a ceremony to celebrate the commissioning of the USS Telesforo Trinidad, named after an Aklan-born Filipino petty officer who was awarded the Medal of Honor for bravely rescuing his shipmates from an explosion aboard their ship in 1915.)

Given his naval background—his dad joined the Navy in the 1970s—I’m not surprised that Ted is a Republican, like many military Fil-Ams are. (One notable exception is a mutual friend of ours, the former West Pointer, Army Ranger, and diplomat Sonny Busa, as staunch a Democrat as they come, and a key figure behind Filipino veterans’ causes in Washington.) His support for Trump despite the man’s many failings continues to mystify me, but I’m guessing that in his calculations, Ted chose to cast his lot with the man best positioned to thwart the liberal agenda. That includes items that Ted and other Republicans feel extremely uncomfortable with, such as what he calls the “celebration, beyond just acceptance” of transgender rights, and their judicial enforcement.

Perhaps with any other person, my liberal hair-trigger would have fired away at such comments with a fusillade of counter-arguments, but with Ted I find more value in listening and trying to understand a certain mindset, as different as some of its premises may be from mine. In our last conversation, what Ted had to say was profoundly disturbing. I’m paraphrasing here, but essentially it was this: “America is a mess. People can’t talk civilly to each other anymore. When I say I’m a Republican, people instantly assume I’m a racist.” To which I said that people at the top like Trump (and our own version of him here) greenlighted that kind of boorish discourse, with additional pressure brought on by right-wing militias armed with AR-15s. We talked about January 6 (which he opined was not an insurrection) and the Second Amendment (which I said seemed sacrosanct in American politics). “You have cancel culture,” he sighed, “to which the other guy responds by going bam bam bam!” He was deploring, not endorsing it, trying to get a fix on his own society’s ailments. “It’s in our DNA,” he said glumly about guns.

Thankfully Ted and I always have other things to talk about—like the Philippines, in which Ted said he feels much more relaxed than his own country. He knows how worked up I can get about politics and our own leadership (or the lack thereof), but as far as he could see on this trip, I and my fellow Filipinos (including those he met in Bicol) were just chugging along. “We’re survivors,” I said, “and we’ll do what it takes to get by from day to day.”

That brings me to another friend, “Tony,” who messaged me out of the blue the other day, obviously distraught by the Senate vote on the Maharlika Fund bill and asking if it was time for him and his family to leave the country, given how we seem to be back on the road to political plunder and economic ruin. It wasn’t just a rhetorical question; he was really thinking about it. Here’s what I said:

“Hi, Tony—If it’s a realistic option, I don’t think anyone can or should blame you for leaving or wanting to leave. We have only one life and we have to make the most of it in all ways. Politics is important, but it’s only one of many other factors that define who we are—love, art, family, and faith, among others. That said, it can have a way of complicating our lives and life choices.

“Moving to the US has also been an option for me for some time now. Our only daughter lives in California and has been wanting to petition us. But my wife and I have been strongly reluctant to move there, although we visit almost every year and are familiar and comfortable with living in the US, where I spent five years as a grad student. We are artists, and our work is culture-bound. We feel appreciated here, within our small circle of friends. However good we may be, in America we would be marginalized; we don’t want to become an American minority and deal with all the issues that will come with it. And America has become much less inviting now, with all the intolerance and racial violence provoked by Trumpism.

“So unless it were a matter of life and death, we’ll stay here, despite the present dispensation and many more aggravations like the Maharlika Fund to come in the years ahead, because I feel that my continued survival and success will be my best way of fighting back. Having survived martial law, we can survive this as well. Everyone’s circumstances are different, and again you should feel free to find your place where you can best live with your family and secure their future. Nothing is ever final anyway, and you can always come back. Follow your heart and conscience, and you should be all right, wherever you may go. All best!”

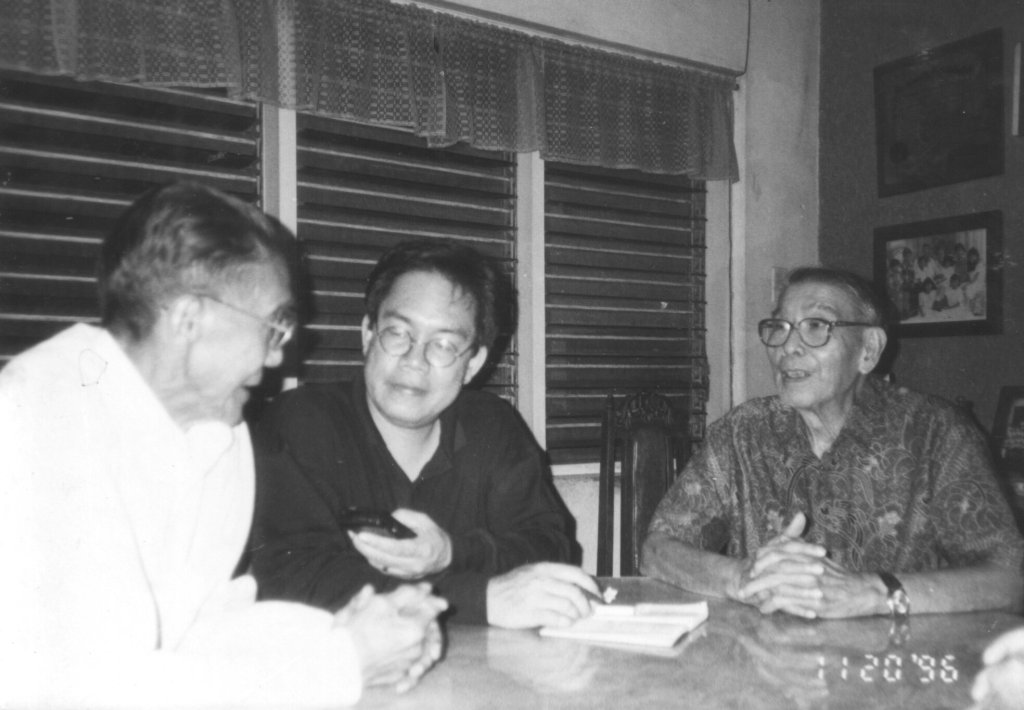

(Image from bu.edu)