Hindsight for Monday, April 18, 2022

ONE OF the most troubling episodes of the war now raging in Ukraine happened a couple of weeks ago not in Kyiv or the eastern region—where ghastly atrocities have taken place—but in Penza, a city in western Russia. A 55-year-old teacher named Irina Gen was arrested after a student reportedly taped her remarks criticizing the Russian invasion; the student’s parents got the tape, and turned it in to the authorities, who went after Ms. Gen. She now faces up to ten years in prison for violating the newly minted law against “spreading fake news” about Russia. Earlier, in the city of Korsakov, students also filmed their English teacher Marina Dubrova, 57, for denouncing the war; she was arrested, fined, and disciplined.

That the Russian state is punishing its critics is nothing new. It’s reprehensible, but you expect nothing less from the place and the party that invented the gulag, that frozen desert of concentration camps where millions suffered and died over decades of political strife and repression, mainly under Joseph Stalin.

What I found particularly alarming was the role of students as informants, a virtual extension of the secret police that are the staple of repressive societies. This, too, is nothing new. Throughout modern history, despots have drawn on their nations’ youth to lend a semblance of energy and idealism to their authoritarianism, ensure a steady stream of cadres, and at worst, provide ample cannon fodder.

In Russia, the Komsomol rose up in 1918 to prepare people between 14 and 28 for membership in the Communist Party. Four years later, the Young Pioneers took in members between 9 and 14, and just to make sure no one who could walk and talk was left out, the Little Octobrists were organized in 1923 for the 7-9 crowd.

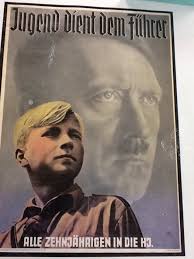

The Hitler Youth was preceded and prepared for by youth organizations that formed around themes like religion and traditional politics, and it was easy to reorient them toward Nazism. An all-male organization matched by the League of German Girls, the Hitler Youth focused on sports, military training, and political indoctrination, but they soon had to go far beyond marching in the streets and smashing Jewish storefronts. Running short of men, the Germans set up a division composed of Hitler Youth members 17 years and under, the 12th SS-Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. It went into battle for the first time on D-Day in June 1944; after a month, it had lost 60 percent of its strength to death and injury.

Chairman Mao relied on China’s teenage cadres—the Red Guards—to unleash the Cultural Revolution in 1966 against the so-called “Four Olds” (old customs, culture, habits, and ideas, which came to be personified in elderly scholars and teachers who were beaten to death or sent off to prison camps for “re-education”).

Under Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s martial law, the Kabataang Barangay was created by Presidential Decree 684 in 1975 to give the Filipino youth “a definite role and affording them ample opportunity to express their views.” That sounds innocuous enough, and indeed the KB would go on to engage in skills training, sports, sanitation, food production, crime prevention, and disaster relief, among other civic concerns, under the leadership of presidential daughter Imee.

At the same time it was clearly designed to offset leftist youth organizations like the Kabataang Makabayan and the Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan by drawing on the same membership pool and diverting their energies elsewhere—more specifically, into becoming the bearers and defenders of the New Society’s notions. (Full disclosure: I was an SDK member, but my younger siblings were KB.)

I would never have thought that the “Duterte Youth” meant something else, but it does; evidently, it’s just shorthand for “Duty to Energize the Republic through the Enlightenment of the Youth Sectoral Party-list Organization.” Organized in 2016 to support the Davao mayor’s presidential campaign and later his policies as President, the Duterte Youth have affected quasi-military black uniforms and fist salutes. Its leader, Ronald Cardema, reportedly brushed off comparisons with the Hitler Youth by pointing out that the Germans had no patent on the “youth” name, which he was therefore free to use. (Uhmm… okay.)

Adjudged too old to represent the youth in Congress (his wife Ducielle took over his slot), Cardema was appointed to head the National Youth Commission instead, from which perch he then directed “all pro-government youth leaders of our country… to report to the National Youth Commission all government scholars who are known in your area as anti-government youth leaders allied with the leftist CPP-NPA-NDF.”

I acknowledge how Pollyannish it would be to expect young people and even children to be shielded from the harsh and often cruel realities of today’s world. The war in Ukraine, the Taliban in Afghanistan, and the pandemic are just the latest iterations of conflicts and crises that have turned 12-year-old boys into executioners in Sierra Leone and child miners in Bolivia, Madagascar, and, yes, the Philippines.

Their enlistment in political causes—of whatever orientation—is another form of maltreatment or abuse for which we have yet no name, but few governments or anti-government rebels will let them be. Their minds are soft and malleable, their fears obvious and manipulable, their rewards simple and cheap. With the right incentives and punishments, it can be easier to turn them into monsters or machines than to safeguard their innocence. They can be weaponized.

I’ve mentioned this in another column, but there’s a scene in the classic movie Cabaret, set in the Nazi period, where a handsome and bright-faced boy in a brown uniform begins to sing what seems to be an uplifting song about “the sun on the meadow.” But as it progresses we realize that it’s a fascist anthem which is picked up by ordinary folk with chilling alacrity. Watch this on Youtube (“Tomorrow Belongs to Me”) and then look at your son or nephew, or the children playing across the street. If you want, you could vote to have them marching and singing a similar tune in a couple of years.