Penman for Monday, September 27, 2021

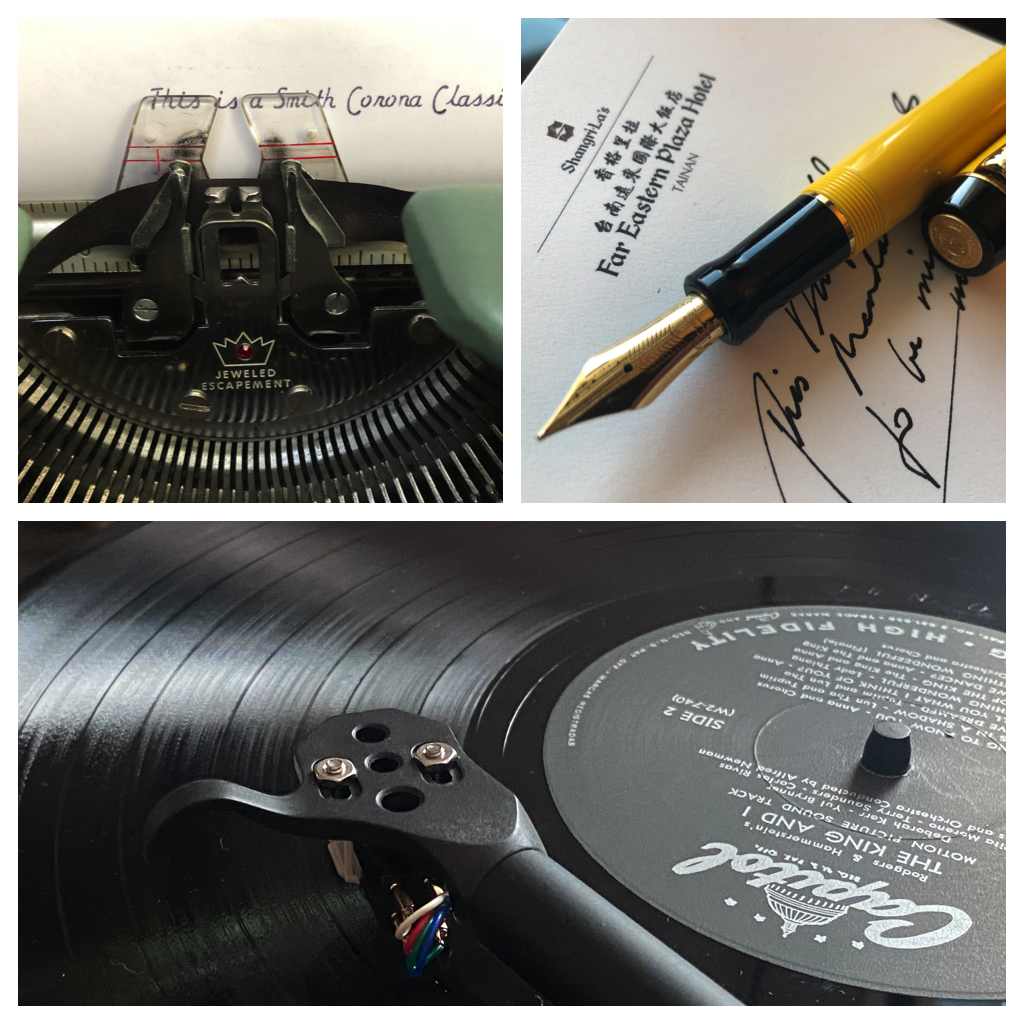

TWO YEARS ago, just before the Covid pandemic turned the world upside down, another and much less noticed reversal took place. Ending a 33-year trend, vinyl records outsold CDs—1.24 million records toting up $224 million in global sales, according to Music Times. You’d think that grandparents the world over had launched a conspiracy to buy out the remaining stock of Mantovani, The Lettermen, and the Ray Conniff Singers, but no—70 percent of the buyers were millennials under 35.

Audiophile Eric Teel says that “Music lovers have long treated vinyl with a kind of mysticism, using terminology like ‘warmth’ to describe a special intangible quality that some say eludes digital recording technology. Getting the most out of a vinyl record requires more effort than the simple huff of warm breath and a wipe on the t-shirt that many of us (shouldn’t, but do) give a CD to wipe off fingerprints before sticking it in a player.” In other words, there’s the sound, and there’s the ritual of choosing, cleaning, and playing the record—all before putting one’s feet up on a stool and sipping coffee.

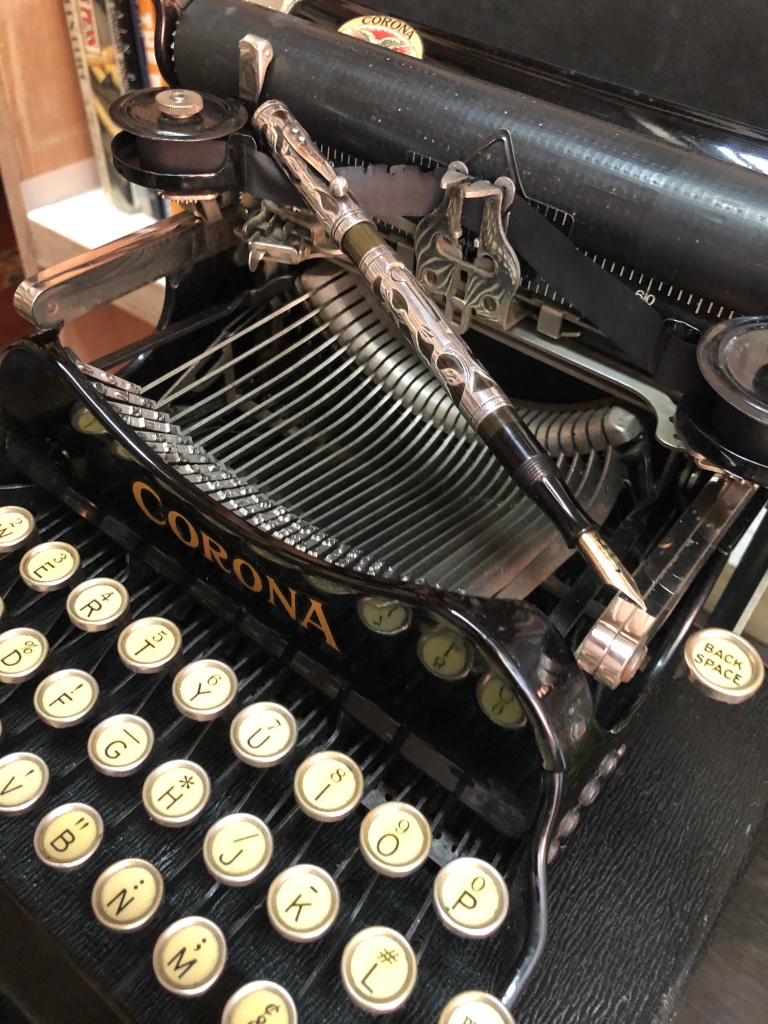

Even earlier, in 2014, someone named Alex Lenkei wrote an essay on medium.com about another kind of hole he had fallen into—manual typewriters. Explaining why he found his way back to typewriters in the age of the Internet, Alex said:

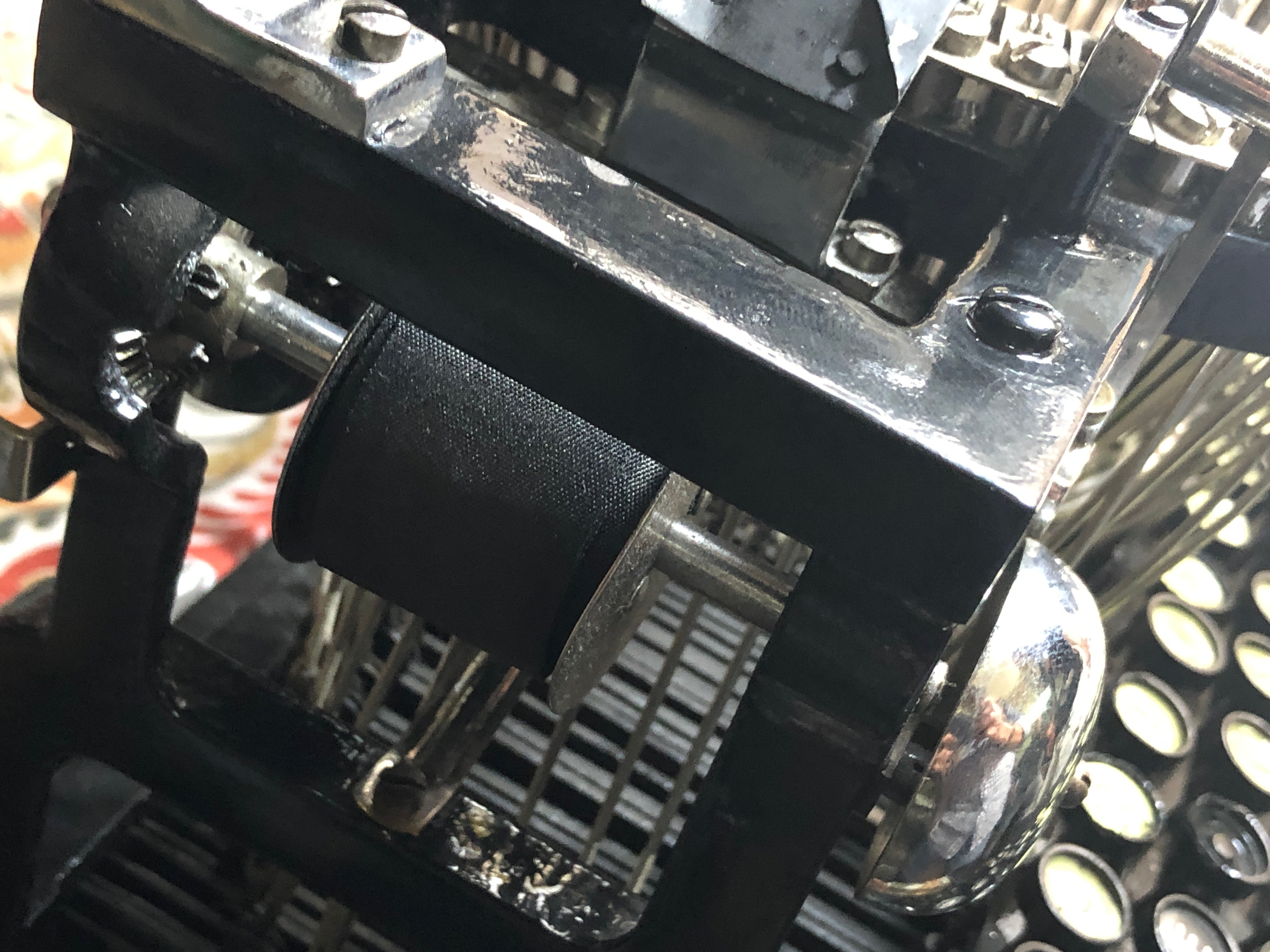

“Like people, no two typewriters are the same. Each one feels distinctly different and has a different history of grade school assignments, covert love letters, prose and poetry, government propaganda, and wartime memos. The coldness of the keys under your fingers feels like the only truth in the world and the smell of metal and grease when you dig your nose into the typebars, the cavity of the machine, feels like the home of a serious writer.

“A typewriter is a miraculous tool for disconnecting in a time when we are all constantly connected to our smartphones or tablets. When I’m sitting down at a computer, I don’t know what I’m going to do next; I can get distracted very easily. In today’s increasingly connected world, production and focus in writing are being sacrificed for Facebook updates, tweets, and blog posts. There are a thousand distractions. But with a typewriter, I know I’m writing.”

The third analog instrument that’s made a comeback is—you guessed it—the fountain pen. According to the Washington Post, “In the 1990s, high-end, limited-edition pens took off…. The recession of 2008 dried up the ink on those for a while. The current fountain pen revival, penfolk agree, has been driven by an unlikely group: millennials. Yes, a generation that wasn’t taught cursive and whose members do most of their writing on a keyboard or smartphone screen has breathed new life into the old-fashioned fountain pen.

“’There’s less writing now, but when they do write, they want a good experience….’ That means premium pen, nice paper, unusual ink—stuff that looks good on Instagram…. A lot of the pens are used for keeping something called a dot journal or a bullet journal, which is basically a fancy to-do list.”

It’s obvious from these testimonials what’s been happening, aside from the fact of genuine oldtimers like me hanging on to their tools and toys: a whole new generation has reached far into the past for a new experience unavailable in the digital world—something tactile, something hands-on, something requiring more personal investment than a keystroke or tapping on “Play.”

That’s nowhere more evident than in our local pen fanciers group, Fountain Pen Network-Philippines (fpn-p.org), which since its establishment in 2008 now counts over 11,000 members online. I’d say at least 70 percent of active members are below 40. The group’s original focus was fountain pen collecting, especially vintage pens, and old guys like me were happy just to ogle our pen-filled boxes and occasionally write some lines with black or blue-black Quink.

Our newest and younger members are clearly more excited by swatching colorful inks that shimmer and sheen, by learning calligraphy and journaling, and by just getting together as a community to enjoy a newfound passion. In other words, it’s not so much the object but the experience that matters most, asserting oneself in a digitized universe.

I also help moderate the Filipino Typewriter Collectors group on FB, and we’ve passed more than 1,000 members in less than a year. As with pens, most of our members are young, artistically inclined, expressive, and fascinated by using old tech to do 21st-century tasks. Again, I’m the crusty hardware guy who appreciates the machines as artifacts (having written books with them ages ago), while our newbies can still be thrilled by the clatter of keys on a platen and by the words they can form on a blank sheet of paper.

I grew up with vinyl, but came relatively late to the collecting party. We have a small, private Viber group that exchanges tips on where to find certain LPs cheap. We’re not learned enough to consider ourselves audiophiles fussing over “curve” and “coloration”; we just want to relive our youth by listening to the Beatles, Brasil ’66, and Marianne Faithfull. What’s surprising is, we have some teenage members who are discovering this music for the first time on vinyl, and liking it. Suddenly, their lolos and titos are cool again. There’s hope for the future yet!