Qwertyman for Monday, July 31, 2023

BECAUSE OF a glitch that happened when Chinese hackers tried to hijack America’s C-Span network so they could replace congressional programming with X-rated cartoons (on the theory that no one would miss the analogy), for a few minutes in the early morning of July 24, 2023 (Eastern Standard Time), the channel’s viewers were treated instead to the live coverage of an apparently big event happening in faraway Philippines.

Celebrities and bigwigs were getting dropped off by their limousines and luxury SUVs at some place called the “Batasan,” which a commentator helpfully explained was the building that housed the Congress of the Philippines—the Philippine Capitol, in other words, minus the dome.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy was just about to go to bed in his home in Bakersfield—he had flown back to California for the weekend to avoid the screechings of the Freedom Caucus in his ears—and he had been having a hard time sleeping, wondering which was worse, having to deal with Joe Biden or with Donald Trump. Just when he was about to drift off to dreamland, his cellphone rang. It was an aide back in Washington, and immediately Speaker Kevin wondered if something earthshaking had happened—like Biden resigning after being diagnosed with dementia or Trump discovering honesty and humility and turning to God. “Boss, you have to see this. Tune in to C-Span!”

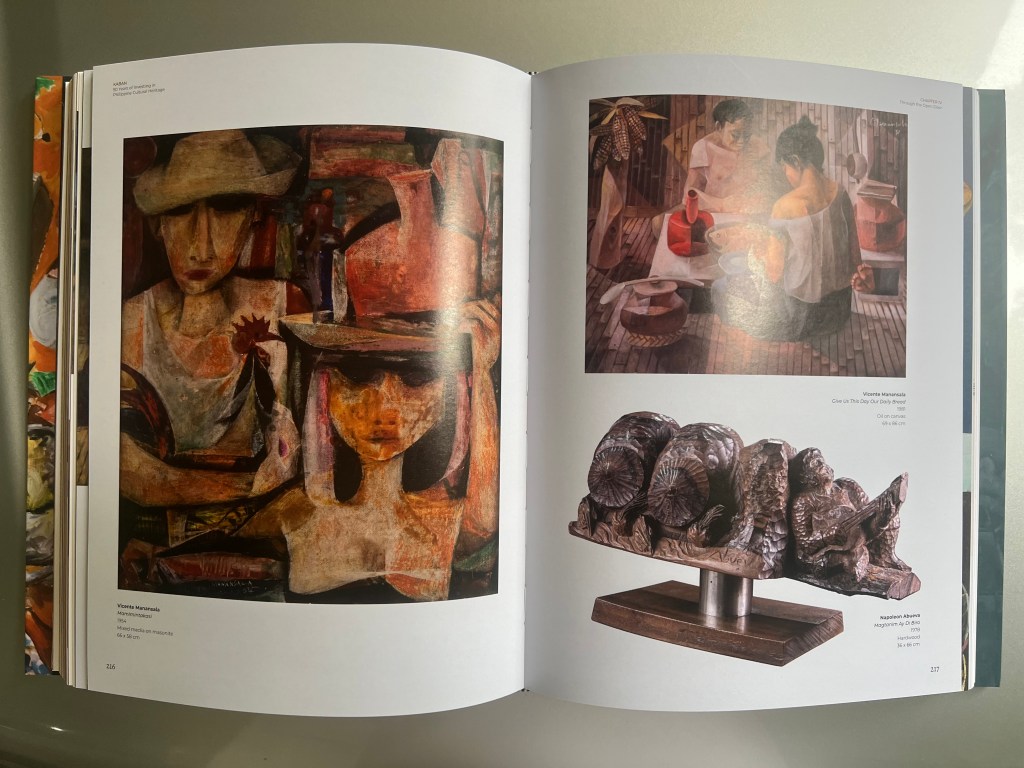

Grumbling, the Speaker did as asked and had to rub his eyes as he watched a woman step out onto the red carpet dressed like some aboriginal priestess, complete with warlike tattoos. Others came in headdresses, butterfly sleeves, heavily embroidered gowns, and sashes with pictures of dead people. “What’s going on? What the hell am I looking at? Is this some movie premiere or what?”

“It’s a live feed from the Philippines, what they call a SONA—the president’s State of the Nation Address, their version of our State of the Union. The president’s arriving shortly to deliver his speech.”

“You woke me up to get me to listen to some political crap in some backwater country? Are you out of your mind? Don’t we get enough of this in DC?”

“No, no, boss, it’s not about the speech—that’s the whole point, forget the speech, it’s about the fashions! Look at them, preening like peacocks and peahens. Look at the coverage, I’ll bet you, tomorrow, all the papers and social media in Manila will be talking about the dresses, not the speech!”

“And so?” Kevin got up from bed, sufficiently intrigued to pour himself a scotch in anticipation of a longer chat. This aide was his top PR strategist, and sometimes the guy came up with truly inspired ideas, like plucking Ms. Horseface away from the Freedom Caucus to boost his conservative credentials and keep the restless natives in check. Joe Biden was the enemy, but his own crew members could be a bigger pain.

“Well, don’t you see, boss? Joe Biden’s next SOTU is coming up, and… we need a distraction. We don’t want him lecturing the American people about how we’re stripping women of their rights to safe abortions, or teaching the young that slavery had some real benefits, or carving up congressional districts to make sure that dark-skinned people don’t get too much sun on election day. I mean, he’ll do that anyway, but these Filipinos know something we don’t—it’s not the speech, it’s the party! We can turn the SOTU into a fashion show and no one will care what Old Joe says!”

McCarthy took a closer look at the screen and listened to the commentators blabbering about this and that gown and comparing it to last year’s versions—the more outrageous, the better. He recalled being canceled back in January for appearing in a picture wearing a blue suit with brown shoes—par for the course in cool Europe but never in redneck America!—and smiled in anticipation of his revenge.

As it turned out, the Speaker and his aide weren’t alone. Before the footage could be pulled off C-Span, it had made the rounds of the bars around Washington, DC, and someone found even more detailed coverage on YouTube, and when daylight broke over the Potomac it was all that the senators, congressmen, and their flunkies could talk about over their morning coffee.

“So what are you going to wear to the SOTU?” reporters asked Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene as soon as she stepped out the door of her DC apartment. She had a ready answer for that, having pondered the question over her Wheaties: “I’ll come in a long black dress,” she said, “with the word IMPEACH running down the front!”

It didn’t take long for Marjorie’s arch-rival on the right, Rep. Lauren Broebert of Colorado, to announce that she was coming “As Annie Oakley, in defense of the Second Amendment, the biggest victim of all the mass shootings happening in America today!”

Even Kari Lake, who was still refusing to accept her defeat for the governorship of Arizona, revealed that she was attending the SOTU as a guest, and that she was coming dressed as a Mexican muchacha—“Not to glorify diversity or any of that woke garbage, but to draw attention to illegal immigration, which is sucking the lifeblood of this great country and its legal, blue-passport-carrying citizens!”

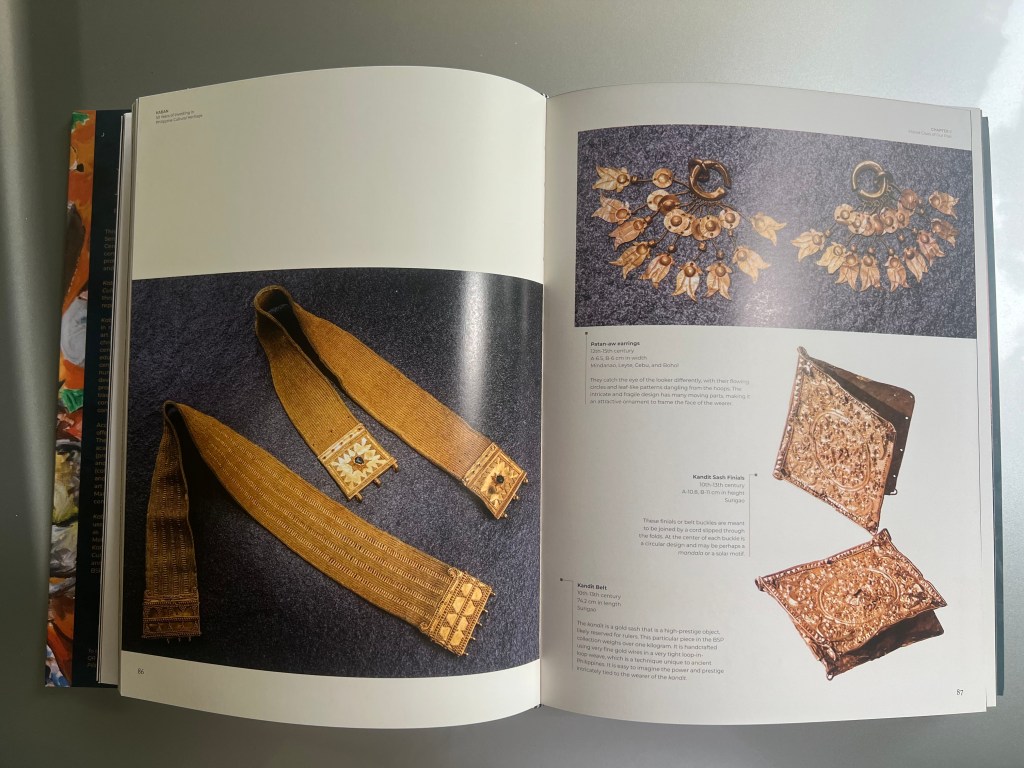

Sen. Tommy Tuberville of Alabama, who had stubbornly and singlehandedly been holding up the confirmation of dozens of generals because he didn’t want the military to pay for the abortions of women in the service, had his own idea: “I’m having myself fitted for the uniform of a Confederate general.” Inspired by something he had seen on a related YouTube clip, he added, “And for good measure, my wife Suzanne will be wearing a gold necklace made from the excavated medals and buttons of Union Army officers!”

Reached for comment at Mar-a-Lago, Donald Trump declared he wasn’t coming, and fumed when a reporter reminded him that former presidents were invited to the event. “Who’re you calling a former president? That thievin’, lyin’ Joe is a never president—never, never, never! I should be the one giving the SOTU, not him—and I will, again!”

Alerted to the SONA brouhaha by his butler, Joe Biden passed the sugar on to Jill as the video played in the background. He listened briefly to the other president’s speech and smiled. “A New Philippines, hmmm…. How does ‘A New America’ sound to you, honey?”

“I think not,” said Jill. “In fact, we rather miss the old one, don’t we? When America was a kinder and gentler place?”

“That’s George Bush Senior’s line, honey. From the 1988 GOP convention.”

“Exactly. Back when even some Republicans got some things right.”