HAVING SOME fun with my Conway Stewart Marlborough and sepia ink that I mixed myself.

HAVING SOME fun with my Conway Stewart Marlborough and sepia ink that I mixed myself.

Category Archives: Pens

Penman No. 104: The Psychology of Collecting

Penman for Monday, July 7, 2014

Penman for Monday, July 7, 2014

EVERY OTHER month or so, I take the 200+ contents of my fountain pen collection out of their wooden boxes and leather cases—a few of which reside in a fireproof safe—to ink, doodle with, clean, and reorganize. It’s a ritual that invariably leaves me pleased and at peace. Sometimes I reorganize the pens by age, sometimes by maker, sometimes by color or material.

Any serious collector of, well, seriously anything will recognize this behavior. And I do mean anything—I’ve met people who collect not just the usual stamps or coins or even watches and cars but barbed wire and tractor seats. (I met the tractor-seat fellow 25 years ago in a barn full of antiques in Ohio; when I expressed astonishment at his specialty, he turned around and said, with scholarly disdain at my ignorance, “There’s a fanny for every seat!”)

In the pen forums I inhabit, there’s a never-ending discussion about being either a “user” or a “collector,” the implication being that collectors are simply moneyed hoarders while users are simple, practical-minded folk who’ve never forgotten what things are for. I propose that the truth, as it often does, lies somewhere in between; many users are wannabe collectors, and most collectors have never stopped being users. It’s pointless to think of, say, a 1925 Waterman Sheraton or a 1934 Wahl Eversharp Doric as being just a pen you can write with, like a cheap ballpoint; they may have been utilitarian tools once, but somewhere along the way they crossed the line and became jewelry and art object.

At least that’s how I excuse amassing and periodically gloating over, say, my dozens of Parker Vacumatics, a 1930s-40s pen that forms the core of my collection. This was the pen I wrote my 1994 short story “Penmanship” about. (It’s a story about a story that I’ve often told, but the sum of it is that I found this 1938 Vacumatic Oversize in a pen shop in Edinburgh, paid a month’s salary for it, suffered buyer’s remorse, then decided to write a story about the pen, which won first prize in a contest that made me back my salary.) I know enough about Vacs that I can put you to sleep by mumbling mantras such as “Vac nomenclature covers a fascinating maze of models and colors—the Junior, the Major, the Standard, the Slender, the Debutante, the Oversize, the Senior, which is not to be confused with the Senior Maxima, since the Senior came out only in 1936….”

About 15 years ago it wasn’t pens but laptops—yes, Apple Macintosh Powerbooks, particularly the Duo line (the granddaddy of the MacBook Air and all those super-slim laptops people toss into their briefcases today). I had (and still have) about a dozen of these machines, which I used to take apart to upgrade the memory and hard drive (back when 240 megabytes made you king of the hill), before putting them back together again and then pressing the power button to hear that unmistakable startup chime that told me I had done everything right, so I could then step out and face the world and slay dragons and then sign memos.

So why do otherwise presumably sane people like me get our kicks by amassing strange objects most other people wouldn’t give a second look or drag into their homes even if you paid them to do it? I asked myself this question again last week as I changed out the inks (another ritual for the devotee) in my glorified Bics. Why do we take them out week after week, not to write a novel or a draft SONA but endless iterations of “I love this pen I love this pen”?

First of all, you want to be reassured that they’re still there. Collectibles have a way of walking away on little cat feet, and collectors have a sixth sense about what’s missing from the picture.

Second, you want to reassure yourself that you know why they’re there—that the objects have some aesthetic and monetary value. Perhaps that value’s known only to a very few people, which is not a bad thing, because it’s proof of your connoisseurship, of a certain esoteric form of expertise that’s taken you some time and expense to cultivate. It’s like getting a PhD in the truly little, truly fun things (and what’s a PhD these days except a lot of knowledge about very small things, hardly any of which is fun?).

You may be a total loser in nearly every other aspect of life—your face could resemble a well-worn shoe, your family may have deserted you for the coldest parts of Canada, your car could be an escapee from the junkyard—but if you know everything about tourbillons, carburetors, calibers, and (in my case) nibs, then you have good reason to face the world with pride if not arrogance; you have, after all, one of the world’s largest collection of GI Joes, or Tonkas, or Ken dolls, or whatever floats you boat.

Third, let’s go online and ask the experts. Dr. Mark McKinley, in a much-quoted piece on “The Psychology of Collecting” in The National Psychologist, goes back in time to note that “During the 1700s and 1800s there were aristocratic collectors, the landed gentry, who roamed the world in search of fossils, shells, zoological specimens, works of art and books. The collected artifacts were then kept in special rooms (‘cabinets of curiosities’) for safekeeping and private viewing. A ‘cabinet’ was, in part, a symbolic display of the collector’s power and wealth. It was these collectors who established the first museums in Europe, and to a lesser extent in America.”

Since I’m sure I don’t collect Sheaffers and Esterbrooks to show off my power and wealth, let’s see what M. Farouk Radwan (who holds an M. Sc., so who presumably knows what he’s talking about) says about the subject: “Since early years human beings used to collect food in order to feel safe and secure. Because acquiring food was a difficult process with uncertain outcomes humans learned to ease their anxieties by storing the food they needed. The same need, which is to feel secure, is the primary motivating force behind the creation of collections.

“Because life is uncertain and can easily make a person feel helpless some people use their collections to create a private comfort zone that they can control. By arranging and disarranging their collections compulsive hoarders can regain the sense of control over their lives. These actions reduce anxiety and helps those people cope with the uncertainty of the real world.”

So we go back to basic needs and instincts: food and security. McKinley puts these together: “For some, the satisfaction comes from experimenting with arranging, re-arranging, and classifying parts of a-big-world-out-there, which can serve as a means of control to elicit a comfort zone in one’s life, e.g., calming fears, erasing insecurity. The motives are not mutually exclusive, as certainly many motives can combine to create a collector—one does not eat just because of hunger.”

That’s a brilliant insight—“one does not eat just because of hunger”—and it leads to my favorite explanation of the psychology of collecting, propounded by Robert and Michele Root-Bernstein (co-authors of Sparks of Genius, the 13 Thinking Tools of the World’s Most Creative People) in “The Collection Connection to Creativity” (Psychology Today, May 2011):

“The fact is collecting exercises a number of important mental tools necessary for creative thinking. The collector learns to observe acutely, to make fine distinctions and comparisons, to recognize patterns within her collection. These patterns include not only the elements that make up the collection, but the gaps in it as well. Learning how to perceive what isn’t there is as important as knowing what is! And the collector also knows the surprise of finding something that doesn’t fit the collection pattern: Is the mismatch a fake? An exception? Something that belongs in another collection? Broken patterns are often the ones that teach us the most by challenging our preconceptions and expectations.”

Patterns, designs, mismatches, aberrations: early in 1937, just for a few months, Parker came out with a special Vacumatic, with the word “Vacumatic” etched in the gold-filled cap band. It’s one of the holy grails of Parker collectors, one of the rarest and most expensive of finds, and I have one. That should make it the crown jewel of my collection, but it isn’t; it’s the pen that made me write a story about it that’s the rarest one of all, that gives me a lifelong excuse for picking up tubes that squirt inks.

(If you like pens, join us at Fountain Pen Network-Philippines, www.fpn-p.org. We’re marking our sixth anniversary this week!)

Flotsam & Jetsam No. 36: Dandy Doodle

THIS IS what I do to relax–doodle all day with my pens and inks.

Penman No. 89: Camels and Scribes

Penman for Monday, March 17, 2014

Penman for Monday, March 17, 2014

A FEW months ago, I wrote about the fountain pens that famous people like T. S. Eliot, Winston Churchill, and Neil Gaiman used, and especially about how Eliot’s pen had been donated by his widow Valerie to the Royal Society of Literature for members to sign themselves with into the society’s logbook. The more practical-minded will and should, of course, dismiss any such discussions of celebrity memorabilia as mere fetishism, an adoration of idle and otherwise meaningless objects.

Happily, that’s a charge I can live with, as an incorrigible collector of lovable old junk, particularly pens to which I’m drawn by some deep Freudian current I won’t even try to palpate. I never even excuse the fact that I collect pens not so much to write as to doodle with—I enjoy laying wet bright lines on a crisp sheet of paper and watching the ink spread and shade. Whatever words I may be forming really mean little; it’s the sheer pleasure of forming the words that matters for the moment, the joy of the first pictographer tracing the outline of a bull on a cave wall, of the medieval scribe illuminating the Book of Genesis.

Eliot and Co. weren’t collecting Watermans and Conway Stewarts, of course; they were putting them to work. In their time, everyone wielded a pen, from insurance executives like Wallace Stevens to ambulance drivers like Ernest Hemingway and Walt Disney. Soldiers carried pens with them to the trenches, using ink pellets they could dilute in water; today these wartime pens and their embedded pellets are highly prized.

I was thinking of just this scene last week when I came across a thread in a pen forum talking about the pen or pens that T. E. Lawrence—Lawrence of Arabia, immortalized by Peter O’Toole in the 1962 film epic—used in his desert campaigns. Lawrence was an indefatigable writer, and his Seven Pillars of Wisdom remains as interesting today as when he published it in 1922.

The forum discussion wasn’t really even about Lawrence’s pen but the ink he used; apparently, he preferred a special French-made ink, one that his pen could safely ingest and expel. India or carbon ink is fine for drawing but is usually too thick for use with conventional fountain pens, whose feeds or ink channels it will clog. A forum member (many thanks to “carlos.q” from Puerto Rico) had dug up a typewritten letter from Lawrence, who was back in Southampton, dated May 3, 1934 and addressed to a friend initialed “FV”. In it, he complains (note his curious abuse of the colon) that “I apologize for the ink. The only carbon ink that will run in a fountain pen is Bourgeois: and that is sold only by Reeve in the bottom of Charing Cross Road. I have emptied my bottle of all but the too-thick dregs: I cannot demand more by post: but as soon as the R.A.F. will pay my expenses to London for a working day I shall go to the shop and buy some, and again charge the excellent pen. Only carbon ink is ink—that I wholly agree. I badly want to reach London again, but cannot afford a private visit.” (It’s sad enough to see this proud man in such dire straits, but sadder still to know that he would be dead in a year, from a motorcycle spill.)

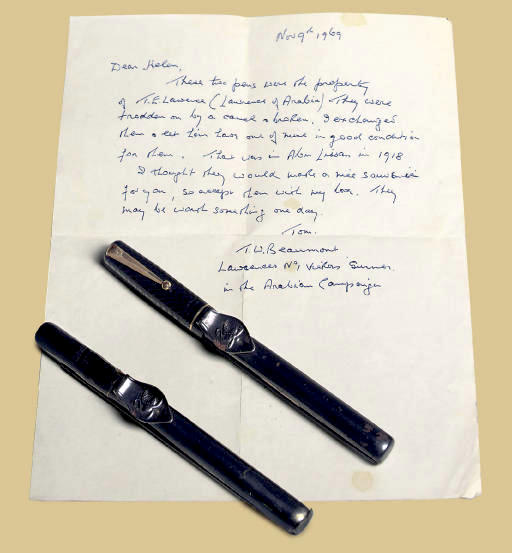

Lawrence’s pen—two of them, actually, a Swan and a Conway Stewart—would turn up in a Christie’s auction in 2007, realizing over $5,000. The pens were accompanied by a 1969 letter from a Lawrence associate establishing their provenance, which noted that they had both been “trodden on by a camel & broken,” although this likely applied only to the Swan, as the Conway Stewart pictured had been made much later than Lawrence’s camel-riding days. The letter does end, presciently: “They may be worth something one day.”

That’s something we all wish we could say for our possessions, hopefully without requiring the chunky foot of a roving dromedary to enhance their narrative value. Having just stepped into the gray zone of seniorhood, I often wonder what will become of my trove of mostly vintage Parkers, Sheaffers, Montblancs, Pelikans and what-not once I sign my last signature. They’ll be worth something, for sure, but all of them put together might not even be enough to trade up for a Rolex, so it isn’t their bankable value I’m thinking about, but the stories they carry, especially the dozen or so in my daily rotation: “This one I got from the Thistle Pen Shop in Edinburgh, and it led to a story that became a book; this one I found in the Greenhills tiangge, selling for a tiny fraction of its actual worth; this one was being sold by a shop in Auckland, but it was missing a tiny part, a tassie which I later found online at the Berliner shop in New York; this one I found in an antique shop on Morato, inscribed to a ‘Consuelo,’ who would have worn it as a pendant on a chain….” And so on.

Last year I told myself that I would try to unload about a third of the collection, thinking to keep just the best dozen or so by the time I turn 70, but turning 60 gave me an excuse to acquire even more ink-spitting baubles. How to say no to a half-priced Montblanc Oscar Wilde, the flamboyant companion to my black-and-formal Agatha Christie? Or the Onoto Magna Classic in mottled tortoiseshell, its golden tongue spinning tales in a summery green-gold (known to ink connoisseurs as Rohrer & Klingner Alt-Goldgrun)? Let me declare this here and now: camels are strictly forbidden from entering my barangay in UP Diliman; any large humpbacked mammal coming within a hundred meters of my house will be shot on sight (with liberal squirts of india ink).

Now, if all this talk of bygone pen-mongering strikes a responsive chord in you—evoking the inner Lawrence or the inner Agatha (Christie tracked Lawrence’s footsteps in Syria, intrigued by his spying)—you might want to pay a visit to the newest pen palace in town, a veritable emporium of pens, papers, inks, and even wax seals.

The members of our local (and still growing on its sixth year!) pen club, the Fountain Pen Network-Philippines, were a captive crowd at the recent launch of Scribe’s new flagship store at the East Wing of Shangri-La Plaza Mall. Scribe’s owner, the lovely and gracious Marian Yu-Ong, recalled how the business began in 2002 as an importer of writing and reading products, before opening its first store in Eastwood Mall in 2009. Also featured at the launch were the works of three master calligraphers whom Scribe has designated its ambassadors: hand-lettering maven Fozzy Dayrit, advertising executive Leigh Reyes, and architect-conservator Mico Manalo.

Today, if you want to feast your eyes on the largest and most sumptuous range of quality pens, papers, and inks in Metro Manila, there’s really no other place to go but Scribe Writing Essentials—make that “places,” because aside from Shang and Eastwood, Scribe can also be found at Glorietta 5, SM Aura Premier, and SM Megamall Fashion Hall.

I paid a visit to Scribe’s new flagship store after the launch, and was impressed to find an assortment of quality pens that we used to have to order online or fly to Hong Kong, KL, or Singapore for, and at very competitive prices, brands like Pelikan, Sailor, Platinum, Kaweco, and TWSBI, as well as the more familiar Cross and Lamy.

Here’s my standing advice to fountain-pen newbies, faced with these choices: if you want one good, classic pen you can expect to use for the next ten years, invest in a Pelikan; if you want a good, well-designed pen with a great nib for a price that won’t break the bank, try the Taiwan-made TWSBI (twis-bee), a huge hit among pen aficionados. Then treat yourself to a bottle of J. Herbin ink and a Midori notebook, and before long you’ll be scanning the horizon for wayward camels.

(Upper photo from christies.com)

Penman No. 84: Pens & Inks

Penman for Monday, February 3, 2014

A YEAR ago, I wrote a piece for this column titled “The (ink and) paper chase,” where I talked about how obsessed some people get with finding just the right paper to write on, fussing over paper color, texture, thickness, and (important to us fountain pen users) feathering and bleed-through.

The last two factors have to do with how tightly the paper’s fibers are packed; the looser they are, the easier it is for ink to spread and scatter through the paper—not a good thing if you’re trying to write a legible letter. This is why ballpoints and cheap paper make better partners—and a good thing, too, that they do, because most people have neither the time, the inclination, nor the loose change to play around with fancy pens and papers, let alone exotic inks.

But what if you did?

In that column last year, I promised I would write a bit more about inks—the essential, indispensable companions of pens—but I never got around to doing it, at least until now.

Inks are the last thing people think about these days in connection with writing, except perhaps in respect of color, which invariably comes down to a choice among black (business formal), blue (a little more personal), and red (for marking something as “wrong!”). In my late father’s time—he worked as a clerk for a government office, so he used fountain pens regularly—you had the option of using blue-black, very likely as Parker Quink or Sheaffer Skrip, and it’s a color I came to associate with my dad, which is why I keep blue-black as a staple for one of my pens.

The fact is—before fountain pens underwent a kind of renaissance in the 1990s more as a fashion statement than as a clunky writing instrument, followed by a plethora of designer inks—there was a wealth of inks available to the discerning public. You could get them in green, purple, brown, pink, orange, and so on, in brands long vanished such as Carter’s, Sanford, and Stephens’, aside from the in-house inks of the major pen makers such as Parker, Sheaffer, Waterman, Montblanc, and Pelikan. There was also a lively competition among these makers in terms of packaging, specifically in labels and bottles (Carter made exceptionally pretty labels), and the bottles have now become highly collectible on their own, some with their vintage contents intact and still usable after 40 to 50 years.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. How did ink get its start, anyway? At the advent of writing, ink was made from soot or lamp black mixed with gum (says my trusty guide, The Fountain Pen: A Collector’s Companion by Alexander Crum Ewing); red ink was made from vermillion. In medieval times, the quill pen called for a more fluid ink, and this came from tannins culled from vegetables, converted to gallic acid, then mixed with ferrous sulfate (get that?), resulting in a blue-black iron-gall ink, which you can still procure these days. With the steel-nibbed pen (which acid corroded) came inks made with chemical dyes, which also led to an explosion of color.

“The range of ink available by the 1920s would bewilder many people today,” noted Ewing. “It is estimated that the German firm Pelikan alone produced 172 different types, colors, or bottles of ink. There were inks for writing, for drawing, for accountants (which could not be erased), for hoteliers (which could be erased) and so on.”

Which leads me to my first admonition about inks, lest I forget: never put India ink (like Higgins) into a fountain pen; it’s meant for calligraphic and technical pens, and will surely clog your fountain pen’s feed (the part of the pen beneath the nib that conveys the ink), possibly requiring repair. Use only ink clearly meant and often marked “For fountain pens.”

I used to say that I was a pen, not an ink person, in that for the longest time, I limited myself to four basic colors: black, blue, blue-black, and brown. I’m nowhere near becoming an ink fiend—some people collect basically just the inks and couldn’t care less about the pens—but over the past year, I’ve found my desk getting more crowded and cluttered by an invasion of ink bottles, in such sacrilegious colors as Diamine Oxblood and Rohrer & Klingner Alt-Goldgrun (more on these esoteric varieties later). In the ink department, I’m a novice compared to many of my confreres at the Fountain Pen Network-Philippines (at least one of whom, Los Baños-based Clem Dionglay, runs a globally recognized blog on inks, papers, and pens). Ask a newbie question like “What’s a nice bright blue ink?” and you’ll get a dozen responses within minutes (on fpn-p.org), answers such as “Pelikan Edelstein Topaz!” or “J. Herbin Bleu Pervenche!” or “Noodler’s Baystate Blue!”

Ah, Baystate Blue…. Many pen folk swear by it, but I’ve never used it myself, for a couple of reasons: I hate bright blue, and BSB (as it’s called, like LSD or MSG) has been notoriously known for staining if not eating into some pens, like vile acid. Some people love flirting with danger, anyway, in the quest of the perfect color.

That quest, of course, is what keeps the ink companies alive—companies that might as well be manufacturing precious wines and perfumes: Noodler’s, J. Herbin, Iroshizuku, Diamine, Private Reserve, Rohrer & Klingner, De Atramentis, and so on. These are no longer your basic Quink and Sheaffer inks that you can buy (and why not?) at National Bookstore. They’re specialty inks, selling on the average for something like P15 per milliliter, or P450 for a 30ml bottle. (To see a mindboggling assortment of these inks, check out a site like www.gouletpens.com, from where we order our supplies if we can’t get them from NBS or the pioneering Scribe Writing Essentials at Eastwood and Shangri-La malls.)

You won’t believe how exotic and even strange some of these inks are. Mahatma Gandhi would squirm if he learned that a 60ml bottle of his namesake ink—produced by Montblanc, in vivid saffron, of course—sells for $100 on eBay. There are inks with extravagant names such as Noodler’s Black Swan in Australian Roses (a lovely deep pink); Noodler’s even has an ink called Whiteness of the Whale, touted to be “invisible during the day, glows under black light.” Some inks are embedded with gold or silver flakes. De Atramentis makes inks that carry scents like apple blossom, or are actually made from wines like chianti and merlot.

And like fine wines and rare vintages, vintage and rare inks now command an audience and a premium. A few weeks ago, educated by online reading, I felt ecstatic to have located and landed two bottles of the now-rare, 1950s Sheaffer Skrip in Persian Rose on eBay for about $10; it’s a flaming pink ink, which makes it highly doubtful that I’ll ever write with it, but just ask the owner of that $300,000 bottle of Chateau Cheval Blanc 1947 when he’s going to take a sip.

Fountain pens come with all different nibs, nib qualities, and filling systems, making ink choice both a pleasure and a pain for the penman (and penwoman). Snooty collectors prefer piston fillers like most Montblancs and Pelikans, but these pistons require patient flushing to get all the old ink and its color out before switching to something new. This is why I generally prefer everyday converters, which make flushing and ink replacement a breeze. To make things even easier, I’ve matched my favorite pens with my favorite inks, going mainly by color—a black pen gets black ink—so I don’t have to guess, when I pick up a pen or two to bring along for the day, what’s in it. And just for the heck of it, I took a shot of these happy combinations, which I’m illustrating this column-piece with.

And I can’t blame you if, after reading this frothy talk about pretty pricey pigments, all you want to say is “Hand me that cheap blue Bic!”

(The inks and pens in the topmost pic are, downwards: Pelikan Blue-Black in the Montblanc Agatha Christie; Diamine Oxblood in the Parker Vacumatic Oversize; Rohrer & Klingner Sepia in the MB Oscar Wilde; Montblanc Carlo Collodi in the Conway Stewart Marlborough; R & K Alt-Goldgrun in the Onoto Magna; Pelikan Brilliant Brown in the Faber-Castell Pernambuco; and Aurora Black in the MB 100th Anniversary.)

Flotsam & Jetsam No. 35: New Pens for the New Year

THE HOLIDAYS and turning 60 this month gave me all kinds of excuses to acquire new pens, and here are two of the best ones: a Montblanc Oscar Wilde, issued in 1994, and an Onoto Magna Classic in tortoiseshell, handmade in the UK just last month. I’m broke but happy 😉

They do look good beside my old mainstay, the Agatha Christie. It’s like having three gorgeous girlfriends to take out on a date (shhhh, don’t tell Beng!).

Flotsam & Jetsam No. 34: Pens Noir

I DIDN’T realize how much more interesting my favorite pens could look until one afternoon this week when—during a long and rather boring meeting at the office—I played around with the two pens in my pocket and with my iPhone, and then applied the “noir” filter in my Camera app. Then I went home and took a few more shots of my other pens. Voila—a whole new way of looking at fine pens.

Flotsam & Jetsam No. 30: My Trusty Agatha

CAN’T BLAME you if you’re sick of this image by now, but am delighted to be with my trusty Agatha Christie, on the road again–this time in Bangkok, where I used it for notetaking at the conference this morning:

Flotsam & Jetsam No. 28: Traveling Companions

AM DOWN in Jakarta for a conference this week and brought two workhorse pens with me for signing books: my ever-reliable 1993 MB Agatha Christie and a 1928 Parker Duofold Senior, the classic “Big Red.”

I originally bought the Big Red for resale, but decided to keep it when I saw how clean it was. Look how sharp the milling is on the black hard rubber part of the cap:

Flotsam & Jetsam No. 25: A Pen Bouquet

Before starting work this morning, I took a quick shot of the pens in my current rotation (note: one of them’s a rollerball):