Qwertyman for Monday, August 11, 2025

A LOT has been said this past week about the 12-0 decision of the Supreme Court on the impeachment case against Vice President Sara Duterte essentially supporting her contention that the one-year rule against bringing up new impeachment charges had been violated by the House of Representatives, and pushing back the earliest date for any resumption of such charges to February 6, 2026.

Predictably, the decision raised a storm of protest involving no less than former Justices of the Court, our top legal luminaries and lawyers’ organizations, and key media and political personalities who accused the Court of judicial overreach. On the other side were somewhat more muted voices calling for respecting the Court’s judgment—including, surprisingly or otherwise, a very sedate Sen. de la Rosa, now all flush with legal wisdom and temperance; to be fair, some of these people were hardly Duterte fans, but likely just citizens tired of all the bashing going on. (The Senate’s subsequent vote to “archive” the impeachment complaint would catch even more flak.)

However this issue is ultimately settled, one thing is clear: the Filipino public’s trust and confidence in their political institutions has hit a new low. And contrary to certain suggestions, it’s not because of journalists and gadflies like me who seem keen on tearing the house down, but because, well—it’s in the nature of the beast (or the human) for something so supposedly venerable as our Supreme Court to behave strangely in certain situations.

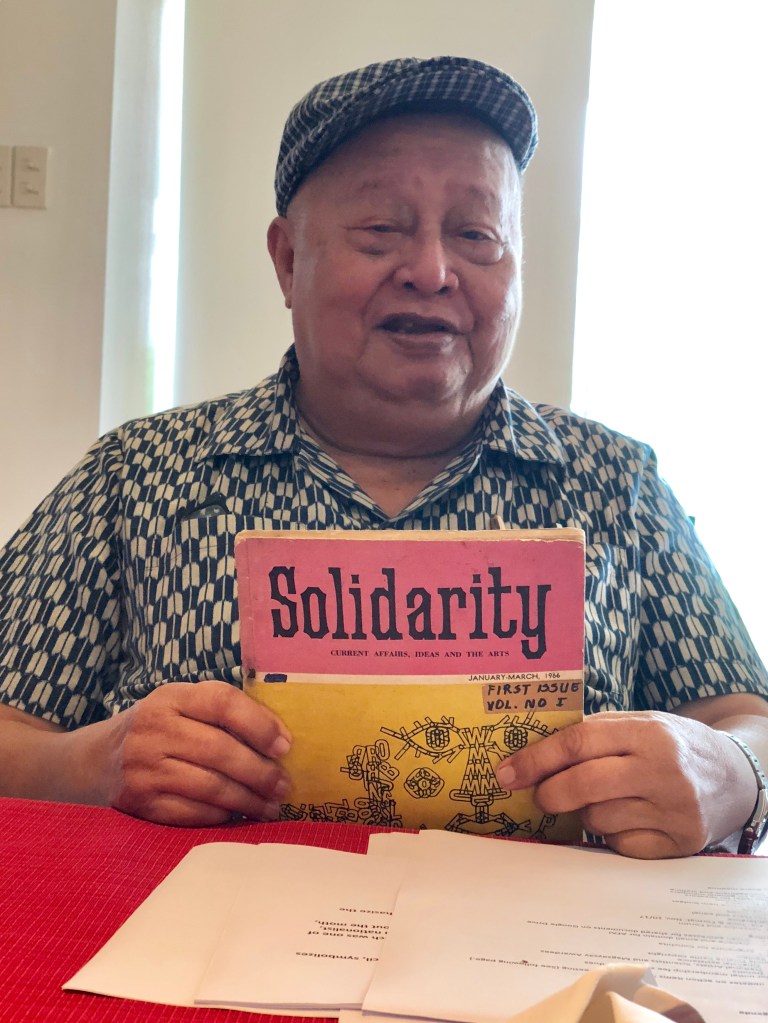

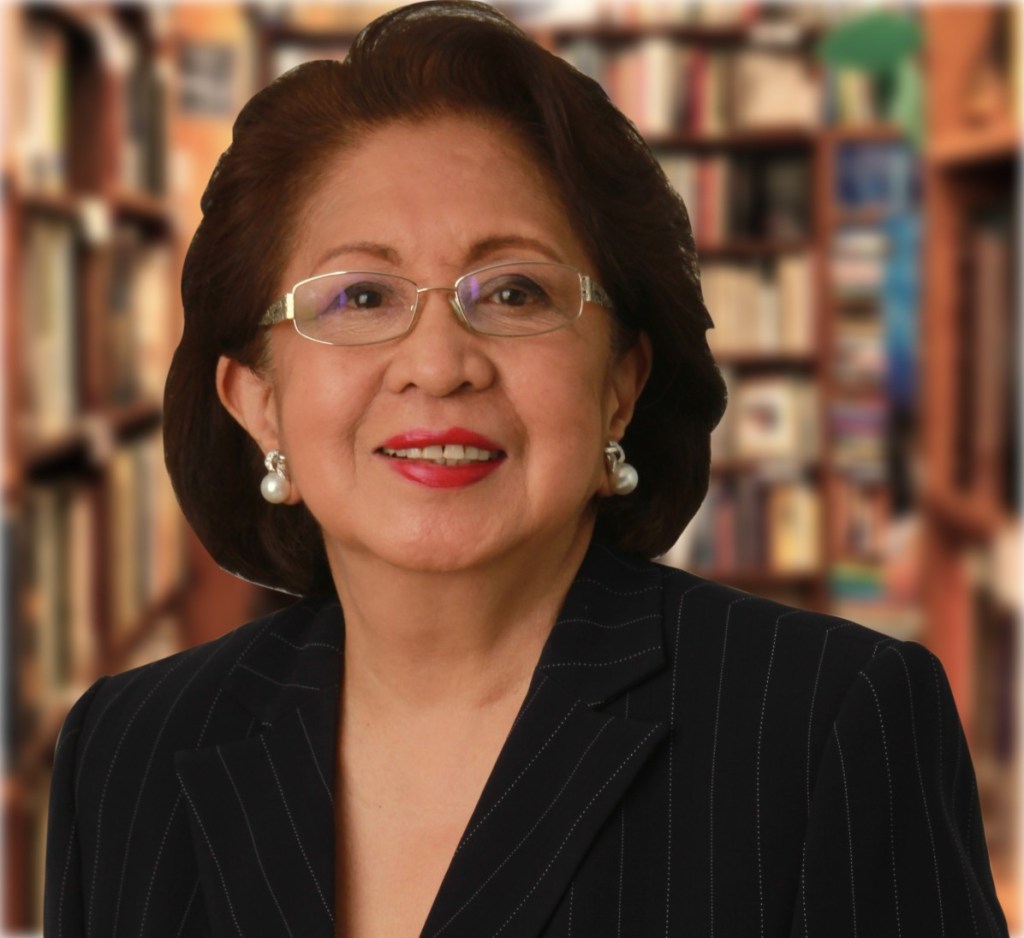

The controversy stirred up by the Court in the Duterte case reminded me of a passage that I quoted in my recently published biography of retired Associate Justice and Ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales, who has also manifested an opinion contrary to that of her current peers. The quotation comes from the former law dean and legal scholar Pacifico A. Agabin, who wrote in his book The Political Supreme Court (Quezon City: UP Press, 2012):

“The Supreme Court, like the US Supreme Court, is both an appellate and a constitutional court. Unlike most countries in Europe, we do not have a constitutional court, and so our high tribunal performs these dual functions under the Constitution. And when it decides constitutional cases, it becomes a political body, just like the executive and legislative branches. ‘Political,’ as used here, means that it acts as a legislature, according to Richard Posner, in the sense of having and exercising discretionary power as capacious as a legislature’s. According to Posner, ‘constitutional cases in the open area are aptly regarded as ‘political’ because the Constitution is about politics and because cases in the open area are not susceptible of confident evaluation on the basis of professional legal norms.’ Thus, when the court decides constitutional cases, it becomes a political organ. Like a chameleon, it changes color and assumes a different role as a political body.

“To repeat, I use the term ‘political’ here not in its partisan sense, but more in its ideological connotations. Unfortunately, there is no dividing line between the ideological and the partisan meanings, and sometimes, these blur into each other. The court itself sometimes fall into the partisan trap.

“This holds especially true in a personalistic culture like ours, where values like utang na loob and pakikisamaare embedded in the Filipino’s subconscious.”

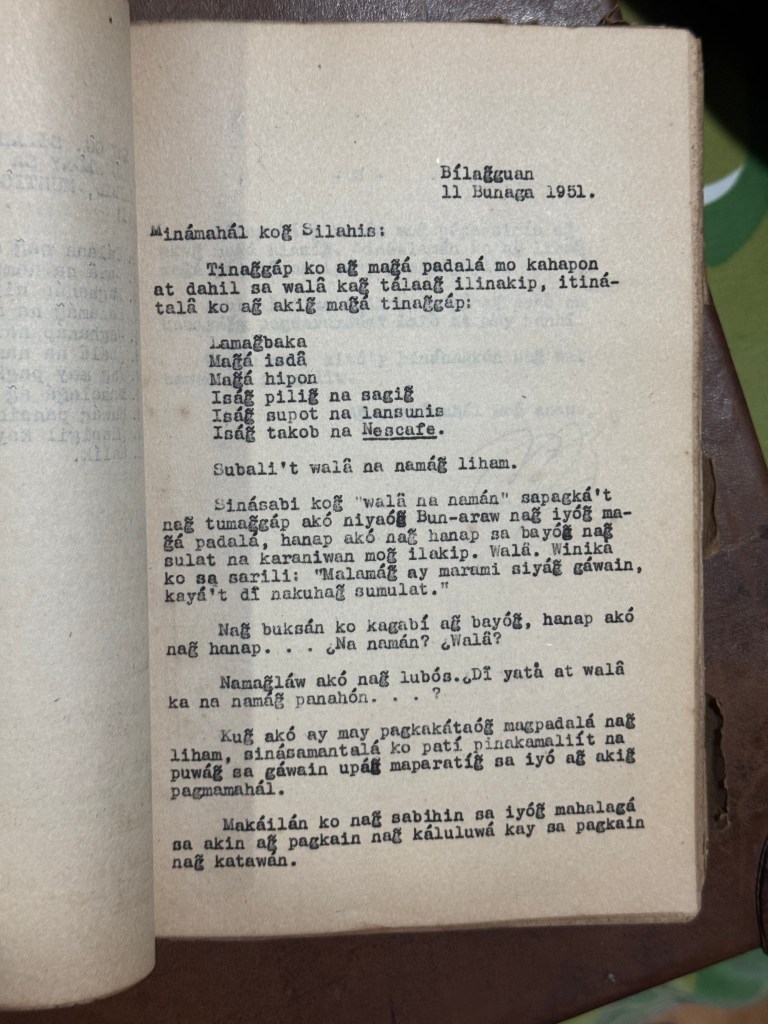

Now, that’s all still very high-minded, but another memory that’s even more disturbing comes from a book that I edited (anonymously, because I didn’t want to be saddled with a libel case—as its author inevitably was): Shadow of Doubt: Probing the Supreme Court (Newsbreak, 2010), written by my friend, the prizewinning journalist Marites Vitug. In her prologue, she recalls this incident:

“During an interview, after I asked an aspiring candidate to the Supreme Court about the unsavory realities of the appointment process, he advised me to tread carefully. The candidate, a Justice of a mid-level court, was fearful of the effects of a book that would pry into the sanctuary of the Supreme Court and ruffle the institution.

“Over an oatmeal breakfast (mine) and coffee (his), he worried that the public may lose their confidence in the Court. He then told me the story of a staff member of a Supreme Court Justice decades ago. This man had access to confidential information and, after learning of Court decisions, immediately approached winning litigants and informed them that he could work on their cases and get favorable results. He asked for money—and, voila, delivered them the good news when the decisions were promulgated. He always had happy clients.

“The Justice I was speaking with was, at the time, working on the Court. Disturbed by the corrupt behavior of a colleague, he reported this to the Chief Justice. However, the Chief Justice took a benign, almost indifferent view. He told the young lawyer that this would soon come to an end because the erring staff member was about to leave the Court; he held a post co-terminus with that of his boss, an associate Justice.

“It was best, the Chief Justice said, to let it pass. He feared that if the Court acted on it and the anomalies became known to the public, confidence in the ‘last bulwark of democracy’ would wane. It was paramount to keep the institution pristine in the eyes of the public, never mind if wrongdoing was gnawing the Court.

“The Justice looked back at this moment and narrated the story to impress on me how important it is to protect the institution. For him and the Chief Justice who initiated him into this misplaced patriotism, strengthening the institution meant glossing over grave offenses.”

I’m not a lawyer (something we very often hear these days, followed by some legalistic opinion), but my pedestrian sense tells me that this Court and this Senate aren’t going to dig themselves out of the hole they’ve jumped into. Pinoy officialdom never admits mistakes and apologizes, like the Japanese do; we love to brazen it out with the thickest of cheeks.

Given that, let’s not hang our expectations on this one peg of VP Sara Duterte’s impeachment. Whether she gets impeached or not, she’ll still have to answer for the serious charges brought against her, perhaps with even more finality than her removal from office will bring.

February 6, 2026 is less than six months away. Let the prosecutors use the time to prepare an airtight case that will secure a clear conviction, in the court of public opinion if not in the Senate tribunal—a case so compelling that it will embarrass any senator-judge who will ignore its logic (and let’s face it, there will be many), and hold him or her accountable to the people at the next election.

In the meanwhile, we have many other and far more consequential battles to fight—our bloated budget, our growing debt, the illiteracy of our youth, the hunger and homelessness of our poor. These can’t be “archived,” and the “forthwith” on these issues came and went a long time ago.