Qwertyman for Monday, September 29, 2025

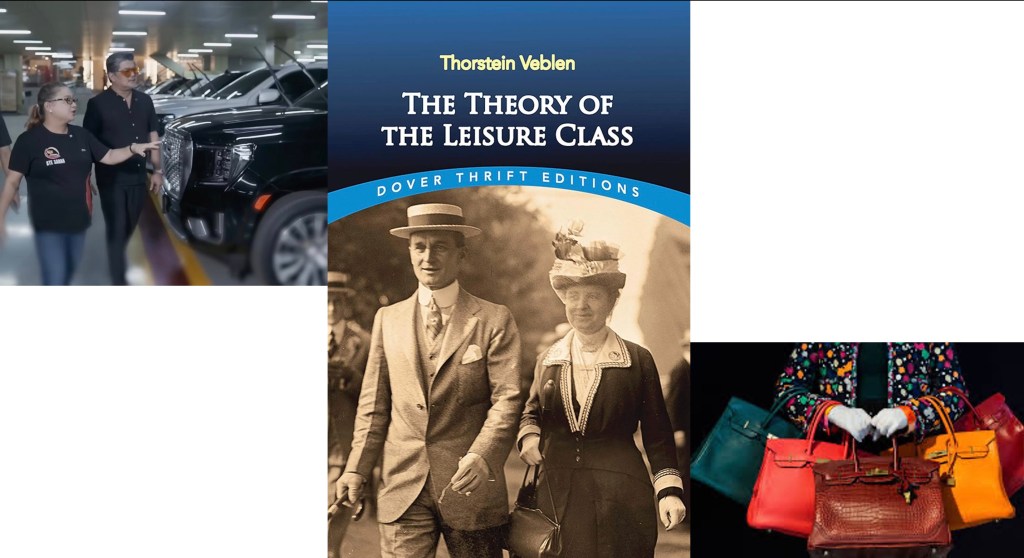

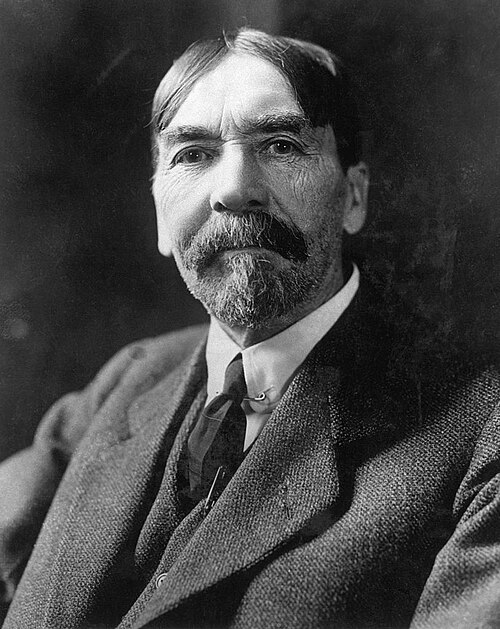

IT WAS during America’s “Gilded Age”—a period that many (not just them Yankees, but also us Pinoys) look back on with borrowed nostalgia—that an economist named Thorstein Veblen wrote a book titled The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study in the Evolution of Institutions (1899).

Drawing on Marx, Darwin, and Adam Smith, Veblen went against the grain of neoclassical economics and its presumption of people as rational economic beings seeking utility and happiness from their labors; instead, Veblen argued, they were irrational agents who amassed wealth for social status and prestige. Writing in a scathingly satirical and literary style, Veblen roasted America’s nouveau riche—the robber barons who had built their business empires on coal, steel, and railroads (think Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Vanderbilt), and who then splurged on mansions, yachts, and such other luxurious testaments to their success.

We don’t remember Veblen much, although he cut a sharp impression among his admirers and critics alike as a dour Midwestern misanthrope, a killjoy who saw little economic value in churchgoing, in etiquette, and even in sports (of course, this was way before the MLB, NBA, and NFL).

What we do remember are some terms that his book bequeathed to our century, most notably “the leisure class” and “conspicuous consumption,” the latter being the purchase and display of goods beyond their practical value for the purpose of manifesting one’s power and prestige—which in itself became a form of social capital, facilitating the accumulation of even more of the same. (Veblen also theorized about “conspicuous compassion” and “conspicuous waste.”)

Dr. Veblen was writing at and about the turn of the 20th century, but his observations were preceded by a history of ostentation as old as, well, Jesus. (And here, being no historian, I’ll acknowledge some help from AI.) The ancient Romans held lavish feasts and circuses to entertain the masses. Their Greek counterparts passed sumptuary laws to curb excess, limiting the gold a person could possess and the number of servants a woman could bring to a public event—which tells us exactly what they were doing. In both feudal Japan and medieval Europe, laws were imposed regulating what people could wear—to preserve social stratification, and visibly distinguish the rich from the poor.

It didn’t always work—empowered by trade, Italy’s growing merchant class brazenly copied what the old nobility wore. Things got so showy that the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola led an anti-ostentation movement in Florence, culminating in the public burning of luxury goods, cosmetics, and elaborate clothing, a.k.a. the “bonfire of the vanities.”

I’m sure you can see by now what I’m getting at, which is the Philippines’ ripeness for its own version of “Bling Empire” and “Dubai Bling,” Netflix shows both devoured and skewered for their “grotesque opulence” and hermetic imperviousness to such inconvenient topics as Gaza, Ukraine, and Donald Trump. I have to admit to binge-watching both series, fascinated and revolted at the same time—fascinated by my revulsion, and revolted by my fascination.

This is how ostentation holds us in its thrall—by indulging our fantasies while providing extravagant proof and reason to cluck our tongues in disapproval. The logical response should be to switch channels, exit YouTube, or just turn the damned TV off. But no, we watch on, bewildered by our inability to comprehend how a Birkin bag could cost $500,000, and further, how someone could afford them, and even further, how someone could own not just one but five of them, and yet even further, how that someone could be a Filipino senator’s wife (last heard opining, with admirable sensitivity to the public temper, that “Now is not the time to attend Paris Fashion Week.”)

Unlike Veblen, who employed sardonic humor to prove his point, this is no longer even satire or damnation by exaggeration, but outsize reality. The gargantuan figures emerging from the infrastructure corruption scandal now transfixing the nation—almost a billion pesos of public money lost in the casinos, P4.7 billion worth of aircraft in one congressman’s hangar, and so on—not only boggle the mind and churn the stomach, but impoverish the imagination. We are too poor to contemplate these sums.

And so to Veblen’s terminology, we must now add “conspicuous corruption,” as it seems that even among the corrupt—who are not anonymous to one another, needing to operate as a cozy network of thieves if they are to mutually succeed—there exists a virtual competition over who can get away with more. This doesn’t even involve or require the building of real assets such as trains, skyscrapers, and power plants, like the industrial dynasts did. Why bother, when ghost accounting will achieve as much if not more for one’s bottom line?

For now, the public outrage over the flood-control scandal may have dimmed the lights for the accused and their accomplices and beneficiaries. Facebook and Instagram accounts that once flaunted luxury limousines, exotic getaways, and designer labels have been shut down or turned private, their owners gone mute after sulky disclaimers to the effect that “We worked hard for our billions!” (But not everyone, as that high-flying congressman’s wife was reported shopping with impunity in Paris last week, oblivious to the brouhaha.)

Not incidentally, there’s more than a tinge of sexism to the recent backlash against so-called “nepo princesses”—the daughters of rich, powerful, and presumably corrupt politicians and their business cohorts. Privileged indolence, after all, is an equal-opportunity affectation, and doubtlessly their brothers aren’t wasting their time volunteering for NGOs and teaching catechism.

When they will reappear is anybody’s guess. The EDSA 4 brewing in the streets should hopefully result in decisive action against the guilty parties in this mess, and if only to appease the mob, I’m sure a few heads will roll. But I’m under no illusion that human nature will reverse course and that Thorstein Veblen’s leisure class and its blingy profligacy will vanish into oblivion anytime soon.

Me, I’m in the mood for a bonfire, and it’ll be more than croc-skin handbags I’ll want to toss into it.