Qwertyman for Monday, October 27, 2025

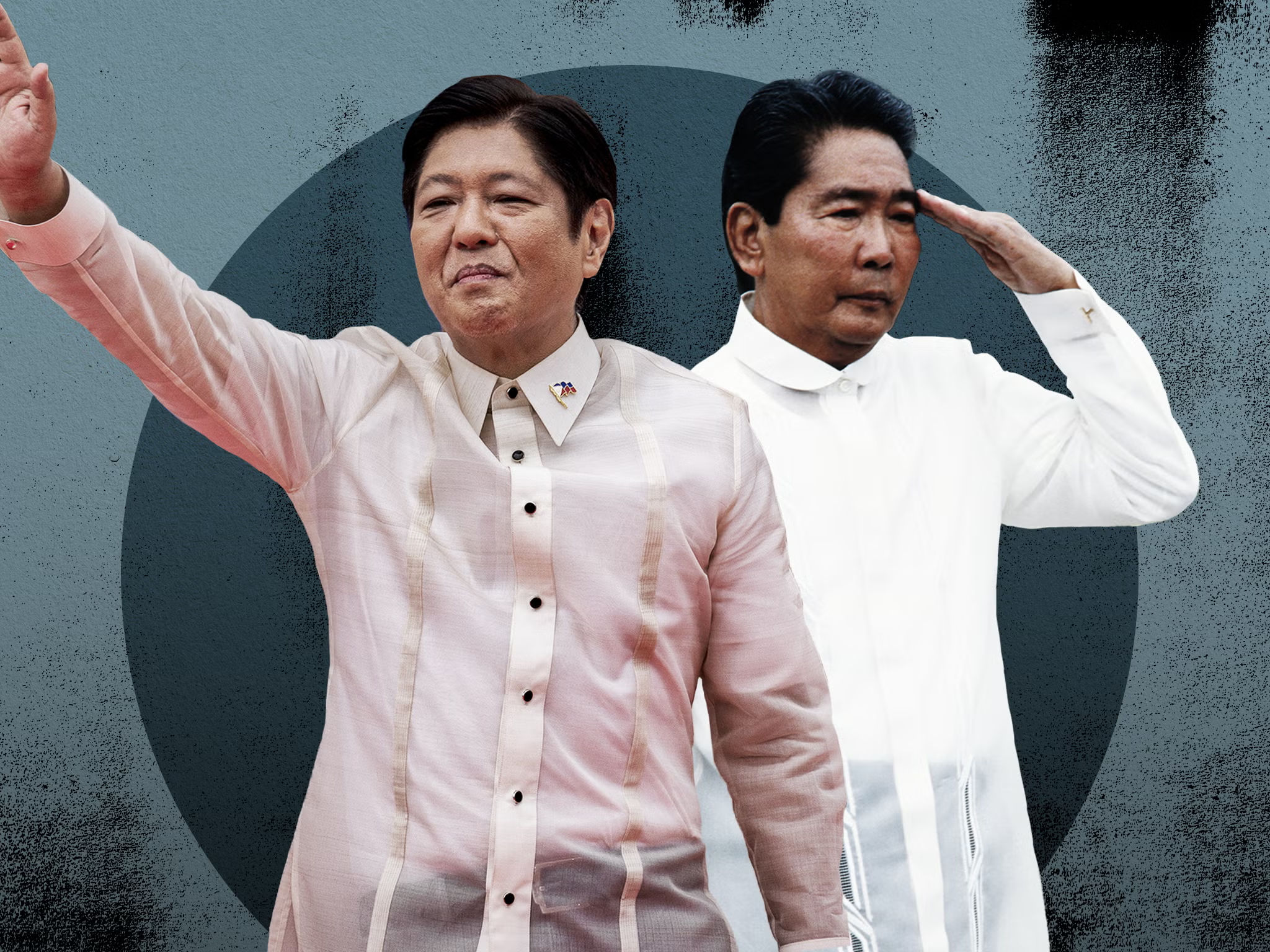

I’VE BEEN going out on a limb for the past few weeks, touting the possibility that President Bongbong Marcos—yes, the son of our martial-law dictator—might be considering doing the right thing and leaving behind his own legacy, one notably different from Apo Lakay’s.

Comes now the news that his spokesperson Atty. Claire Castro—who can usually be counted on for ripostes that elevate the reasonableness of her boss—has been quoted as saying that BBM has been losing sleep conversing with his father (who, let’s not forget, passed on 36 years ago), presumably in search of some advice from the afterlife on contentious current events.

My first reaction was to wonder why their otherworldly tete-a-tete had to take so long, if father and son agreed on the same things. Could they possibly have been arguing? What about? Bank accounts? Sibling rivalry? Forks in the road? And if their encounters leave him sleepless, could BBM be that bothered by FM’s post-mortem perorations on statecraft and, well, craftiness?

This is where VP Sara Duterte enjoys the slight advantage, her father being at least alive and still capable of earthly conversation with Sara on such timely topics as “Your stepmother wants to sell the house in Davao” and “Now where did Pulong’s P51 billion in flood-control funds go?” The Hague may be almost 12,000 kilometers away from Manila, but flying there (on her own dime, she’s careful to insist) beats telepathy or telephony, and creates photo ops with the DDS faithful that nocturnal chit-chats with the departed can’t. (There’s a really nasty and cruel rumor going around, I have to note, that the VP actually wants PRRD to remain and rot away in the Netherlands until he expires—don’t ask me how—just before the May 2028 election, gifting her, like Cory Aquino did on Noynoy’s behalf in 2010, with a wave of sympathy votes. I don’t know if I should applaud or deplore the Pinoy’s political imagination, but there it is.)

Here in Germany, where I’ve just attended the 77th Frankfurt Book Fair where the Philippines was this year’s Guest of Honor and therefore the exotic insect under the microscope, the one inevitable question raised in my many reading and speaking events was “What do you think of the current political situation in your country, and of the fact that another Marcos is now leading it?”

It’s a question I’ve thought about a lot, with or without Frankfurt, and you’ve seen some elements of my answer to it right here in Qwertyman. Pitching these ideas to a foreign audience is a bit more challenging because you don’t have the time to present and explain the details of the context, and you certainly don’t want to lie.

I’m not the Philippine ambassador, I said to them, so I can and will be frank, but if I seem to equivocate then it’s because the situation isn’t as simple as it looks. Yes, BBM is the dictator’s son and yes, I went to prison as a teenager for seven months—many stayed in far longer—under martial law. Yes, I campaigned for his presidential opponent, Leni Robredo, whom I still believe would have made a better president—and yet could.

But very recently, I noted, PBBM has been making moves that have surprised many, for their effects if not their intentions. Whatever he was thinking at the time, his public disclosure of the bigtime contractors likely tied to multibillion-peso scams that some politicians aided and profited from has shaken the country to its core. The public outrage and demand for justice has been so loud and widespread that it has gone far beyond infrastructure into a searing re-examination of corruption in every aspect and at every level of our government and society.

I brought in the Duterte factor, the continuing threat from his own Vice President and former ally, for whom BBM’s surrender of her father to the International Criminal Court could only be unforgivable. The flood-control scandal and its connection with the Dutertistas was, therefore, a bomb set off by BBM for his own political and personal survival, but one with many unintended consequences and casualties, including some of Marcos’ own soldiers, and still possibly he himself, should the stain reach into the Palace as it has been threatening to (with gleeful encouragement from the DDS).

I don’t know how well the Germans understood or accepted my reading—heck, I’m sure many Filipinos don’t—but when you put over a hundred Filipino creative writers and journalists together for a week, some points of consensus are bound to emerge over the breakfasts and endless cups of coffee. Among them: (1) 2028 can’t come soon enough; (2) BBM should double down on the kind of confidence-building measures that will shore up the rest of his presidency, like pursuing the anti-corruption campaign to the fullest, no matter what; (3) only an alliance between idealist (but sufficiently grounded) moderates and BBM’s best people (not to forget his resources) can hope to stop a Duterte restoration.

I’d tell that to my dad, who died almost 30 years ago and who, to be honest and as close as we were, I haven’t seen much of in my dreams. But like BBM and his papa, we’d likely be up all night. Having passed away while the country was still in the capable hands of “Steady Eddie,” when it seemed that Ramos’ vision of “Philippines 2000” was going to deliver us into a new millennium of political stability and economic growth, Tatay would probably crawl right back into his grave were he to be given a day off to witness what we’ve done since.

(Image from The Independentˆ)