Qwertyman for Monday, February 2, 2026

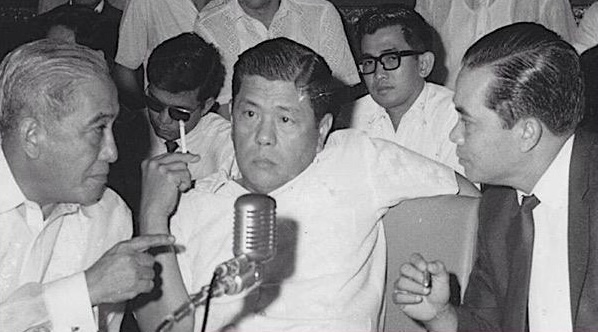

I MIGHT have become a lawyer in another life, given that, back in the sixties, the profession of law still carried with it a certain gravitas, a presumption of not only intellectual brilliance but a commitment to public service. The best of legal minds found themselves in the Supreme Court and the Senate, and the latter was studded with such stars as Jovito Salonga, Jose Diokno, Arturo Tolentino, and Tecla San Andres Ziga. (To Gen Z’ers unfamiliar with these names, Diokno topped both the bar and CPA exams—despite the fact that he never completed his law studies, for which the Supreme Court had to give him special dispensation, and was also too young to be given his CPA license, for which he had to wait a few years. Ziga was the first woman bar topnotcher.)

My father studied to be a lawyer, but other priorities got in the way; his dream would be achieved by my sister Elaine and my brother Jess. As for me, activism and martial law happened, and in that environment where the law as we knew it suddenly didn’t seem to matter, I lost any urge to enter law school, and chose between English and history instead.

Thankfully, many others saw things differently, and now make up the cream of the profession, appearing on lists such as the Philippines’ Top 100 and Asia’s Top 500 Lawyers. Their skills are formidable—I’ve been told that some senior lawyers are so sharp (or so, shall we say, highly persuasive) that they can get a Supreme Court decision reversed—and their fees will certainly reflect that.

But my utmost admiration is reserved for lawyers who have devoted their careers to that portion of the Lawyer’s Oath that says: “I shall conscientiously and courageously work for justice, as well as safeguard the rights and meaningful freedoms of all persons, identities and communities. I shall ensure greater and equitable access to justice.”

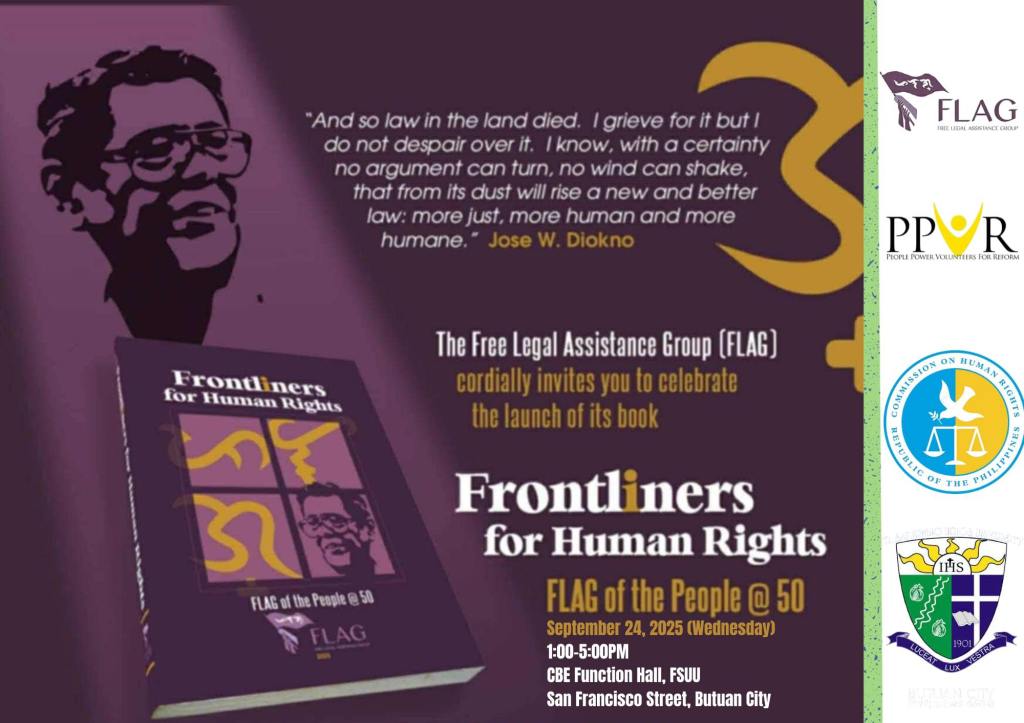

No better group of lawyers represents that than the Free Legal Assistance Group or FLAG, founded in 1974 by Diokno himself, then newly released from prison, together with Lorenzo M. Tanada, Joker P. Arroyo, Alejandro Lichauco, and Luis Mauricio, all fellow members of the Civil Liberties Union of the Philippines (CLUP), as martial law entrenched itself and civil liberties became increasingly threatened.

In the half-century since then—documented in FLAG’s anniversary book Frontliners for Human Rights: FLAG of the People @50 (FLAG, 2025)—FLAG has worked to locate and release desaparecidos, or persons abducted by State agents, fight the death penalty, defend victims of extrajudicial killings, and contest the Anti-Terrorism law, among other key initiatives.

“From its birth, FLAG has kept faith in its philosophy of developmental legal advocacy—the adept use of the law and its processes and institutions not only to secure rights and freedoms but also to change the social structures that trigger and perpetuate injustice,” FLAG reports. “Over 50 years, FLAG has handled over 9,052 cases and assisted over 9,591 clients throughout the country. These figures are merely a fraction of the cases FLAG has handled, and the clients FLAG has served nationwide. The number of FLAG clients excludes the communities and barangays who had experienced massacres and hamletting, urban poor communities whose homes had been demolished, and landless farmers and tenant farmer associations, whose numbers are impossible to count. Overall, FLAG’s rate of success ranged from a low of 66.89% (in 1989) to a high of 79.11% in 1990. On average, FLAG has won 7 out of every 10 cases it has handled, or an impressive success rate of 72.92%.

“FLAG has always provided its legal services, free of charge. In line with its core mandate, FLAG renders free legal assistance primarily to those who cannot afford, or cannot find, competent legal services. FLAG counts clients among the urban poor, students, indigenous peoples, farmers, fishers, political prisoners, and non-unionized or non-organized workers.”

These gains have come at a huge personal cost—no less than 14 FLAG lawyers have died in the line of duty, presumably at the hands of State agents. FLAG lawyers have been Red-tagged, harassed, and put under surveillance.

That hasn’t stopped its lawyers from pursuing their mission under its current Chairman, former Supreme Court spokesman Atty. Theodore Te. The need for their services certainly remains, with the Philippines ranking 38th out of 170 countries in the world in the 2023 Atlas of Impunity released by the Eurasia Group for “impunity,” defined as” the exercise of power without accountability, which becomes, in its starkest form, the commission of crimes without punishment.”

We can only wish Ted Te and his courageous colleagues well, as they operate in an environment more complex in many ways than martial law.

Speaking of law books, I’d like to recommend another book that was launched just recently, Constitutional Law for Filipinos: Mga Konsepto, Doktrina at Kaso (Central Books, 2026) by Atty. Roel Pulido. One of our leading environmental lawyers, Atty. Pulido teaches Constitutional and Environmental Law at Arellano University, where he also serves as Director of the Office of Legal Aid.

“This is a project designed to be a learning aid,” says Roel. “It has a few unique features. First, It does not explain each and every Article of the Constitution. Instead, it focuses on Constitutional law concepts. Each concept is explained in simple language. Then Supreme Court rulings explaining the concepts are quoted. And in a box, I have placed a short and simple Filipino explanation of the concept. Second, the cases are quoted to explain and elaborate each concept. Instead of including all the convoluted issues in one case, it focuses only on the topic at hand. Third, the doctrine of each case cited is summarized in a sentence in both English and Filipino.”

We need more books like this that make the ideas and the language of the law more accessible to ordinary Filipinos. That’s the first requisite of legal literacy, which is also a form of empowering people. FLAG and Atty. Pulido are the kind of lawyers I would have wanted to become.