Qwertyman for Monday, March 17, 2025

IN PLAYWRITING and fiction, we call it deus ex machina—literally, the “god out of the machine”—which has come to mean a miraculously happy or fortuitous ending to a long and agonizing drama.

You’ll find it, for example, when a virginal heroine—beleaguered by dirty old men and rapacious creditors—seems on the brink of yielding her precious virtue, tearfully praying on her knees for deliverance, when a kindly lawyer comes knocking on her door to announce that a distant uncle has passed away, leaving her his fortune. We rejoice with her—despite feeling, at the same time, that divine intervention came a bit too conveniently. This is why I admonish my students to refrain from employing deus ex machina in their stories, because in today’s hard-bitten and cynical world, nobody really believes in it anymore, and readers simply feel deprived of a more rational ending.

Like many things we know about drama, the idea goes back to the ancient Greeks, whose playwrights used it to great effect, Aeschylus and Euripides among them. Euripides most memorably turned to deus ex machina in Medea, where the title character—having been cheated on by her husband Jason—kills Jason’s mistress and their own two children. Guilty both of murder and infanticide, Medea seems hopeless and bound for damnation—until a machine, actually a crane shaped like a chariot drawn by dragons, emerges from behind the stage. It has been sent by Medea’s grandfather, the sun-god Helios, to pluck Medea away from her husband and from the coils of human justice and deliver her to the safety of Athens.

Was it fair of the gods to save Medea from the punishment awaiting her on earth? It’s arguable, but more than a device to resolve a messy plot, the “god out of the machine” was meant to remind the Athenian audience that a higher order of justice obtained, and that when humanity became too entangled in its own predicaments, then it was time for the gods to take over.

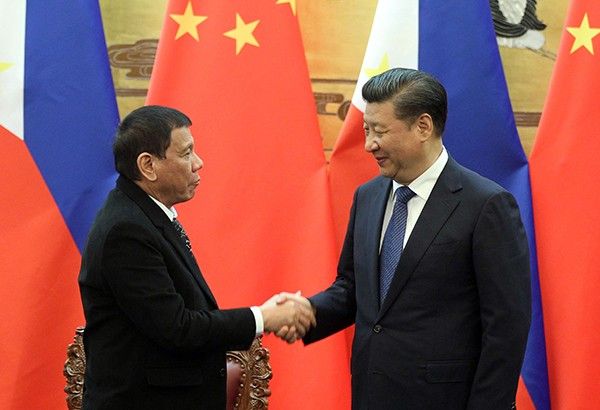

A lot of this swept through my mind last week as the drama of Rodrigo Duterte’s arrest and express delivery to the International Criminal Court at the Hague played out on TV and social media. Had the gods come out of the machine to impose divine justice? It had seemed nearly impossible a few years ago, when Digong was still flaunting his untouchability and taunting the ICC to come and get him. Well, we all know what happened since then—and they did.

We understand just as well that the Marcos administration performed this operation not out of some abounding sense of justice or because it had suddenly acquired a conscience and realized the evil with which it had “uniteamed” to electoral victory in 2022. “We did what we had to do,” President Marcos Jr. explained on TV, with deadpan truthfulness—referring superficially to the Philippines’ obligation to honor its commitment to Interpol, but subtextually to the irresistible opportunity to cripple someone who had become a political arch-enemy, and providentially gain the support of masses of people harmed and disaffected by Duterte’s butchery.

The outswelling of that support—at least for Digong’s arrest and deportation—was spontaneous and sincere. Not since the Marcoses’ departure at EDSA had I felt such relief and exhilaration—and surely the irony would not have been lost on BBM, who knows what it was like to leave on a jetplane, kicking and dragging, for an uncertain future.

And what I say next may go against the grain of everything I have said and thought about the Marcoses, but no matter what ulterior motives may have come into play in this episode of the Duterte-ICC saga, I feel thankful for the resolve and the dispatch that BBM showed in this instance. Along with his administration’s resistance to Chinese aggression in the West Philippine Sea, this will be certain to count among his most positive achievements.

The great difference between this drama and Medea, as an example of deus ex machina, is that the intervention of the ICC (with BBM helpfully providing the crane) isn’t going to save Duterte, but rather the people whom his presidency soaked in blood. But as with Medea, the “gods” step in when local justice proves impotent or inadequate (and did anyone really believe that Duterte would be hauled before and convicted in a Philippine court of law, when even the Maguindanao Massacre took a full decade to produce convictions for the principals?).

The question now is what next—not for The Great Punisher, for whom a prolonged trial at a cushy court will not be punishment enough, but for the Marcos administration, which suddenly finds itself with more political capital at its disposal, and yet also put itself at greater risk? Surely it must also realize that it not only has committed itself to tearing down the entire House of Duterte and confronting the many millions of voters they still represent, but that it has also set itself up for higher expectations, on pain of suffering the same ignominious fate?

In the hopeful bit of theater playing in my mind, I imagine BBM parlaying the bonus of goodwill he has earned from this maneuver into a broader if not genuine resolution to distance himself further from his predecessor and create a freer and more just society. There are clear and immediate steps he can take in this direction. The first gesture would be the release of all remaining political prisoners, followed by the abolition of the NTF-ELCAC, which no longer serves any useful purpose (not that it ever did). He can root out and punish the enablers and perpetrators of Oplan Tokhang and eliminate oppression and corruption from the mindset of Philippine law enforcement. And then he can begin reforming Philippine governance, starting with the quality of the people he seeks to bring to power—senators, congressmen, and the like.

But then that would be the ultimate deus ex machina, and we have been shaped by experience into a stubbornly disbelieving lot.