Qwertyman for Monday, July 14, 2025

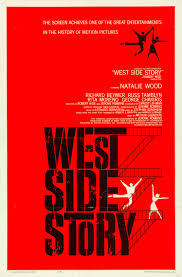

I’VE OFTEN argued that our most popular literary form isn’t lyric poetry, the short story, and certainly not the novel—it’s theater, and more specifically melodrama. Born in the West in the 18th century, melodrama weaves its spell on a suggestible audience through sensational and often ridiculous plots, exaggerated action, overblown emotion, and contrived solutions—all of which viewers happily lap up, and come back looking for more. When you think about it, it also happens to describe our politics, but more on that later.

I used to bring up melodrama when I taught playwriting and screenwriting, by way of analyzing how our Filipino sense of drama works. You don’t have to be a theater scholar or critic to observe that we Pinoys love drama, which to us really means melodrama, whether onstage, onscreen, or in real life.

Subtlety and silence have never been our strongest suit. We like to shout, to scream, to declare, to explain—and to explain some more. Take, for example, our preferred methods of murder. In Hamlet, the villainous Claudius pours poison into the king’s, his brother’s, ear. In The Seventh Seal, a knight faces Death on the chessboard. That may have been thrilling for fans of Shakespeare and Ingmar Bergman—but terribly dull and anesthetic for our kind of crowd.

No, sir, we Pinoys like our killings obvious, loud, and emphatic. Poison in the ear is for sissies. We prefer knives because they mean business, are as personal as personal can get, and they produce a lot of cinematic blood. And it’s never enough to stab someone, certainly not from behind, which would be a complete waste of dramatic possibilities. We like to announce that we’re killing someone, and to explain the reasons why: “Hudas ka, Raymundo, niyurakan mo ang karangalan ng aming angkan, kaya’t tanggapin mo ngayon ang mariing higanti ng hustisya—heto’ng sa iyo!” But of course Raymundo has to have his moment, and must raise that inevitable question: “Ano’ng ibig mong sabihin?” Whereupon our hero launches into another lengthy explanation, to which Raymundo offers an impassioned rebuttal, all to no avail, as he is stabbed repeatedly to the accompaniment of further oaths and recriminations.

I used to think that this kind of talkativeness and effusive gesturing was invented by us, until I went to graduate school and realized that it was all over the place in Restoration drama, where the likes of John Dryden had his characters indulge in copious speechifying in the name of love and honor before killing everyone onstage. I suppose a similar trend seized the French and Spanish theater, and thereby later ours, in the zarzuelas, moro–moros, and komedyas that provided us with both entertainment and education. The noisiness carried over to radio, and then to our movies, which never quite shook off the “Ano’ng ibig mong sabihin?” habit.

And this brings us to our politics, which is not only full of sound and fury, of unbridled verbosity, but of plot twists that strain credulity and yet which manage to keep the audience on the edge of their seats, either roaring in rage, applauding in delight, laughing deliriously, or weeping in sorrow, depending on their persuasions.

The Duterte Saga, our biggest ongoing drama, is now in its fourth act—the Sara impeachment—after the Uniteam victory, the fallout, and the Digong arrest and banishment. A professional scriptwriter could not have done better than giving the VP lines like Sara’s vengeful vows, as the media reported: “I have talked to a person. I said, if I get killed, go kill BBM (Marcos), (First Lady) Liza Araneta, and (Speaker) Martin Romualdez. No joke. No joke,” Duterte said in the profanity-laden briefing. “I said, do not stop until you kill them and then he said yes.” Threatened with impeachment for that statement and for corruption, she said, “I truly want a trial because I want a bloodbath.”

To the uninitiated listener, a madwoman was merely frothing at the mouth, but to the theater-goer, she’s puffing up her feathers, going larger than life, saying outrageous things to define her character and stake out her space like a Maori dancing the haka. Her adversary, PBBM, is playing cool and coy, pretending to be occupied with work and a disinterested party in Sara’s undoing. And yet he whisks off her precious papa in the night to Scheveningen, provoking even more outbursts from the DDS faithful.

Now comes the tearful part. Melodrama moves from Olympian thunder to cloying tenderness, so our next scene, naturally, has Sara’s mom Elizabeth declaring that her estranged husband has been reduced in detention to “skin and bones.” But it’s all right, she says bravely. “And how is my son, acting Mayor Baste?” the Davao City mayor-in-exile asks in a dry croak. “He’s okay, too,” Elizabeth assures him. “His vice mayor is your grandson!” So but for the absent patriarch, all’s well in Duterteland—sort of.

Melodramas love subplots, so let’s introduce one: selling the Duterte house. Common-law wife Honeylet puts up a sign announcing the place for sale (“It’s too painful to sleep there all by myself,” she claims), but son Baste reportedly has the sign removed. Not so fast, VP Sara chimes in; Honeylet could sell her half of it but not her dad’s. Besides, where would Digong live when he returns from the Hague, if Honeylet sold the house? (Cue for hopeful, uplifting music, which tapers off into a melancholic minor key.) “Perhaps he could live with Mama Elizabeth again,” Sara muses.

Ah, such poignant moments. No one’s been stabbed yet—expect a lot of that to happen, metaphorically, if and when the Senate finds its balls and starts the impeachment trial of VP Sara. What’s theater without traitors? Sen. Migz Zubiri has already thrown down the gauntlet by declaring the trial “a witch-hunt.” But Senator Migz, ano’ng ibig mong sabihin?