Penman for Sunday, June 1, 2025

AS ANY friend who’s had the privilege of being invited to his Makati home quickly realizes, Ambeth Ocampo is more than the engaging public intellectual we all know, whose Looking Back series has made history come alive for young Filipinos. He’s also an inveterate collector of rare Filipiniana—books, ephemera, art, and historical objects—all of which come with the territory he works in.

There have been many Filipinos of a similar bent—the legendary Alfonso Ongpin and the late Ramon Villegas come to mind, as well as the more contemporary Jimmy Laya, Melvin Lam, and Edward de los Santos, among others—but the way Ambeth has amassed his collection is noteworthy on its own, as it folds the personal almost imperceptibly into the professional.

It comes pretty close to the classic prescription for murder—means, motive, and opportunity—all captured in his classic story of how he stumbled on and picked up Emilio Jacinto’s silver quill, a writing prize, from an antiques dealer who didn’t bother to learn what it was and let it go for its scrap value. (Having as much of Ambeth’s desire for antiquarian junk but with much less knowledge and certainly less means, I’ve often joked, between the two of us, that Ambeth’s the scholar and I’m the scavenger.)

Jacinto’s quill, along with a trove of other historical treasures from Ambeth’s personal collection, will be up for auction on June 7 at Leon Gallery. They include Juan Luna’s silver belt, Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo’s walking stick, an official copy of the Malolos Constitution, Philippine maps from 1616 and 1647, and the Noceda and Sanlucar Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala from 1860, among many others.

Knowing how precious these objects were, I had to ask Ambeth more about them, and this is what he said.

What made you think of selling these treasures now? Surely it can’t be easy letting go of them after being their caretaker all this time?

Over the years, I have come to the realization that collecting is not the hobby it used to be. As a boy I collected stamps and learned geography, history, and the culture of foreign countries in the process. I was fortunate that my father’s company had an international correspondence, so every week his secretary would send me a batch of envelopes to sort out.

I started collecting Filipiniana books in the 1980s, stocking up from the National Bookstore Quezon Boulevard branch bargain bin where I completed my Nick Joaquin essay collection because they cost one peso each. After school, I went to the Heritage Art Center in Cubao that I learned only years later was the site of the old Philippine Art Gallery. It was a ramshackle grouping of rooms upon added rooms made from old house parts that Mario Alcantara, the owner, bought from mambubulok. I had a favorite nook where I did my homework and when bored I would explore the rooms that I think gave me an eye for art and the ability to choose what I thought was good or not.

Looking back my collecting, and my life, has been the happy intersection of skill and opportunity. Napoleon once said “ability is nothing without opportunity.” I have always seen collecting as a responsibility. Collecting significant Filipiniana is not a hobby. It is not an investment. Collecting is a responsibility, the collector a steward who preserves the collection for the next generation.

The objects I put at auction have enriched my life in many ways and I think they will enrich the life of their next steward. Some of the lots like the Malolos Republic one-peso banknote and the printed copy of the Malolos Constitution have been tucked away in a drawer. If I drop dead tomorrow these might be carelessly thrown away as trash. They should go where they are better appreciated. Collectors de-accessioning keeps the market alive and buzzing.

Let’s get this out of the way: it’s none of our business, but what will you do with the money?

Since I am not a dealer the material reward does not really factor in the equation. I have sold other things before at cost or even at a loss, just thinking that my gain was the enjoyment I got chasing after them and acquiring them. What will I do with the proceeds? When I started selling my rare Filipiniana I thought that instead of having shelves of books, maybe I should just sell and use the proceeds to buy one or two incunabula or samples of early Philippine printing from 1593-1640. Instead of caring for a whole library I will just care for half a dozen very important books.

How did you start out as a collector of historical objects? How and where did you find them? Aside from Jacinto’s pen, what was your most serendipitous find?

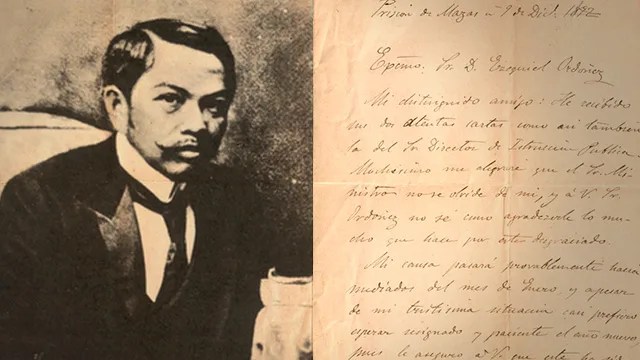

Collecting historical objects came naturally from my work as a historian. I would find things in used bookstores and when supply was still plentiful in the Ermita antique shops. One of the serendipitous finds was the cedula or residence certificate of a certain Julian Felipe, a musician from Cavite. It was in a heap of old papers, initially priced at one hundred pesos. I haggled it down to fifty, paid, and ran away.

Another time my favorite antique dealer brought a “European painting” of a Virgin and Child to my home. I looked at it and knew it was Philippine. When I opened the frame to inspect the painting, hidden under the frame was the signature of the Filipino master Mariano Asuncion (1802-1855). The silver belt of Juan Luna and the bank draft in his name were acquired from Mario Alcantara. It came with the famous trove of paintings inherited by Grace Luna de San Pedro that are now in the National Museum. While everyone was going wild over the paintings, I spent many afternoons browsing the boxes of memorabilia that included the bloodied uniform Antonio Luna wore when he was assassinated, the palettes and brushes of Juan Luna, the memorabilia, some architectural plans of Andres Luna de San Pedro, and much more. I offered to buy the palettes and brushes and the painter’s smock but Mario said these were destined for the National Museum. There was also the last letter Juan Luna wrote to his son from Hong Kong, written a day before his death, not only was this letter significant, Luna did a watercolor of Hong Kong Harbor on the first page of the double-sided letter. All I could afford was the silver belt that came with Luna’s black suit that Mario said was also destined for the National Museum. Unfortunately, the Heritage Art Center burned down and with it all these memorabilia.

Do you or can you separate the collector from the scholar? Did the collecting happen naturally as a consequence of the scholarship?

The collecting grew and was enriched by my research and scholarship. If I had a PhD in Math I probably would not have recognized these odds and ends now considered treasures. I have been divesting over the years. A large part of my Filipiniana collection was donated to the Center for Kapampangan Studies, Holy Angel, Pampanga. All I keep at home are the books I need for work for teaching, lecturing, and writing, but now that I am retired from Ateneo (but still employed on a post-retirement appointment) it is easier to let go.

The full catalog of Leon Gallery’s Spectacular Mid-Year auction can be accessed on its website at https://leon-gallery.com.