Penman for Monday, February 4, 2013

Penman for Monday, February 4, 2013

BEEN LOOKING for a DVD copy of the 1973 Hollywood musical Lost Horizon, a 1954 Omega Seamaster, a pair of Johnny Depp’s Moscot Lemtosh shades, an 11200-mAh power bank for your iPhone, or a 1988 Stipula Baracca limited-edition fountain pen? Well, I have—and I found them all, not in my neighborhood mall or ukay-ukay, but in that largest of global marketplaces, eBay.

I’ve been buying and occasionally selling on eBay almost from the very beginning, since December 1997, and now have a feedback of 520+ (thankfully 100 percent positive). In all those hundreds of transactions, I’ve had maybe three or four bum cases of sellers not delivering, or sending me bad stuff. All of those cases were sorted out and I was refunded, so I do believe eBay to be a generally safe place to shop, with lots of wonderful bargains to be had, but as with any marketplace physical or digital, it can be tricky for the unwary.

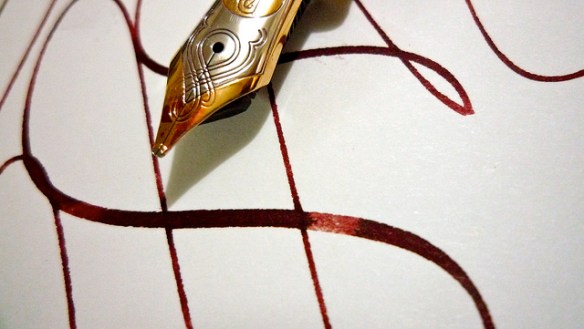

I thought of writing up this brief guide to shopping on eBay because, thanks to my recent articles featuring fountain pens, papers, and inks, I’ve been deluged with inquiries about where to find these items and for how much. In particular, vintage and premium pens seem to be in great demand—pens like the Montblanc 149 and 146, the Parker Duofold, Parker Vacumatic, and Parker 75, and 1920s Waterman pens with flexible nibs.

I’ve sold quite a few of these pens myself, having made a pledge (a pitifully weak one) to trim down my collection of about 200 pens by half. My recent acquisitions have tended to be more expensive, so to help assuage my wallet and my conscience, I’ve had to dispose some of my loot, if only to make room for more. That means that I have to find a steady and reliable source for pens both to resell and to keep, and that can only be eBay—where, at any given moment, there will be about 40,000 pens of all kinds to compete for my attention and my credit card.

So I’ve been telling my pen-seeking friends that they could save themselves a chunk of change by bypassing me and going straight to the source—where a slightly used Montblanc 149 (which sells new on Amazon for $810) might go for around $400. But I’ve also warned them that it’s going to be a slippery slope, fraught with dangers and risks—not to mention the biggest risk of all, which is to get infected with eBay shopaholia.

Even if you care nothing about pens, there are literally a million more things to be found on eBay.com and on its local site, eBay.ph—everything from a mummified monkey’s paw (which you can buy without bidding for $13.00) and an 1864 autograph of Abraham Lincoln (bidding starts at $4,995.00) to a 2012 Lamborghini Aventador (yours for $469,991.00). Very likely, they’ll be things you don’t need but will soon want—and want badly, so mind the following tips if you plan on shopping on eBay without risking your children’s inheritance or your marriage. I’m going to use pens to illustrate my points, but these tips can apply as well to cameras, shoes, bags, bikes, or whatever floats your boat.

1. Know what you’re looking for—know the product and its current market value. Do some research beforehand and establish what possible issues there might be with the item. For example, if you’re looking for a Montblanc, understand that vintage celluloid ones in good shape could command more than new ones in “precious resin”—but also that the 149 and 146 are the most faked pens in the world (along with the Parker Sonnet); eBay actually has a guide to determining fake MBs (which means, know your way around eBay as well). EBay’s “completed listings” is a great way to determine market value—look for the median price (discard lowest and highest prices) for a better sense of what you can expect to pay. Check other websites (Amazon, BestBuy, etc.) as well, because their special deals and offers could undercut eBay. I do most of my gadget shopping, for example, on dealmac.com.

2. Condition, condition, condition. In your enthusiasm for an item, you might forget to probe its condition. Read the description very well and look out for any flaws. Especially scrutinize all the pictures. (This also allows me to spot special features that others might miss—a broad stub on a nib, for example). I think I know pens well enough that I can tell make, model, year, and approximate value for most major brands on sight, but every pen is still unique once it’s up for sale. Keep an eye out for cracks, glue, broken tines, mismatched caps and barrels, discoloration, etc.

3. Set up a PayPal account. It will make your life a whole lot easier on the Internet, since PayPal has become a global standard for electronic payments. I’ve tied my PayPal to a specific bank account I use only for eBay transactions. Is it safe? Of course you’ll hear a horror story here and there, but in my own experience, eBay and PayPal have served me very well, settling questions and disputes and sending refunds very quickly in the rare cases of non-delivery I’ve encountered.

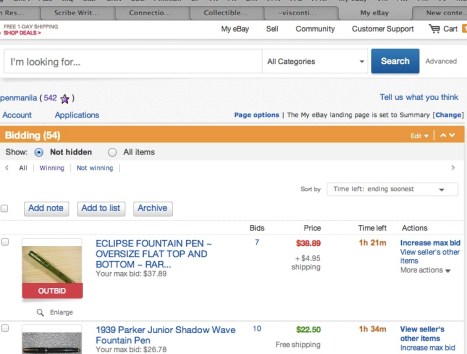

4. Keep looking. Since I now buy and sell pens, I check out eBay many times a day—I have it on my phone—and have set up search terms for my favorite items, like Parker Vacumatics. This enables me to find what I like quickly, in a marketplace where millions of items are up for sale at any given moment. Some of my best bargains have come when buyers in the US—my chief competitors—are literally asleep. I also check out ebay.uk and ebay.ca (the UK and Canada) and have found some of my best bargains there. The first thing I check is “newly listed”, further narrowed down to “buy it now”—this way I can catch the real bargains before anyone else does. Then I check “ending soonest.” You can also refine your searches, for example by looking just for “149” under “Montblanc” under “fountain pens.”

5. Check the seller’s feedback. I’d be wary of a seller with less than 95% positive feedback. He or she may not be a cheat, but has a poor service record (delayed mailings, no response, etc.)

6. Establish your bidding threshold early on. Don’t get caught in a bidding war with another bidder. These days, since I could be bidding on 20 items at any given moment (expecting to win maybe two or three), I just bid my maximum and forget about it until the last two minutes, which are really all that matters on eBay. Some people use sniping programs that let the computer make a last-second automated bid for them; I should, but have been too lazy to set one up, and I rather like the excitement of making the last-minute bid myself.

7. Figure out and factor in your shipping options. Since most of my purchases are made in the US, I use a US shipping address (my sister’s in Virginia) and aggregate my purchases there. When I’ve gathered a boxful, I ask my sister to ship them to Johnny Air Cargo in NYC, which forwards them to me in Manila a week later. I’m sure many of you have US relatives who can do this for you (just make sure that they’re willing—be very nice to them at Christmas). I’ve educated my sister on pens so she’ll know how to check out a pen when it arrives and how to handle and package them properly; and yes, I’ve given her a nice pen or two.

8. Pay promptly, and leave feedback. You’ll see how your own feedback will improve once you become a good eBay netizen.

9. If and when you encounter a problem, report it to eBay. They have mechanisms for dealing with problems like getting a defective item (unless it was so described) or not receiving an item you paid for at all. Take note that there’s a time window (45 days, I believe) within which complaints can be filed.

10. Don’t lose hope. I’ve lost out on bids for items that I’d coveted for years, but then found another one a week later, for cheaper. If you can’t find it on eBay, it probably doesn’t exist, or is illegal to own. For me, it’s fountain pen paradise, and another reason to wake up in the morning for.

Penman for Monday, January 14, 2013

Penman for Monday, January 14, 2013