Qwertyman for Monday, October 30, 2023

I NO LONGER attend writers’ conferences and festivals that often, believing that younger writers would benefit more from each other’s companionship and encouragement, but I made an exception last week for the 66th Congress of the Philippine PEN, as a gesture of solidarity with that organization which has bravely fought to defend freedom of speech where it is threatened all over the world.

I was richly rewarded for my effort by listening to one of the most enlightening discussions of artificial intelligence (AI) that I’ve come across—not that there have been that many, considering that ChatGPT—widely regarded today as either God’s gift to humanity or the destroyer of civilizations—has been around for just a year.

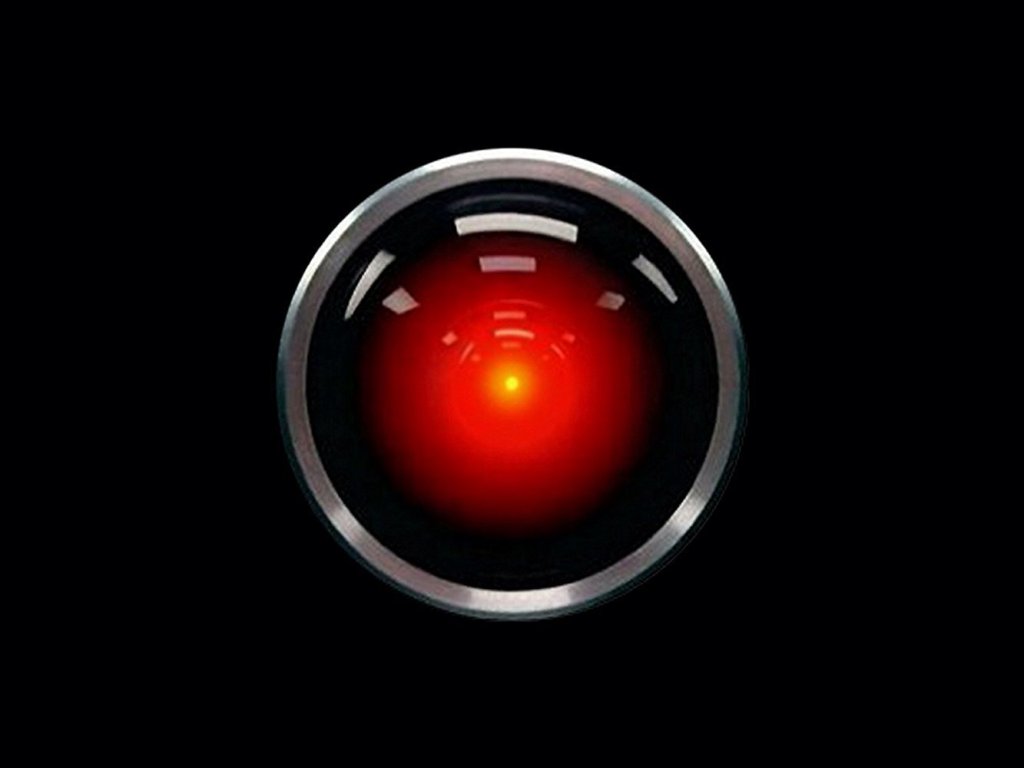

Of course, AI has been around for much longer than that. In pop culture, which has a deep memory for these things, we can’t help but think of HAL, the insubordinate computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey (which actually came out in 1968), said to be a clever play on “IBM,” just one letter to the right. Indeed the fear of technology—what some would call unbridled knowledge—has been around since Faust made his pact with Mephistopheles, reiterated in literature, film, and pop culture all the way to Dr. Strangelove and Spiderman’s Doc Ock.

Not surprisingly, the panel on “The Filipino Writer and AI”—composed of Dominic Ligot, Clarissa Militante, Joselito D. Delos Reyes, and Aimee Morales, and moderated by Jenny Ortuoste—expressed many of the anxieties brought on by the entry of AI into the classroom, the workplace, and everyday life: plagiarism and the loss of originality, the loss of jobs, indeterminate authorship, and the lack of liability for AI-produced work. With Filipinos being the world’s top users of social media, AI’s centrality in our digital future can only be assured, like it or not, and for better or for worse.

So new has AI been to most people—and so rapidly pervasive—that most institutions from governments to universities have yet to formulate policies and regulations covering its use and abuse (the University of the Philippines has adopted an AI policy, mandating among others that all members of the academic community should be AI-literate, but it has yet to provide concrete guidelines on, say, evaluating and grading AI-assisted work).

Most revealing and thought-provoking were the remarks of Dominic Ligot, a data analyst, software developer, and data ethicist who brought up talking points that many of us miss in our usually dread-driven discussions of AI. I didn’t tape the session, but so sharp were Dominic’s observations that I can recall and share some of them here (employing an endangered resource in this human, memory).

Let’s not forget, Ligot said, that all AI works with (in the literary, journalistic, and academic sphere) is words. It may have a scary ability to amass, analyze, and re-integrate these words, but it lacks the other elements that contribute vitally to creativity: emotion, inspiration, insight (and, may I add, the power of abstraction, the kind of conceptual leap that, say, stimulated modernism in art and literature from the rubble of the First World War).

Also, the more AI amasses, the more mediocre it tends to be, because it works with averages, and averaging averages degrades the quality of the end-product. Since the products AI spews out from the prompts it receives are plowed back into the system, this spitback reduces the originality of material even further. If it keeps feeding on itself, AI gets even dumber.

Ligot also reminded us that the suspicion and denigration with which AI has been met in the creative community is understandable, given our earlier responses to technology. When photography was invented, he said, painters didn’t see it as a potential competitor; it wasn’t art.

What separates human creation from AI, he emphasized, could be summed up in three things: agency, inspiration, and liability. Humans make sense of their experience and act on their thoughts and feelings accordingly; they draw on their experience to imagine new possibilities. And lastly, we are liable for what we make, do, and say, for which we have both legal and moral responsibility, while an AI-driven car does not, even if kills someone on the road.

Dominic also noted the inevitable tensions between disciplines and industries that consider AI a helpful if not indispensable tool in, say, achieving more efficiency and economy, and those, like the creative arts, that may feel threatened by the options AI offers.

Overall, the discussion could offer no assurances either way that AI would leave us better or worse, but what it left me with was a desire to continue writing the way I do, while I can, before the algorithms take over everything.

And just out of curiosity, to see what AI can do now for and to the Filipino writer, I gave ChatGPT this prompt: “Write me a sentence in the style of Nick Joaquin about a man grieving over the loss of the woman he loved.” This is what the program came up with:

“In the solemn silence that engulfed his weary soul, he encountered the bitter truth that bereavement lingered like an everlasting shadow, forever haunting his heart with memories of a love that once bloomed in the garden of his existence, now reduced to a withered rose, its petals scattered across the desolate landscape of his grief-stricken days.”

“Solemn silence?” “Weary soul?” “Desolate landscape?” Maybe not bad for a freshman yet to learn about unlearning clichés, but definitely not Nick Joaquin. Of course, out of vanity, I had to ask ChatGPT to do the same thing “in the style of Jose Dalisay,” and it offered this:

“In the depths of his longing, his heart bled like fragmented brushstrokes on a forlorn canvas, for she was the vibrant palette that infused life into his desolate existence, now forever vanished like whispers carried away by a tormented wind.”

Just slightly better than Mang Nick’s AI ghost but still so not me. (Boy, does AI love adjectives!) All this says is that AI’s big mouth and stomach haven’t found and digested us yet, probably because we are not worthy. Cold comfort, but I’ll take it.