Qwertyman for Monday, August 19, 2024

FIRST OF all, a definition of terms, particularly for the benefit of our foreign friends: “epal” is a Filipino word that has nothing to do with friendship over the Internet, although it does presume on some (unearned and likely bogus) level of familiarity between two people—one an achiever (e.g., an Olympic champion) and the other, a politician. The term is rooted in the Filipino word “kapal” or “thickness,” the complete phrase being “kapal mukha” (aka “kapalmuks”) or “thick-faced,” referring to the utter shamelessness some people can be capable of. (EDIT: I’ve been told that “epal” more likely derives from “papel” or “pumapapel” to mean “promoting oneself,” which makes even better sense.)

In the case of “epal,” the specific context is credit-grabbing or publicity-seeking, such as when a politician plasters his or her name all over a civil works project to suggest that it wouldn’t have happened without him or her—or, in recent weeks, when a politician posts a meme supposedly congratulating an Olympic champion, as if he or she had anything to do with that person’s sterling achievement.

Closely related to “epal” in the Pinoy political vocabulary is “trapo,” which started out as “tradpol” for “traditional politician” but which quickly and sensibly devolved into the Filipino word for “rag”—yes, that piece of cloth you mop up the dirty and yucky stuff with. Trapos will find nothing wrong with being epal—it’s central to their trapo-ness—as they are pathologically incapable of modesty or self-awareness, and equate anything that promotes their well-being with the public good, the people being privileged to be served by them rather than the other way around.

We witnessed this in abundance in the wake of the Paris Olympics, from which the Philippines came home with two golds and two bronzes. In what Netizens quickly dubbed the “Epalympics,” our medalists, especially gymnast Carlos Yulo, were showered not just with congratulatory memes from the usual politicos but with tons of cash and other goodies from both public and private donors.

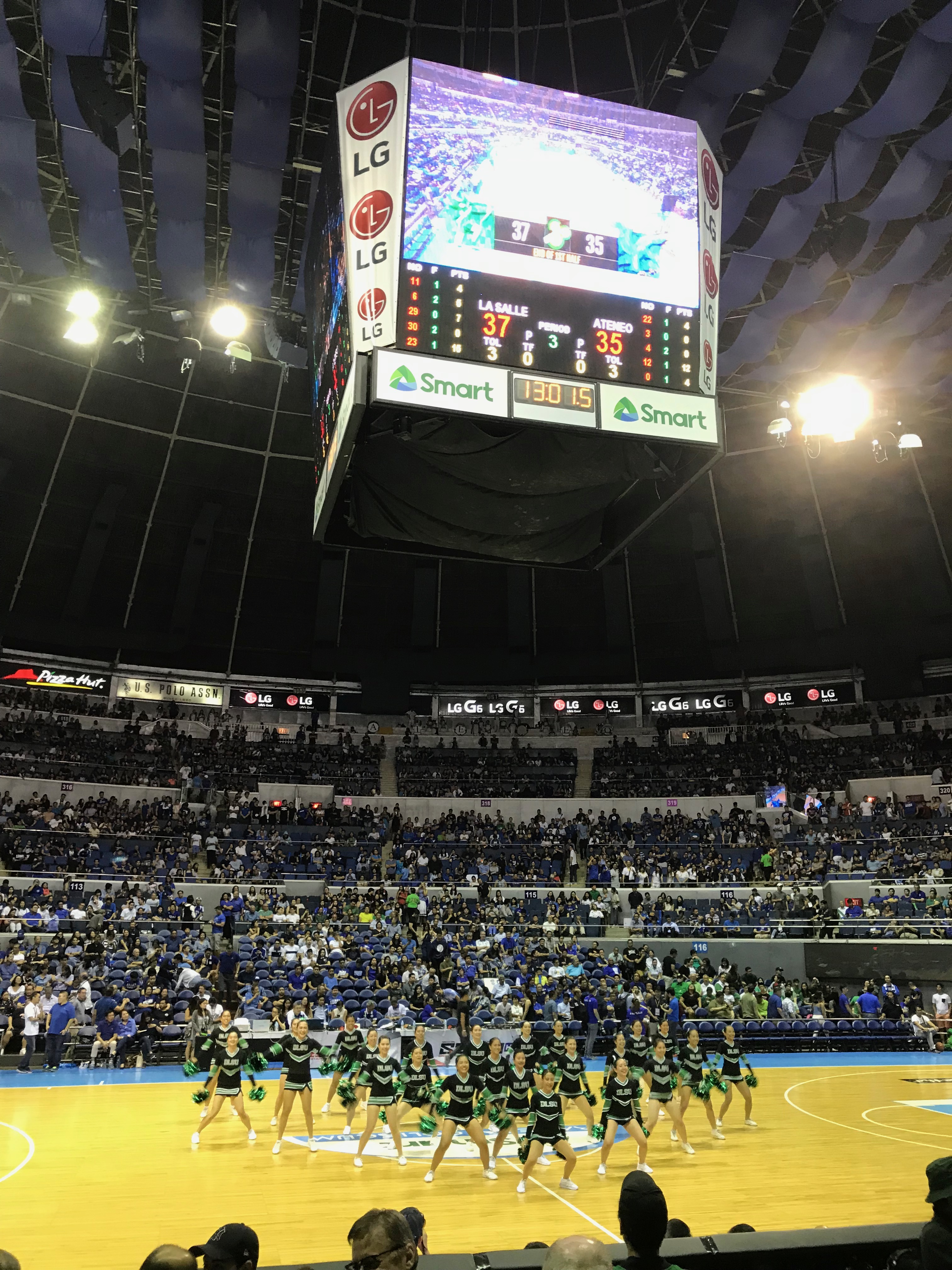

There’s nothing, of course, preventing our distinguished and hardworking public officials—and even those seeking to replace them—from sharing in the post-victory jubilation. Lord knows we needed that boost to our spirits, even if our national fantasies still revolve around basketball like nothing’s happened since Berlin 1936 (there’s something to be said here about our propensity for self-punishment and martyrdom, but we’ll leave that for another time).

It’s possible that Caloy was looking forward to the chorus of fulsome praise from his favorite senators and congressmen, if only as a relief from all the messages urging him to either disown his mother or to find another girlfriend shaped more like, well, a gymnast. A politician, after all, represents a constituency and presumes to speak for them, so it has to be extra comforting to realize that it’s not only Cong. X speaking for himself, but all 250,000 voters in the third district of his province, even if none of the appear in the meme; heck, even Caloy himself may not be in the picture, but does it matter? He has all the glory he needs; let him share it with the less fortunate.

As a writer, however—and speaking on behalf of my fellow artists—I must register my complaint over the apparent partiality of our esteemed epals, who have never congratulated me or my colleagues despite our considerable achievements on both a national and global scale. Not even my local councilor or barangay captain greeted me when my novel was shortlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize, nor did the UP Singing Ambassadors and UP Madrigal Singers receive online hosannas for their triumphs in Arezzo. (This list can go on and on to include our prizewinners in film, painting, sculpture, etc.) No, sir—our epals are staunchly and singularly sports-minded, perhaps in commiseration with athletes who have to run, vault, gyrate, box, and even shoot their way to victory; politics, after all, is an ancient blood sport, at which not necessarily the best but the strongest survive.

Come to think of it, I can’t recall a senator or congressman congratulating journalist Maria Ressa (save for a few brave souls in the opposition like VP Leni)—let alone give her a million-peso bonus—for winning the Nobel Prize, which will probably take another century for another Pinoy to get.

Yes, let’s talk about those bonuses—which all of us are happy our sports heroes are receiving and frankly envy them for, there being no such generous windfalls in our line of work. It’s another sure sign of ka-epalan when the “incentive” is given after the fact of victory, and not before when it might have mattered more, and not just to one champion but to an entire program in dire need of such basics as food, uniforms, shoes, and transportation money. (One deathless politico even offered Yulo an extra P5 million if he were to reconcile with his estranged mom—awww, so touching! You can bet he’ll be there with an outsize check when the tearful moment happens.)

Yes, Yulo & Co. did receive government and private help on their way to the Olympics, for which they’ve been properly thankful, and yes, those investments clearly paid off. But where were all these mega-millions for the grassroots sports programs that could have produced a dozen more Caloys? Yulo himself has nobly announced that he will share his bounty with up-and-coming gymnasts, and bless him for that, but that’s not even his job.

The most cringeworthy prospect yet lies ahead: who among our Epalympians will succeed in getting Caloy Yulo on his or her campaign poster come the elections in 2025? And God forbid, will Yulo himself do a Manny Pacquiao and tumble his way into the political arena down the road? As we say in these drama-dizzy islands, “Abangan.”