Penman for Monday, June 16, 2014

Penman for Monday, June 16, 2014

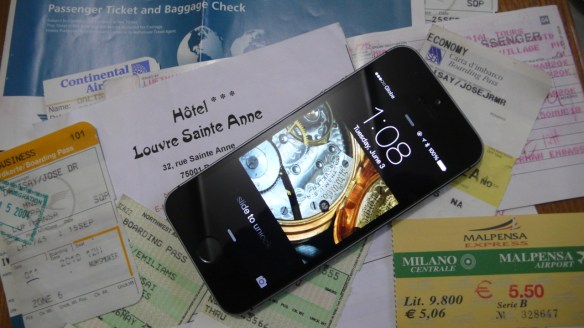

LAST WEEK I wrote about some websites that you could check out if you’re planning to go on a trip, especially to some place you’ve never been before. Practically everything today can be planned online, from choosing destinations to booking flights and hotels and buying travel insurance. But what about when you’re already on the road?

This is where travel apps come in—“apps” being those small programs or applets (little applications) that come with your tablet or smartphone, or that can be downloaded to them. These apps can be lifesavers—literally, when you’re lost close to midnight in the bowels of a subway station in a strange city, without the foggiest idea how to get back to your hotel. Some will require an Internet connection, but many won’t, after their initial installation—and that’s when you’ll be happy and relieved that you had the foresight to install them when you could, before you even left for the airport. Whatever I’ll list here won’t be your only options—in many cases, there may even be other, better apps other will know about—but these are the ones I’ve roadtested myself, over many years of traipsing around the planet, with PDA (remember those?) or smartphone in hand. (Do note that I use an iPhone, but many of these apps gave their Android counterparts. For IOS devices, go to the App Store.)

Trip planning. If you travel often, you’ll need an all-around planner to organize your trips—remind you of your itinerary, make your bookings, check your flight status, provide weather forecasts, convert currencies, and such. Your datebook can take care of some of these things, but not all. For many years now, my reliable sidekick in this department has been an app called WorldMate, which can do all of the above, and more (it can also calculate tips).

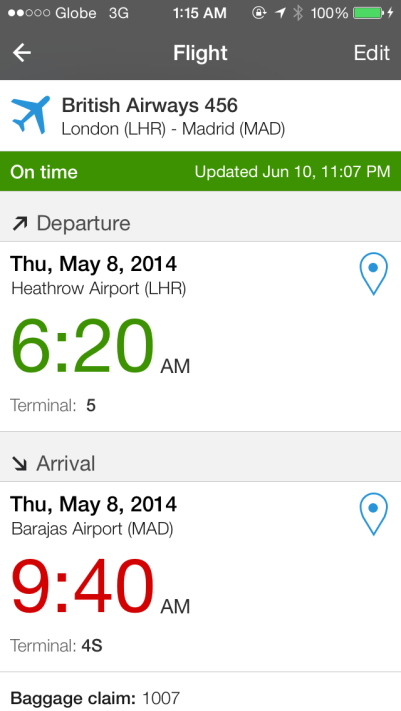

WorldMate’s strongest feature is its flight planner and notifier, which comes in really handy when you have a string of flights to take in a mad dash from one airport, one terminal, and one gate to another. Let’s say you’re flying Delta to Detroit via Tokyo Narita, or Cathay to London via Hong Kong. As soon as you make your booking and receive it in your email, all you do is forward your confirmation email or e-ticket to trips@worldmate.com. WorldMate will automatically digest that email and reflect your itinerary on the app on your phone or tablet—and, if you’ve configured WorldMate to sync with your datebook, it’ll show up on your calendar as well. If your flight gets delayed, WorldMate will advise you of it. It will give you your terminal on arrival and departure. (WorldMate has a free basic version and a paid Gold version with more features.)

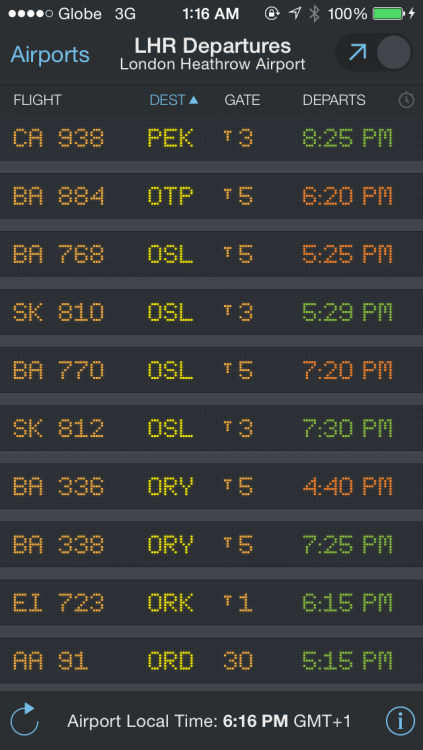

Flight tracking. You’re dashing to the airport in a cab, late for your flight, and you don’t even know which terminal or gate it will be leaving from (and if you’re really unlucky, you’ll be in Madrid, where Terminal 4 is several kilometers away from Terminal 2, and Terminal 4S takes another 20 minutes to get to); you’re praying like mad that your flight’s delayed. At this point, your friend is an app called FlightBoard, which tracks scheduled flights—arrivals and departures—at airports all over the world in real time. A similar app called FlightAware allows you to track all the flights between two airports for a given day, and to zero in on a particular one; if it’s up in the air somewhere over Siberia, it will show exactly where it’s supposed to be on a global map, much like you’d see on those onboard monitors. Both FlightBoard and FlightAware are free. (These apps are also good for when you’re meeting someone in Arrivals.)

Getting around. Once you’ve reached your destination, there are two things you’ll almost certainly need to get around: a city map, and a local transport (subway and bus) guide. Many airports will give you free city maps on arrival, and they’re fun to spread out on the table over breakfast to plan the day, but they’re a hassle to unfold at streetcorners and in the middle of the plaza to locate where you are and where you’re going (and at that instant, you might as well wear a T-shirt saying, “I’m a lost tourist—please, victimize me!”).

A good map stored in your digital device—without needing to go online, as you would with Google Maps—can save you a lot of anxiety, if not a lot of footsteps. On our recent sortie around Europe, I was glad to be guided by one invaluable resource: Ulmon maps of Barcelona, Venice, Florence, and Paris. All of these maps were free, and could be blown up to the level of individual streets and even alleys; if you feel lost, you could input the name of the nearest street, and it will locate your neighborhood in relation to popular landmarks. Clicking on the name of a hotel will give you rates; public transport stops are also indicated.

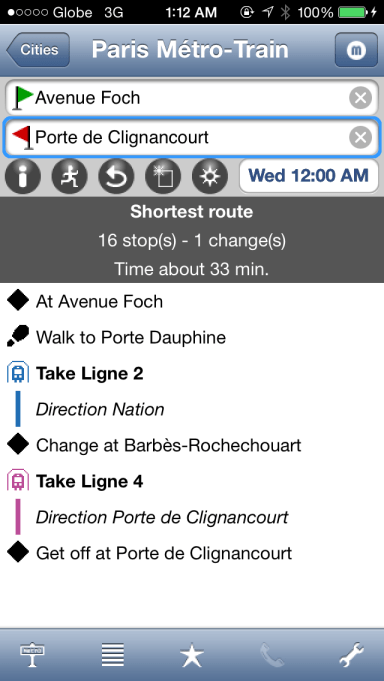

Speaking of public transport, nearly all the major cities of the world have some kind of subway or metro rail line, and this gives me an opportunity to introduce my favorite travel app of all time—and I mean that almost literally, because I’ve been using it in its various incarnations since 1999, or 15 years, an eternity in digital time. It’s called Metro, and it’ a guide to the world’s subways, metros, and bus lines. I first used Metro on my Palm Pilot when I was navigating around London, and the app—though regularly updated—has remained essentially the same. You choose a city (say Paris), and decide that, from your hotel on Avenue Foch, you want to go to the weekend flea market at the Porte de Clignancourt. You input “Avenue Foch” and “Clignancourt” and tap an icon, and Metro will yield the information that the shortest subway route will take 16 stops involving one change (at Barbes-Roucheouart—thankfully, you don’t need to know how to pronounce these names), for approximately 33 minutes total. Each subway stop is identified, as well as the direction of the train you should be taking. The best thing about Metro? It’s absolutely free, and works offline.

This list of apps could go on, but as travel is complicated enough, let’s keep it simple: for as long as you have these apps (WorldMate, FlightBoard, Ulmon Maps, and Metro), your next trip will be much less of a headache, and you can enjoy the view out the window rather than wonder and worry over where your train is going.

(Let me just add, before I forget: these apps will be totally useless if your phone or tablet is dead; I always travel with a universal adaptor, an extension cord, and a power bank for extra juice. If you blow air into my pants, I could go on a spacewalk.)

Penman for Monday, August 5, 2013

Penman for Monday, August 5, 2013