Penman for July 9, 2023

A NEW book launched last month by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas once again brings up how unlikely—and yet in a way also how logical—it is for a nation’s central bank to be the repository and protector of the country’s cultural heritage.

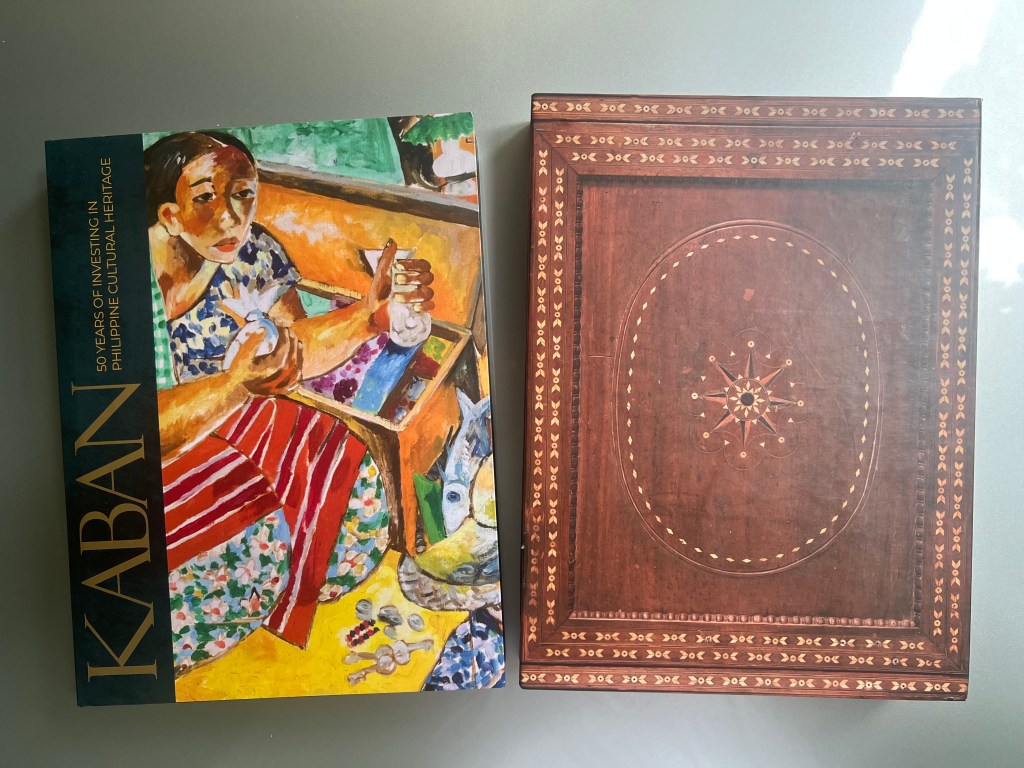

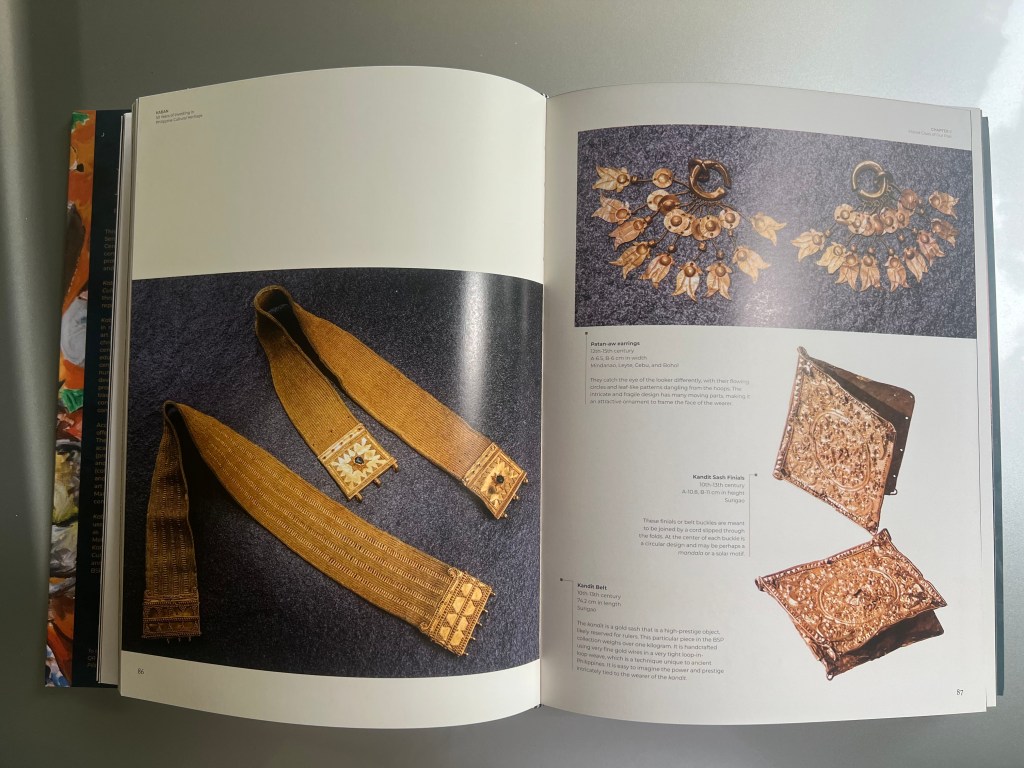

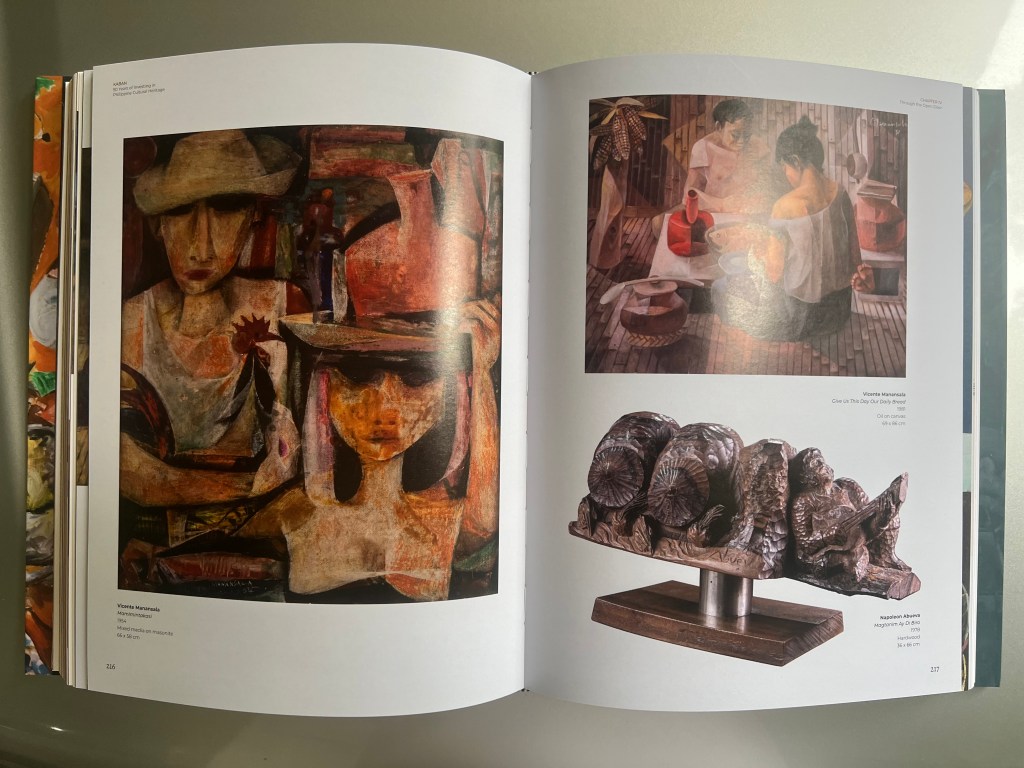

Simply titled Kaban (treasure chest), the sumptuous 340-page book offers a guided tour of the BSP’s fabled cultural collections, from pre-Hispanic gold to contemporary art, with each section curated by experts in the field. The book’s writers include Portia Placino, Victor Paz, Dino Carlo Santos, Clarissa Chikiamco, Tessa Ma. Guazon, and Patrick Flores; I contributed a preface, from which I quote some excerpts below.

Banks represent resources, stability, and continuity, and central banks even more so, for the financial sector. They will often purchase art for décor, and perhaps even for investment; but they will not routinely spend vast amounts on the acquisition, storage, and exhibition of valuable cultural artifacts, as the BSP (and its predecessor, the Central Bank) has done.

Only inspired and visionary leadership can achieve this fusion between the seeming banality of money and the transcendence of art. The Central Bank and BSP have had the good fortune of being led at various times by men who embodied this integration—among them, the CB’s founding father Miguel Cuaderno, a lawyer with a passion for history, culture, and art.

Decades later, Cuaderno was followed at the Central Bank by Jaime Laya—a banker, accountant, writer, collector, and cultural administrator. It was under Gov. Laya that the Central Bank embarked on its most ambitious acquisitions and began to be known for minding more than the nation’s money, but its cultural heritage as well.

Cuaderno and Laya were supported by the likes of Benito Legarda, at one time the Central Bank’s head of research, who was not only an economist but also an avid numismatist and historian who initiated the Money Museum, which became the base for the bank’s later forays into other areas of culture.

The release of Kaban—following a series of other beautifully produced books about the precious objects in its collection—highlights the value accorded by the BSP to the idea of wealth: its generation, propagation, and preservation, which is, after all, the core business of banks. But this isn’t just flaunting wealth for wealth’s sake, an exercise in ostentation and in investment by the numbers.

The BSP collection is imbued with historical and cultural value, and the objects in its catalogues—from ancient coinage and currency to contemporary art and furniture—are physical embodiments of the things and notions we hold dear, our sensibilities and aspirations as a people, the heritage and the legacy we want to pass on down the generations. It is another bank, a cultural bank, but one whose elements have been carefully chosen and curated to reflect our finest traditions and brightest memories.

It’s interesting and important to note that the BSP is not alone in this extracurricular preoccupation. Beyond the Philippines—where many other banks and financial institutions have been known for their impressive art collections and generous support for culture—banks around the world have associated themselves with art, amassing stupendous collections and employing art to project a positive and more humane image of what most people might otherwise see as cold and soulless financial corporations. Indeed, Professor Arnold Witte of the University of Amsterdam calls banks “the new Medici,” referring to the Renaissance’s most important patron of the arts, Lorenzo de Medici, not incidentally himself a banker.

Among the world’s most important art collections held by banks, that of the Banco de España in Madrid goes back to the late 15th century and forward all the way to contemporary sculpture and photography. The Swiss UBS holds 35,000 pieces of modern art. JP Morgan Chase, the Bank of America, the Royal Bank of Canada, the European Central Bank, and the Societe Generale have also been leaders in the field.

Central banks have also been known for their art collections, although their origins, sourcing, and contents vary. According to a report by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, “In the US, the Federal Reserve’s fine arts program was established in 1975 by Chair Arthur Burns in response to a White House directive encouraging federal partnership with the arts. Unlike other collections, the Fed relies on donations of artwork or outside funds to purchase works of art.

“Most European central banks’ art collections consist mainly of paintings, but this is not a global trend. In Colombia, Costa Rica and the Philippines for example, the central banks are also home to museums with exhibits ranging from archaeological treasures to medieval goldwork and pottery.

“The central banks of Colombia, Austria and South Africa, among others, host catalogues of their collections on their websites. The Central Bank of Iran’s website hosts a video documentary on the Crown Jewels collection. Many other central banks including Greece, Hungary, the Netherlands and the Philippines have physical catalogues of their collections, though these have not been digitalized.” It quoted then Governor Amando Tetangco as saying that “The BSP ensures that outstanding examples of Filipino genius in its gold, art, and numismatic collections are shared with the people through exhibits, books, CDs, social media, and provincial lectures.”

This puts the BSP in the fine company of other central banks that have recognized the special relationship between monetary and cultural wealth, and the importance of preserving heritage for the future. If, as Benjamin Franklin once said, “An investment in knowledge yields the best interest,” then an investment in cultural heritage cannot yield any less, as it shows us at our best, for all time.

The arts, indeed, are another treasure trove of spiritual resources needing constant care and replenishment. This long, historic, and mutually beneficial partnership between our central bank and the arts sector makes that reality physically manifest, and we can only hope that it will continue even more strongly in the decades to come.

Tastefully photographed and designed by Willie de Vera and produced by Bloombooks (the publishing arm of Erehwon Arts Corporation), Kaban is a treasure on its own, and is available for sale to the public at the BSP.