Penman for Sunday, November 23, 2025

IT WAS with great sadness and regret that I received the news of Rosa Rosal’s passing last week—sadness, because of what everyone who knew her and her work would have seen as the end of an extraordinary life of artistry and service; and regret, because I had completed her biography fifteen years ago, and it came this close to publication before being shelved, for reasons I can no longer remember. I think Rosa said she needed to look into it a bit more, but never came around to doing so, until the months became years, and we eventually lost touch.

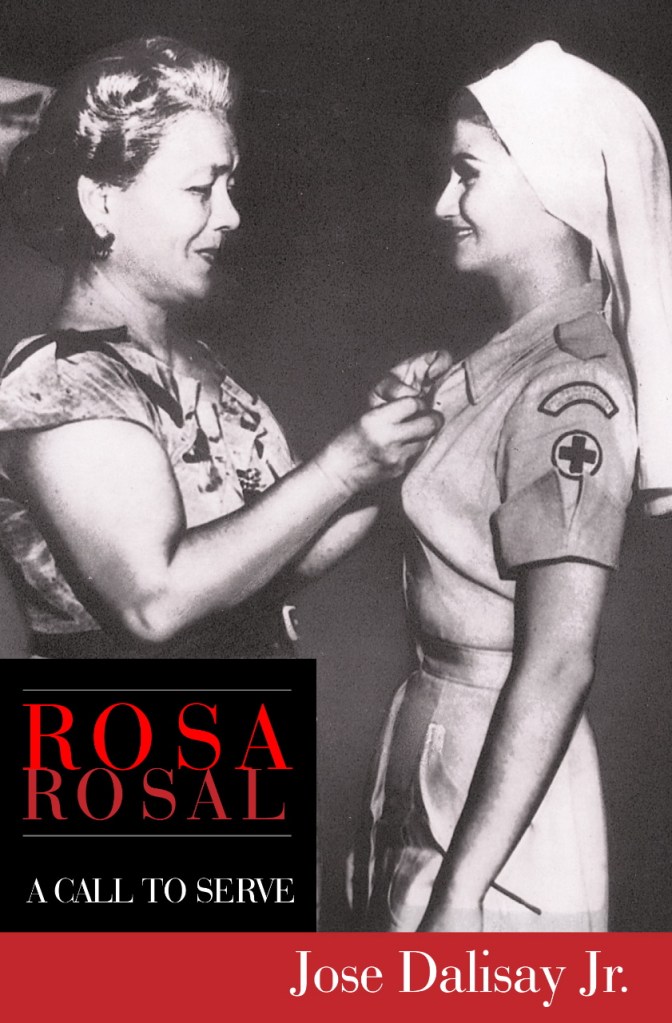

The book had been commissioned by the Philippine Red Cross, the organization to which Rosa had devoted much of her life’s work away from the cameras. Having established herself as one of the country’s biggest movie stars—and not just a star, either, but a truly talented and accomplished actress—Rosa decided to put her celebrity to good use by aligning herself with the Red Cross, its blood donation drives, and other humanitarian efforts she pursued on her public-service programs.

It’s a pity the book (Rosa herself chose the title: A Call to Serve) never came out because Rosa’s life story was a stirring and remarkable one, centered on a woman vastly different from her onscreen persona and yet filled with such drama that it would be hard to believe as a movie. Her life seemed a constant pairing of triumph and tragedy, of maintaining courage and composure in the depths of pain and despair. Toward the end—she was already in her eighties then, and prepared to face her Maker—she left everything to God, being the person of faith that she was all her life.

I recovered the manuscript from my files, hoping that with Rosa’s passing, the Red Cross and Rosa’s family might decide to revisit the project and bring it to being—we owe it to Rosa and all she did. Herewith, some excerpts from the book that might yet be:

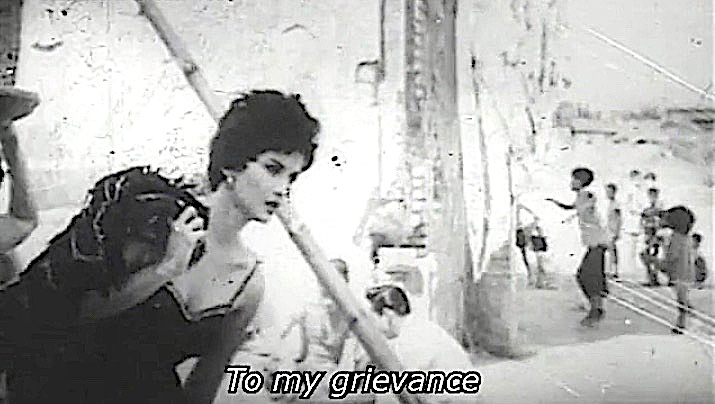

In retrospect, the opening sequence of Anak Dalita (LVN Pictures, 1956) captured what its star, Rosa Rosal, would be doing for the rest of her life: bringing comfort to the afflicted, as unlikely as her appearance and position may have been for an angel of mercy.

In that prizewinning film, set in the war-torn ruins of Manila’s Walled City, Rosa’s bargirl-character Cita steps into the frame in a black, spaghetti-strapped dress, almost ethereally beautiful and glamorous amid such squalid surroundings. It is daytime and she seems to have worked all night, but her first concern is to seek out a dying woman whose soldier-son has been stationed abroad.

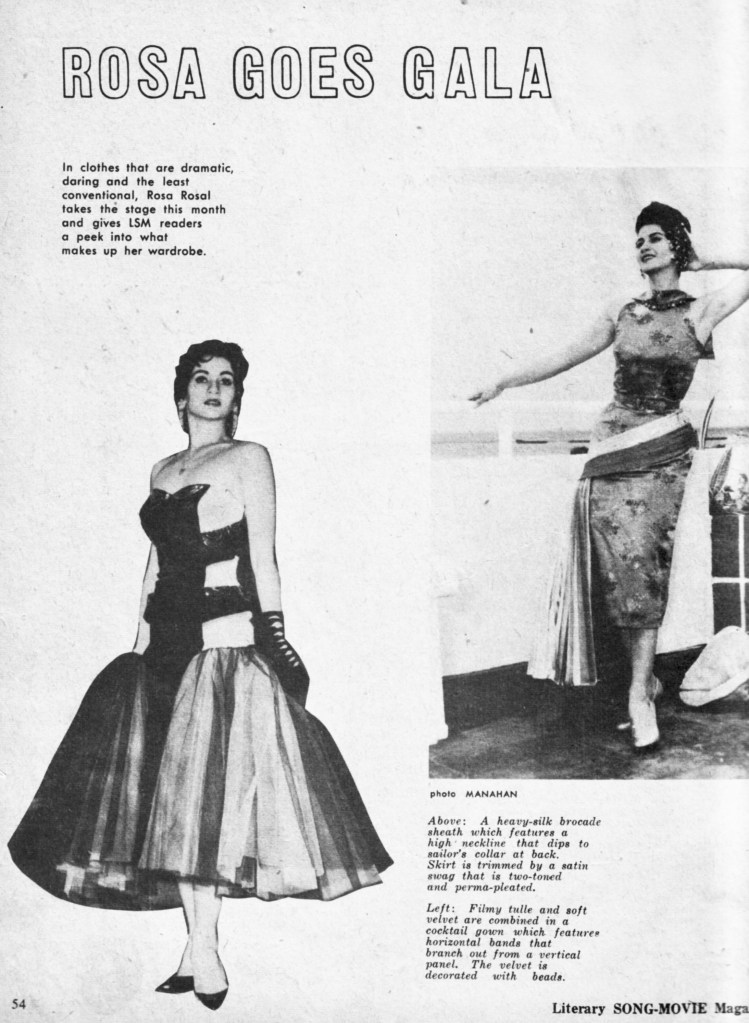

The beauty and the glamour were genuine, and vintage, vampish Rosa Rosal. But just as real, offscreen, was the compassion that animated her in a long and still continuing life of virtue and public service. Rosa Rosal was as lustrous a star as stars came, but her feet remained on bare and solid earth; over the decades, it was the star within her that shone even more brightly than her on-camera celebrity.

The woman who would be known as the Florence Nightingale of her country was, fittingly enough, born with that name. Rosal Rosal was born Florence Danon on October 16, 1931 to Julio Danon and Gloria Lansang del Barrio.

Very little is known of Julio, a French-Egyptian-Jewish businessman. “My father died when I was very young, so I never got to know him,” Rosa says. It was her mother whom Rosa grew up with and looked up to. “She was a simple woman from Sta. Rita, Pampanga, a typical Kapampangan—a great cook, and very industrious. The wisdom she gave me is what made me who I am now. It’s a great thing that I chose to listen to her words instead of resenting her constant presence.”

When Rosa was six, Gloria remarried a Filipino named Ruperto del Barrio; they would have four more children—boy-and-girl twins, and then two more girls. “We weren’t rich, but we lived a decent life thanks to my mother and stepfather’s efforts. They bartered with people from the province. My mother was such a hard worker. She used to sand down all our furniture with is-is, a rough-textured leaf.”

The family lived in a two-story house in Sta. Cruz, Manila. Theirs was a simple, unassuming life, where time spent with one another was highly valued. “My mother made sure that the whole family ate together, so everyone could talk to each other and share stories. We spoke Tagalog in our house.”

Rosa went to the Antonio Regidor Elementary School. Early on, a lifelong trait of hers would surface here. Rosa saw herself as a “strong person,” but instead of using that strength to get ahead of others, Rosa used it to protect the weak. “When I was 10 years old, there was this girl who kept on bullying one of our other classmates. At first I tried talking to her,” Rosa recalls. “I begged her not to cause any more trouble for anyone. But she ignored my request. So one time, when the two of us were in the girls’ restroom, I dunked her face into the toilet bowl. She begged me to stop, but I made her promise not to bully anyone anymore before I did.”

On screen, Rosa continued to do what would have made most Filipino mothers faint. She seemed to think nothing of doing kissing scenes, wearing figure-hugging bathing suits, and playing the other woman. She was the character people loved to hate, but were also secretly entranced by, because she did freely what they could not.

In private, however, Rosa was anything but that kind of woman. She was deeply religious and devoted to her family, and her main objective was to give herself and her siblings a proper education. “Unlike my colleagues, I wasn’t too fond of going out and socializing. I didn’t frequent clubs or places like that. It was only later on that I formed friendships with my fellow actors, like Delia Razon. Actually most of the people that I hung out with were men, and everyone else thought of me as one of the boys. When we went out on the field I had my own accommodations, but I still preferred to sleep and hang out where the crew stayed.”

Oscar Miranda bore witness to the other Rosa: “In our neighborhood, Rosa was admired. Even when she was already a star seemingly beyond our reach, she had a nice smile and a kind word for everyone. In spite of her growing contravida image, everyone knew she was a nice girl, a good girl who was respectful and devoted to her parents, a very pious girl who heard mass every Sunday. Everyone sensed that her new image was just for show and Rosa was their star. Because the neighborhood saw her grow up, she was really one of them.”

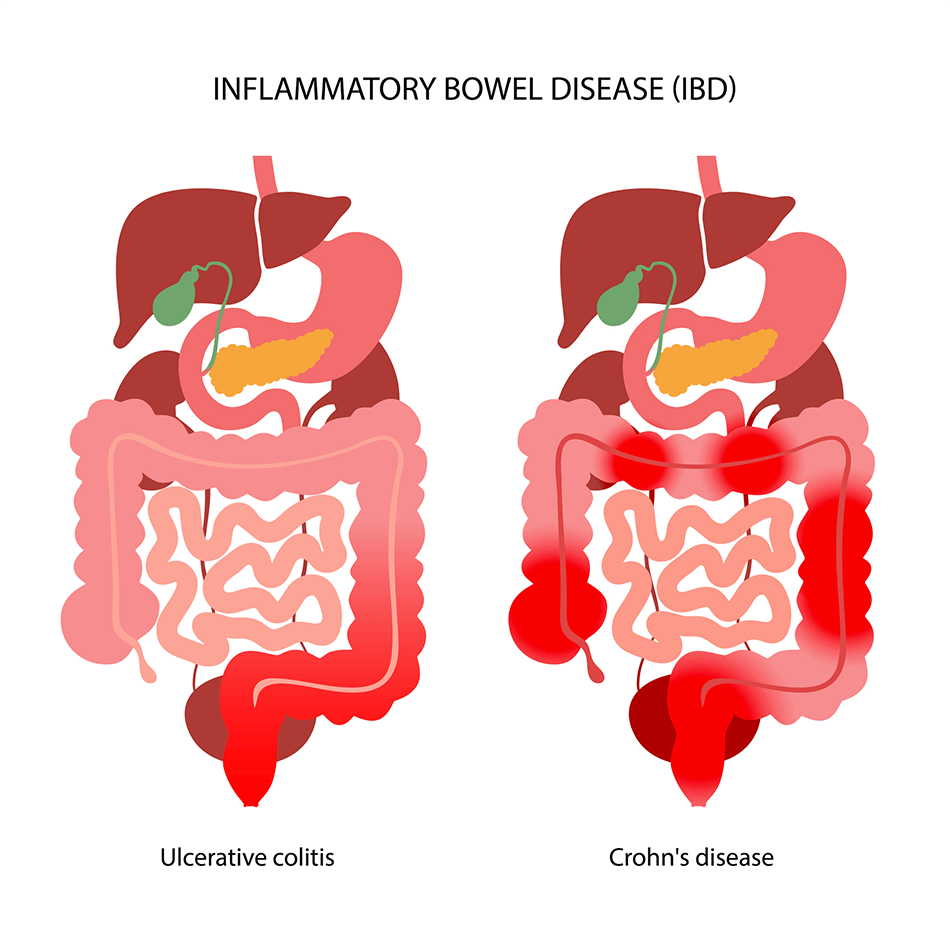

“One time there was this girl at the PGH ER who had fallen from the top of a five-story building, and was in a coma. I returned to the hospital two days later and the girl was still there. I couldn’t help but ask around about her. I was told that the child needed a neurologist, so I talked to Dr. Vic Reyes, a good friend, and had him look at the child. The doctor said that it was a hemorrhage and that the girl needed blood. So I went to the Red Cross, got some blood for the girl and brought it back to the hospital. Even with the blood, the doctors were not sure if the child would make it. The mother was there, crying the whole time.

“When the blood was about to run out, the girl’s hands suddenly moved. Her eyes opened, and she cried out, ‘Mama!’ and the mother cried again, this time in relief. So with that experience I saw first-hand what blood can do. I realized that blood is something very precious. It can really prolong someone’s life. That’s when I decided to dedicate myself to the Red Cross,” Rosa recalls.

Even before this, Rosa had already attended blood donations through the Red Cross. “At the time, before you were accepted as a Red Cross member, you had to undergo training. I would come home from shooting at 5 am and then go straight to the training at 7. I didn’t have a car then so I had to take a cab to the Red Cross.”

The Red Cross and its blood bank would become so important to Rosa that they would eventually become the focus of her life, well beyond the movies. “You know I don’t celebrate my real birthday. I celebrate July 4,1950, the date of the first blood donation drive that I organized. It was held in Muntinlupa. I used to personally deliver blood to hospitals in Subic. On one such delivery run, a group of Huks—Communist guerrillas—stopped me in Pampanga. They told me that the next time I passed by, I should attach a Red Cross banner to my car so they would know that it was me.”

There was a tragic background to that encounter with the Huks. She had become friends with Baby Quezon, President Manuel Quezon’s daughter. “The two of us would meet at the Army-Navy Club. One day, I had just made a personal appearance, and they were asking me to hang out with them. Normally I couldn’t say no to Baby, but my mother was waiting for me at home. On the way home, I was with Alfonso Carvajal, and we heard on the radio that Baby and her friends had been ambushed by the Huks, and they were all killed. When I got home I told my mother what happened. I realized that my love for my mother saved my life.”

Working for the Red Cross also began to change how Rosa might have wanted others to see her. “When I became a regular volunteer for the Red Cross, I requested Manny de Leon if I could veer away from contravidaroles. I was tired of playing one, anyway. So he gave me Sonny Boy, opposite Jaime de la Rosa, and I won a FAMAS award for that.”

* * * * *

Not everyone appreciated Rosa’s efforts. Some suspected her of hypocrisy, of using her social work to promote herself. One incident is embedded in Rosa’s memory. “One time a group of teachers wanted to raise money to build a school in Tondo. I was able to raise P10,000 and I gave it to them. I was about to go home from Tondo when I noticed that one of my car’s tires was flat—the tire had been slashed. A man stepped up to me and said that he was the one who did that to my car. He said that I was doing all of my volunteer work not because I wanted to help people but because I wanted to sustain my popularity as an actress. The teachers helped me fix my car and told me to ignore the man, but I was still affected, and I cried on the way home. My mother saw me and I told her what happened. She didn’t tell me to stop doing charity work. She just sat with me and comforted me.”

Years later she would meet this man again—a girl was badly in need of a blood transfusion, and Rosa provided the help she needed. A man who identified himself as her father approached Rosa in tears, begging her forgiveness. “I was the one who slashed your tires,” he confessed. “I’m so sorry I doubted you!” Rosa wept with him, astounded by the irony of the situation.

* * * * *

That part of the country—Batangas, Cavite, Laguna—lived up to its reputation as a hotbed of rebellion and outright banditry. Steeped in poverty, people resorted to desperate acts; the comforts and glamour of Manila were another world away, and the only contact that the provincial folk had with it was through the movies—or, better yet, on those rare occasions when the movie stars themselves deigned to make a personal appearance in the boonies, usually in conjunction with a town fiesta, of which their ethereal visitation became the highlight.

And so did Rosa find herself again, another time, on another bus in Batangas, coming home from an appearance with an entourage of about 20 actors, singers, and dancers. Suddenly the bus was stopped in the middle of the road by a gang of robbers. “There were about ten of them,” Rosa remembers. “They boarded our bus and asked for our belongings. I told everyone to just comply. The thieves heard my voice and thought that I sounded familiar. To be sure, they asked me who I was, and I said I was Rosa Rosal. ‘Aren’t you the one with the Red Cross?’, one of them said. I said yes, and to everyone’s great surprise their leader ordered his gang to return what they stole. “Return everything. Don’t touch her, because she helps people like us.’ And then they left. We all cried afterwards. It was quite an experience. But I didn’t tell my mother about it.”

I wish I could share more—we’ve barely scratched the drama of her real life—but the rest will have to wait for the book. Let me end with something Rosa wrote in her preface (with a reference to her beloved grandson James, who died in an accident in 2010):

“I am ready to go anytime that He calls for me. I know that when that time comes, Jesus, my mother, and James will be there to welcome me. I can imagine the smile on their faces when God shows me the permanent home He has prepared for me. I thank Him for all the awards He has given me. I praise Him for the death of my grandson, James, as well as the 30 years of suffering of my mother. We praise God not just for the good times but also for the painful times. I have gladness and joy in my heart as I have obeyed His commandments and I answered His call to serve.”