Penman for Monday, August 26, 2013

Penman for Monday, August 26, 2013

A FEW months ago, I was thrilled to read the news that TS Eliot’s pen had been lodged with the Royal Society of Literature, replacing a quill pen that had been owned by Charles Dickens and used by the society’s fellows to sign themselves into the exclusive club. Now based in Somerset House in London, the society counts some 500 fellows among its members, and not surprisingly these have included some of British literature’s most illustrious names both ancient and modern, from Yeats to Rowling. (Fourteen new fellows can be elected to the society every year; they need to have published at least two outstanding books and gained the acclaim of their peers.)

The story, according to The Guardian, was that Dickens’ quill pen had understandably lost its sharpness, and that a replacement was therefore in order (members can also choose to use Lord Byron’s pen, reportedly still in fine shape). Eliot’s widow (his second, actually) Valerie had just died in 2012 and had willed his pen to the RSL, making the turnover possible. (Before we leave the subject of quill pens altogether, let me note that these medieval tools took a lot more to make than pulling big feathers from the butts of geese, including tempering in hot sand and sharpening with what came to be logically known as a pen knife.)

It took some Googling before I found a picture of Eliot’s pen, which was never identified in the news stories (picture above courtesy of The Telegraph). From what I knew of vintage pens, it was a Waterman in black hard rubber with two wide gold bands, on one of which was inscribed Thomas Stearns Eliot’s initials. It had been a gift from his mother Charlotte; Eliot had moved to England from the US in 1914 when he was 25, so the pen, which dates to that period or a little earlier, might have been a parting gift.

I remembered Eliot’s pen over last week’s rains when, with nothing much else to do at home (that’s not quite right—I always have something to write, but am a horrible procrastinator), I took out my pens for a ritual rubdown and came across a few I hadn’t seen in a long time. That was because these were special pens kept in a special corner—pens donated to my collection by writer-friends, pens they had actually used in their work. Over the years, as word got around of my fascination with fountain pens, generous friends and patrons like Don Jaime Zobel de Ayala and Wash SyCip have gifted me with lovely pens, which I continue to treasure.But the pens I’ve assiduously run after have been those of my fellow writers, especially older friends who started writing with them in the pre-computer age.

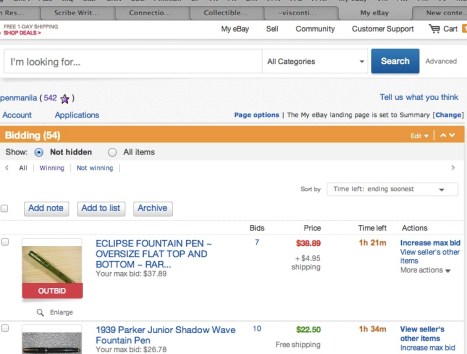

My little writers’ corner now includes pens from National Artists Franz Arcellana, NVM Gonzalez, and Virgilio Almario, as well as from dear friends and colleagues Doreen Fernandez, Jimmy Abad, and Jing Hidalgo. They range in kind from a Parker 51 from Franz and a Montblanc 220 from Doreen to well-used ballpoints from NVM and Rio. (I’m still hoping, one of these days, to be able to ask for pens from Bien Lumbera, Frankie Jose, the late Tiempos, and Greg Brillantes, among others.) Needless to say, these pens will never be sold on eBay. If and when we open a Writers’ Museum, or at least a permanent display like they have at the National Library of Singapore, I might consider loaning or passing them on, but for now they’ll stay with me in my man-cave, feeding my fetishist longings alongside books signed by Nick Joaquin, Jose, Brillantes, Bienvenido Santos, JM Coetzee, Frank McCourt, Kazuo Ishiguro, Junot Diaz, and Edward Jones. (Some of these—the non-Filipino ones, excepting Junot’s—I wouldn’t mind putting on the block someday.)

Before typewriters and word processors made everybody’s writing look like everybody else’s, writers and their pens enjoyed a special relationship, some more so than others.

Mark Twain, a friend to Filipinos in his staunch opposition to American imperialism, preferred the Conklin Crescent Filler, a pen that used an inverted half-moon of gold to press down on the rubber sac in the barrel to release ink. It was a very popular filling system in its time and Twain became something of a poster boy for Conklin, so when the company was recently revived (like so many other long-dormant pen makers, on the heels of a neo-traditionalist trend boosting fountain pen sales), it named its flagship pen what else but the Mark Twain.

But Twain’s popularity never came close to that of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was reported to have used a Conway Stewart—a venerable British brand recently revived—through the dark days of the war. So formidable a figure was Churchill that not only Conway Stewart but Montblanc and Onoto have also come out with pens in his honor.

Onoto—another British pen maker, associated with Thomas de la Rue which used to print our banknotes in the pre-BSP days—also claimed Sir Winnie among its famous users. In the age before paid celebrity endorsements, catching someone popular using your product was good as an endorsement, and was free besides. The minders of today’s Onoto have come up with incontrovertible proof—a letter sent by the young Churchill in November 1915 to his wife Clementine from the trenches in France, where he talks about “the venomous whining and whirring of the bullets which pass overhead.” But the clincher for the company was the ending: “Send me also a new Onoto pen. I have stupidly lost mine.”)

Speaking of the French, Fountain Pens: History and Design quotes the French theorist Roland Barthes waxing ecstatic over his pens: “In the end, I always come back to fountain pens. The important thing is that they can ensure the graceful handwriting I care so much about…. I have too many fountain pens and don’t know what to do with them. Yet, as soon as I see one, I can never resist buying it.”

There’s probably no more famous user of a fountain pen today than Neil Gaiman, who employs quite a range of them, from among the 40 to 50 he reputedly owns—a TWSBI, a Pilot, a Lepine, a Delta, and a Visconti, among others—not just to sign books but to actually write his novels with. He lives, he says, in “a house full of Macs” and is a self-confessed iPod freak, but he told the BBC that, with pens, “I found myself enjoying writing more slowly and liked the way I had to think through sentences differently. I discovered I loved the fact that handwriting forces you to do a second draft, rather than just tidying up and deleting bits on a computer. I also discovered I enjoy the tactile buzz of the ritual involved in filling the pens with ink.”

Pen addicts (the fancy name is “stylophiles”) can never have just one pen to use, so we prefer to talk about “the rotation,” that merry-go-round of favorites we keep constantly inked and polished, ready to be taken for a ride. There’s a lot of debate in the group over whether one should carry one’s most precious pens; I’m of the school that believes that life is short and runs ever shorter, so that fine pens, like Rolexes and Patek Philippes, should be carried with pride and reasonable care. I can’t tell you how many pens I’ve lost in my practice of this carpe diem philosophy, but I have no regrets.

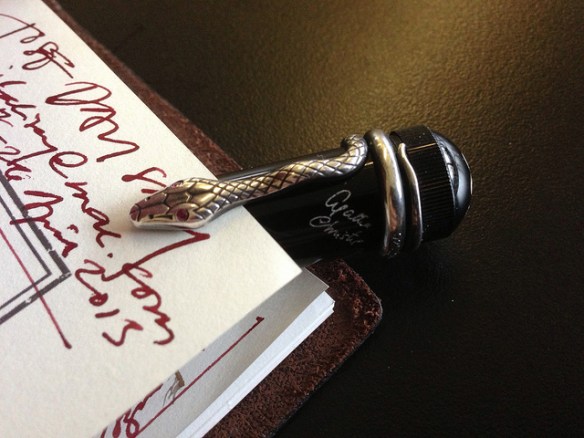

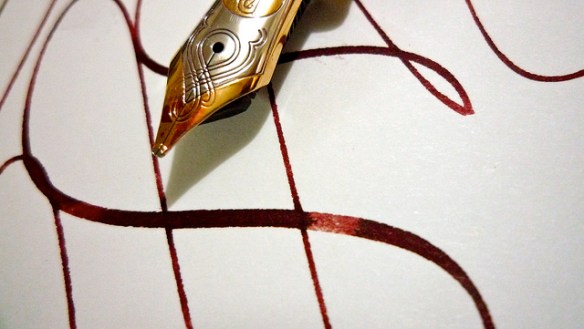

These days, my most faithful pocket companion and favored pen in hand is a 20-year-old Agatha Christie, a largish black pen with a clip in the form of a sinuous snake, a tribute to its exalted namesake and her penchant for mystery. This gorgeous pen has written nothing more noteworthy than, well, notes, but having it in my pocket puts a lift in my step, and even doodling with it puts me in a trance, poised as it were to write until its cache of ink (either Rohrer and Klingner Sepia or Diamine Oxblood) runs dry.

In these digital times, of course, hardly anyone except Neil Gaiman really writes stories and novels with a pen anymore, and even this piece is being written on a MacBook Air, which is threatening to croak any minute now for want of juice. That was the beauty of the pen, a writing instrument you could pop into your pocket and pull out as the inspiration or necessity struck you, batteries and brownouts be damned. I’m sure that Tom, Mark, Winnie, Roland, and Neil would wholeheartedly agree.

Penman for Monday, January 14, 2013

Penman for Monday, January 14, 2013