Qwertyman for Monday, July 29, 2024

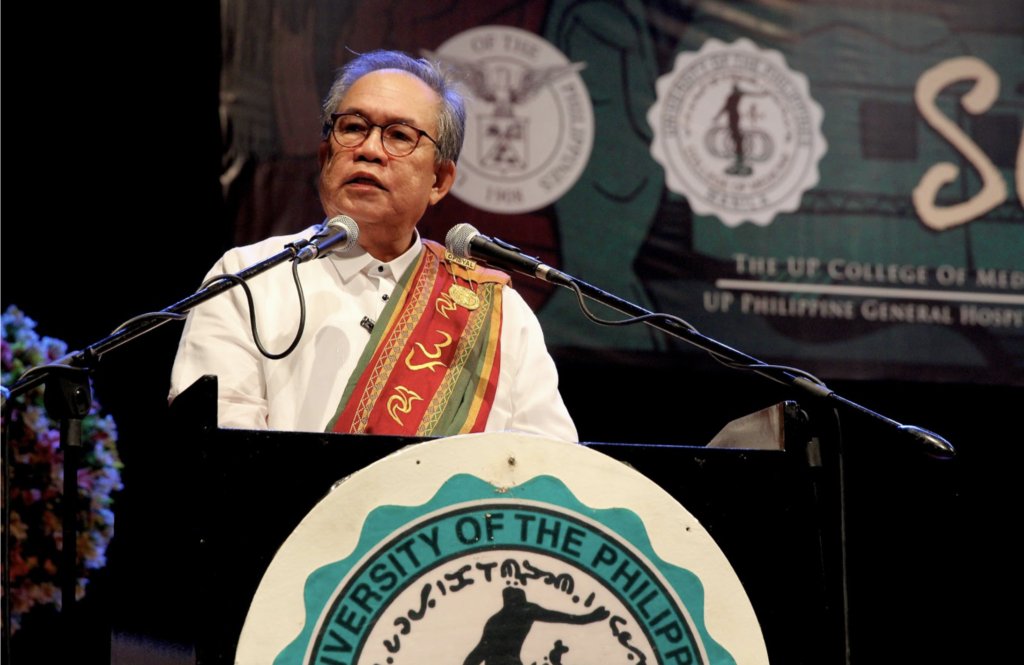

(This is the full text of the shortened version published in my column for today of my commencement address to the graduating class of the University of the Philippines Diliman Extension Program in Olongapo and Pampanga on July 26, 2024.)

A VERY pleasant afternoon, and my warmest congratulations first of all to our graduates and their parents today. Thank you for inviting me to come over today to share some of this old man’s thoughts with you.

I have given commencement speeches at UP graduations before—twice at UP Baguio, once at the UPD College of Science, and then at UPM’s College of Medicine—so you would think that I would take this assignment in stride and just repeat what I told the others, but no.

This is probably the smallest and most intimate of all UP graduations I have attended, for which reason I thought I would do something different, something special, and write something new, this short talk I’ve titled “The Knowing Is in the Living.”

Now, as nice as our young graduates are, they’re probably thinking, “Oh, no, they invited another of those tiresome old Boomers who’ll be telling us things that we already have coming out of our ears. Things like, how hard and difficult life was for them, walking to school in the sun or taking notes by hand and we have it easy, so we should stop bitching about slow wi-fi and weak aircon and toughen up.

“He’ll talk about how socially aware and politically committed they were, how they cut classes to march in the streets and fight the dictatorship, going underground, getting caught and tortured in martial-law prison while watching friends die in heroic battles with fascist forces—while we argue about the characters in House of the Dragon over cappuccino at Starbucks.

“He’ll wax nostalgic about fountain pens and typewriters, index cards and pencil sharpeners, about inhaling the dust in the library stacks and paying fines for overdue books, while we’ve become overly dependent on Google and that new monster, AI, which can do in seconds what took him weeks to produce. He’ll talk about integrity like he invented the word, about refusing to compromise no matter what.

“He’ll tell us to learn to live in monastic simplicity, in denial of today’s comforts and conveniences and the allure of the coming iPhone 16. In other words, he’ll do his best to make us feel like we were born in the wrong decade, that we missed out on the great defining and character-building struggles of the past—World War II, martial law, EDSA (and no, Covid doesn’t count)—and that we’re lost souls floating in some kind of existential limbo, with little substance and without purpose.”

Well—did I tell you any of that? Do I look like the kind of commencement speaker who would inflict his wisdom—otherwise known as pain and anguish—on his captive audience for the next half-hour, in revenge for all the predictable and long-winded speeches he himself had to listen to all his life?

Before you smile too broadly, let me remind you that I’m still in command of this podium and could do just that, just for the fun of it—but I probably won’t. And I won’t, because the opportunity is just too great and too inviting to be different, to say something you will actually remember and maybe even cherish for the rest of your life.

Ordinarily, on an occasion like this, I would have spoken to you about the topics I usually take up in my columns for the Star—about how important it is to match intelligence with values, about the need to seek out the truth in this age of fake news and AI, about how deftly but resolutely we should navigate the murky political waters ahead of us; in other words, about how we must develop a strong and clear moral core, whatever profession we choose, and live for the good of others.

But again that’s the kind of message that AI itself could have written, fed with the prompt “Write me a graduation speech for the University of the Philippines.”

I will trust that you already know these things. I will not speak about your degrees and what they will mean to the nation, which surely will be substantial. I will not even say how important UP is to the Filipino people; you already knew that when you took the UPCAT, which was why you took the UPCAT.

Instead, today I will talk to you about time—yes, that fourth dimension which, according to science and philosophy, is really a function or a measure of change. Without change, there is no time.

Why time? Because it’s been on my mind a lot lately. Last January, I celebrated my 70th birthday and my 50thwedding anniversary with my wife June. I was deeply grateful for those milestones, which I honestly never expected to reach, having been a young activist who went to martial-law prison and who saw many of his friends die too soon. So for me, anything beyond 20 was what you would call in music a “grace note,” an unexpected bonus that has just kept on giving and giving.

To be sure, it hasn’t always been an easy life, and I won’t bother you with the details, but I can tell you what a huge surprise and relief it is to be here, alive and reasonably well, at 70. I am now older than my professors were when I was your age, and the reversal is both fascinating and, for you on the other end of it now, a mystery yet to be written.

For most of us, life has a fairly predictable plot, and it goes this way:

In your twenties you will want to know who you are, what you stand for. You will choose a course and a profession, get a job, dress up like an adult.

In your thirties you will think more seriously about companionship, maybe marriage, maybe children. You will want your heart to make up its dizzy mind, and settle on someone, or get used to being alone.

In your forties you will fret about finances, your position in your company, maybe have an affair, lose your faith, and then again if you’re lucky maybe gain everything back.

In your fifties you will be expert at many things, sit on boards and manage this and that. You will begin to think about words like “stability,” “reputation,” and “legacy.”

In your sixties your steps will become shorter and slower, and you will want comfort most of all—a soft bed, an easy chair, good food and wine—and indulge your bucket list.

In your seventies and eighties, you will just want and fight to be alive.

In your nineties, with most of your friends gone, and with your eyesight and hearing going, you may well just want to be dead.

That’s the basic plot—but like time itself, it’s not a fixed one. Time is strangely flexible.

In my writing classes, I often say that a well-written story, even if it’s twenty pages long, feels like it ended too swiftly, but a badly written one, no matter how short, feels like forever. And we all know but don’t understand why happiness always seems to be fleeting, while grief and pain endure. That’s how time is bent by whatever we fill it up with—how it holds meaning, or loses it.

How will you fill up that space with change, and make your time worthwhile? What kind of story will your life be?

As one of my book titles go, “The Knowing Is in the Writing.” By this I mean that we writers think that we know our characters from the beginning—but in fact, we only really know them as we write about them, and subject them to the kind of intense pressure that life will bring to bear on each one of you.

Let’s say, for example, that Tony is a young lawyer, smart and idealistic, determined to seek justice and freedom for his people, destined for professional success. He works for an NGO for not much money. He is engaged to Marie, a PGH nurse who’s also supporting her family, and who has been offered a job in the UK. Tony doesn’t want Marie to go, because she will be away for many years and he wants them to marry, but he can’t support them both and their families as well on his salary. Tony is then recruited by a big real estate firm to work in its legal division, where he will help in the removal of squatters from company property and the conversion of farms into subdivisions. What will Tony do?

How well do we know Tony, until he actually makes a moral choice that could possibly run against the character we thought we knew?

In fiction and in playwriting, I often point out to my students that characters become most interesting when they go out of character—not whimsically, but out of dramatic necessity and inevitability, the kind of tortured inner logic that drives us to do things we never thought we could, in our imagination of ourselves as good people: to lie, to cheat, to steal, to support extrajudicial killing, to laugh at rape jokes, and to think that someone who habitually lies and brings out the worst in people can be fit to be president. But conversely, that turn of character can also lead us to perform amazing acts of nobility and charity, of heroism.

In your case, the knowing will be in the living. You think you know yourself today, what you want, where you want to go, and how to get there—and it’s important that even now, you have this game plan and this compass to lead you forward. But you will never know and discover your true self until your most vulnerable moment, at which your soul will be revealed in utter transparency.

For some of us, the sad truth is that life will be short. But that’s no reason to say it will be worth little, because you can still make it meaningful and memorable. Remember Achilles, who in the Iliad was given a choice of living a short but glorious life, as opposed to a long but boring one; he chose the former, and thereby became a legend. And there was the brilliant modernist writer Djuna Barnes, who lived to be 90. Taking off from that famous quotation from Thomas Hobbes, she said that “For others, life can be nasty, brutish, and short. For me, it has simply been nasty and brutish.”

But again, how your lives turn out will be your story to write, although you will have many co-authors, including the Divine. Some say life is predestined, which would make for bad fiction; I prefer to believe in at least the illusion of free will, of human agency, because then we and our fictional characters have moral responsibility; and in such stories of inner struggle, there will be lessons to be learned, like the Greeks learned from the plays they watched over and over again.

Life will be a challenge, as soon as you step out of this campus into the world at large. But what I can tell you is that, with grit and a little luck, you will survive. To do that, you may have to learn to forgive yourself for your mistakes, to change your mind, and to compromise if you must, because the ideal you will always be a work in progress. Whoever sits in Malacañang or the White House, you can still find ways to serve the people, for which you will and must survive. We survived martial law; you survived the pandemic. Surely we can give purpose to our good fortune. In my case, I have found that purpose in my writing, in my search for truth and beauty, and in my more modest and focused commitments to my family and community.

So, again, how shall we fill up the time ahead of us? Of course we’re running on different clocks or even calendars. If your life is at brunch, mine has just been called to dinner. I don’t know about you, but I will have that dinner with my wife on the beach, with a glass of wine, imagining what it must be like over the deepening horizon.

That horizon will always be ahead of us. We think we are forging ahead into the future, but in fact, with every breath we take, we are becoming part of the past, of what happened, of what was. When I hold and look at the silly old things I collect—three-hundred year-old books, and old fountain pens and typewriters from when Jose Rizal was still alive—I am comforted by the certainty that the past survives in artifacts and memories, so that it is important that we leave images and signatures that will bring smiles to those who see them.

There is an afterlife. In the very least, it is the life of those we leave behind. You will now be part of my afterlife. Through this speech, through my words, I will live in you.

Let me end with a quote from a favorite source—me—and share something that I have said to every UP graduating class I have been honored to address:

To be a UP student, faculty member, and alumnus is to be burdened but also ennobled by a unique mission—not just the mission of serving the people, which is in itself not unique, and which is also reflected, for example, in the Atenean concept of being a “man for others.” Rather, to my mind, our mission is to lead and to be led by reason—by independent, scientific, and secular reason, rather than by politicians, priests, shamans, bankers, or generals.

You are UP because you can think and speak for yourselves, by your own wits and on your own two feet, and you can do so no matter what the rest of the people in the room may be thinking. You are UP because no one can tell you to shut up, if you have something sensible and vital to say. You are UP because you dread not the poverty of material comforts but the poverty of the mind. And you are UP because you care about something as abstract and sometimes as treacherous as the idea of “nation”, even if it kills you.

Sometimes, long after UP, we forget these things and become just like everybody else; I certainly have. Even so, I suspect that that forgetfulness is laced with guilt—the guilt of knowing that you were, and could yet become, somebody better. And you cannot even argue that you did not know, because today, I just told you so.