Qwertyman for Monday, May 12, 2025

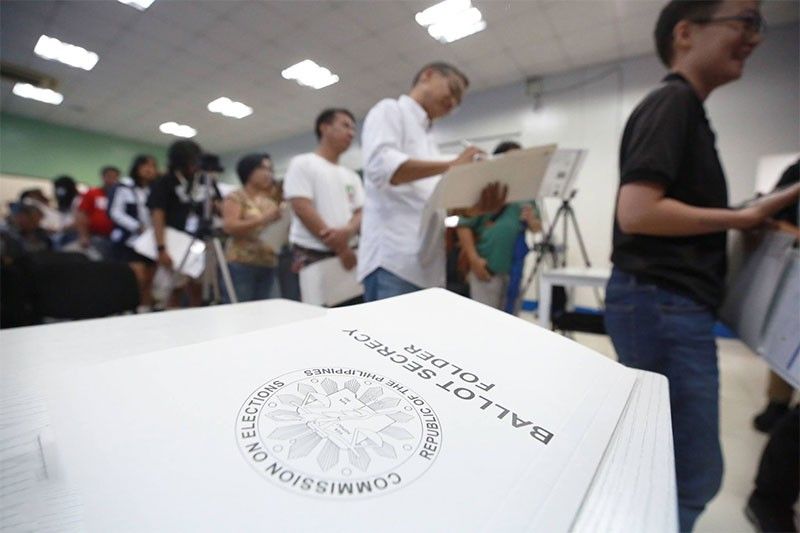

TODAY, ONCE again, we troop to the polling booths in the hope of making our votes matter—votes that, if the cynics are to be believed, might as well be dust in the wind. The surveys have spoken, the winners named. All that remains is for this day to be over, for the formalities to be done with, for the supposedly inevitable to play itself out. And then we’ll watch the new-old Senators of the Republic proclaimed in a ceremony that will showcase the state of our electoral mind.

As absurd as it may seem, many Pinoys will actually be happy with the outcome—that’s what the surveys are all about, aren’t they? These are the senators we wanted—or most of us, anyway. “Most of them” is probably what you’re thinking, if you’re a regular reader of this column and agree with most of my views.

I can’t think of a more complicated election in recent times, in terms of an answer to the question of “What’s in our best interest as Filipinos, and how do we make that happen?”

The idealist in me has the simplest and probably the morally most unambiguous response: vote for the best candidates, period: the intelligent, the progressive, the principled, the proven, the humane, the hardworking, the uncompromised. Whether they win or lose, it shouldn’t matter—you’ve done your best as a responsible citizen; in a sense, you’ve won. I sorely want to believe this, and to do this today.

But persistently, impishly, like a little devil perched on my shoulder, a contrarian spirit urges me to temper my idealism with some consideration of its practical costs.

Last week in California, a Fil-Am friend asked me to explain the significance of these elections. In the US, midterms usually mean a referendum on the incumbent President’s performance, and next year will most definitely be one for the Orange Pope and his systematic dismantling of American democracy.

For us Filipinos, May 2025 isn’t that clear-cut—although it should have been, if the armies of May 2022 had remained in place, leaving us with a stark choice between the good and the bad.

But the ruling “Uniteam” alliance has since collapsed, with each side fielding its own troubled slate of aspirants, all seething with the most primal of motives: survival, revenge, profit, and opportunity.

The opposition seems to be a loose coalition of liberal, Left, and anti-administration forces. Among these, four names have consistently surged to the top in the kind of social media neighborhood I inhabit. I’ll call them my Triple A candidates, the ones I won’t have any second thoughts about, leaving me with eight more spots to fill.

It’s those eight that give me pause—not for any lack of qualified and virtuous prospects, but because there could be dire consequences for not filling up the rest of my ballot, as some have suggested, or voting for names without a prayer of winning, as a matter of principle (or, by this time, by force of habit).

It’s interesting to observe how, unlike in previous elections where voting straight for a party’s slate was the norm, various formulas and menus have emerged on social media—cafeteria or halo-halo style—to reflect this urge for some balance between the ideal and the practical in this three-cornered fight. Even opposition stalwarts, including Leni Robredo herself, have been excoriated for their previously unthinkable endorsements of certain candidates from the other side. Whatever happened to ideological purity? (It was always an illusion: note the Left’s earlier alliances with a notoriously bloodthirsty Digong Duterte and an unabashedly capitalist Manny Villar.)

I think many Filipinos understand what’s at stake in this election—not just who will compose the next Senate, but what that composition will mean. As I told my Fil-Am friend, Rodrigo Duterte may be safely imprisoned in the Netherlands, but his specter looms large and heavy over these midterms, through his proxies led by his daughter, VP Sara and their “DuterTEN” team (now more like DuterTWELVE, if you add one Marcos and one Villar). Sara was all set to be impeached for grave threats against the First Family and grand theft Piattos—which would not only have taken her out as VP but disqualified her from running for President in 2028. But that procedure—needing at least 16 votes in the Senate—got kicked down the road, after the election, leaving Sara’s fate up to the newly reconstituted Senate to seal.

So again, I told my friend, presuming that the BBM administration’s game plan here is to freeze Sara out of the presidency so it can install its own man, 2025 is really all about 2028. It’s a referendum, sure—not so much about the present President, but rather the past and maybe the future one. We’re not just—or not even—voting necessarily for the best candidates, but for senators who will push Sara out, or keep her in. Daddy Digong’s summary extradition to the ICC, while a relief for many, merely intensified that drama, raising the stakes to a matter of survival for the Dutertes.

It’s another sad and sorry spot to be in, for these elections to come down to choosing among the lesser or the least of 8, or 16, or 24 evils, against the statistical near-certainty of another wipeout for the truly good. Should I support this fairly familiar trapo, the devil I know, over that manifest idiot, just to help ensure that the latter stays out? Or, again, should I simply disregard all the surveys and scenarios, and vote from my purest and most innocent of hearts for the best people on that ballot? (Was this how the cardinals chose Pope Leo XIV, or did more pragmatic considerations come into play?)

By the time you read this, I shall have cast an early vote as a senior in my barangay. Like we often say, we are whom we vote for, and there’s a part of me that fears what I’ve become or may have to be. I need some of that Holy Spirit with me today—we all will.