Qwertyman for May 29, 2023

THE WORST fire I ever witnessed was that of the Family Clinic hospital near Quiapo in Manila in 1972. I was a police reporter for the Philippines Herald, on the graveyard shift at the MPD HQ, when the three-alarm alert came in and we sped out in our jeep to the fire. Flames were billowing out of the upper floors and people were on the roof when we got there, and soon, sickest of all, I began to hear the thuds of bodies falling onto the pavement, of those who could no longer bear the heat and chose the only other terminal option. When I called the night editor to tell him what I was looking at, he had an additional assignment for me: “Count up the bodies, we need a figure.” I spent the early morning making the rounds of the nearby hospitals and their morgues, seeing up close what fire can do to a human body, the weeping of burnt flesh. I was eighteen, a college dropout eager to work; that night was worth a year in journalism school for me.

Many decades later, early in the morning of April 1, 2016, I was playing poker with some friends when I got a text message from another night owl that the UP Faculty Center was burning. Ever the skeptic, my first thought was that it was the first of what would be many April Fool’s Day jokes, but then other messages confirmed the terrible news. I dropped my cards and drove back to the campus—where I also live, by the way—behind the blare of firetrucks speeding to the scene of the fire, their loudness and haste almost superfluous in the stillness of the night.

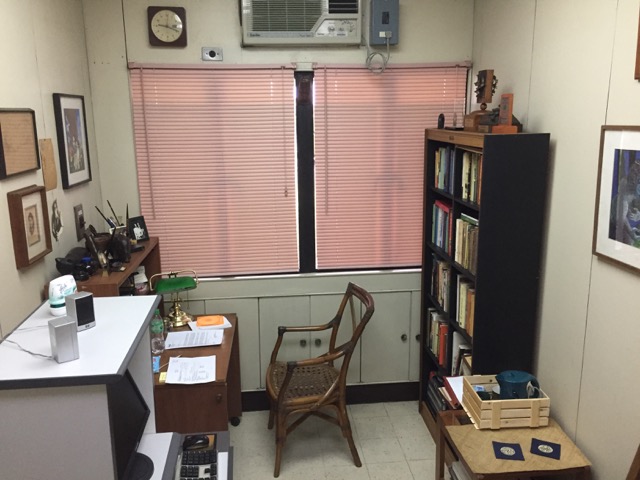

I arrived in time to catch the sight of my office burning—the whole first floor, our whole department, was burning. Strangely at that moment I felt no pain, no sense of loss; I didn’t flail around or throw up my hands in anguish. I suppose that was a form of shock, the way our brain throws a cold, wet blanket around us to insulate us from the heat, to keep us immobilized and therefore safe in the face of catastrophe. Unavoidably my mind began taking inventory of what was in my room—books, paintings, the best student papers of thirty-some years, twenty first-edition copies of my book Penmanship I had saved for its special paper, a computer, flotsam and jetsam from an academic life. There were many precious and irreplaceable pieces in that office, for sure, but again strangely, as soon as I remembered them, I said goodbye; I realized that I was muttering what amounted to a prayer.

Two days later, when the smoke had cleared, I stepped into the gutted building and took a video with my phone. The embers were still steaming beneath my feet. I confirmed with my own eyes the finality of things. Everything but the shards of a ceramic cup was gone—and my book of stories, prettily charred around the pages as though for some theatrical presentation. My writer’s mind was compensating, salvaging scraps of beauty from the crushing loss. That comes to us like second nature; we want to give our grief exquisite form, hoping for meaning and consolation.

There is something about a fire, a compelling majesty, that Filipinos instinctively respond to—not necessarily to help, which is beyond most of us, but to watch and be spellbound by. Where is the child who didn’t jump out of bed and dash into the street at the shouts of “Sunog!”, followed by the festive clangor of alarms and firetrucks? Nighttime fires are especially dramatic, as the sky glows orange and the smoke curls into your nostrils. You are aware that something terrible is happening to someone, and the next morning the news will carry the grim details: a family trapped, a mother curled over her baby, a son who had just graduated the week before. We feel sorry for these victims, while being secretly relieved that we ourselves were spared. Perhaps what attracts us to fire is its anticipation of The End, with science assuring us that the sun will scorch the earth in its last embrace and religion threatening yet more heat for miscreant souls.

When I heard about the fire at the Manila Central Post Office building last week and began seeing the pictures coming online, I reacted with the same stunned silence, trying to absorb the enormity of it all, while morbidly, guiltily, indulging my fascination with fire. It was epic theater—the inferno raging behind and through the neoclassical columns that had withstood a war. I should have been mourning the loss of hand- and typewritten letters—rarities themselves in these days of email—and of other valuables in that building (oh, the stamp collection of the Bureau of Posts!), but my mind drew me back to my childhood, when my father was working at what was then the Department of Public Works, Transportation, and Communications, which was housed in that building.

I must have been just five or six when my dad brought me there to his mezzanine office; I recall rocking on his wooden swivel chair, and playing with the double-tipped red-blue pencils on his desk. At lunch, we crossed an inner courtyard to the cafeteria. My father was just a clerk then, but to me, he seemed like the boss of the place, and I wanted to be like him, seated behind a big table with a pen in hand (in my sixties, I would buy a similar swivel chair).

Editorials will and should be written about the MCPO building’s loss and for its reconstruction. Explosive words like “arson,” “heritage,” “accountability,” and “negligence” will fly up in the air. For a while, like the fire itself, they will consume us, hold us in thrall, until they flicker out and we return to our daily business, our outrage expended.

Once again we find ourselves loving what is gone too late. But perhaps it takes a fire to awaken love and memory, and to teach us important albeit bitter lessons about impermanence, and thus the need to care and to give value while we can. Whether started by accident or by diabolical intent, fires remind us that we are not what we accumulate but what we regret losing, and struggle to rebuild and recover.

(MCPO photo from philstar.com)