Qwertyman for Monday, June 10, 2024

I WAS back last week in the city of Kaohsiung in Taiwan with a group of writers from the University of the Philippines Institute of Creative Writing, at the invitation of Dr. Eing Ming Wu of the Edu-Connect Southeast Asia Association, an education NGO seeking to establish stronger ties between Taiwanese universities and their counterparts south of Taiwan. We were there to meet with our literary and academic counterparts, but also to acquaint ourselves with contemporary Taiwanese society and culture. What we found along the way was a city and a government that works—a model we have much to learn from.

It was my second time in Kaohsiung and my sixth in Taiwan since my first visit in 2010, but those earlier sorties were either for tourism or for attending meetings and conferences, so we never really got to immerse ourselves in the place and its people. This time, Dr. Wu made sure that we went beyond casual handshakes and pleasantries with city and university officials to engage our hosts in in-depth conversations.

The first thing that usually strikes visitors about Taiwan is how modern it looks, especially when flying in through Taipei—the High Speed Rail (HSR), the wide roads, the skyscrapers (think Taipei 101, once the world’s tallest), the late-model cars. For quick comparisons, consider this: Taiwan’s population, at 24 million, is about a fifth of ours; in terms of land area, we are almost ten times larger; its nominal per capita GDP, however, is almost ten times larger than ours at US$35,000. Not surprisingly, Taiwan now ranks around 20th in the world in terms of its economic power.

That power came out of decades of dramatic transformation from an agricultural to a highly industrialized economy, starting with massive land reform and the adoption of policies that spurred export-driven growth. Industrialization itself went through key phases from the production of small, labor-intensive goods to heavy industry, electronics, software, and now AR/VR and AI tools and applications.

At a briefing at the Linhai Industrial Park by Dr. Paul Chung, a US-trained engineer who was one of the architects of this economic miracle, we learned how Taiwan built up the right environment for economic growth through such strategies as the creation of industrial parks (there are now 67 of them covering more than 32,000 hectares, with 13,000 companies employing 730,000 people and generating annual revenues of more than US$260 billion—almost eight times what all our OFWs contribute to the economy). The Taiwanese government has also implemented a one-stop-shop approach to investments, bringing together the approvals of many ministries and local governments under one roof.

Consistently, in modern times, the private sector has led the way forward, with the government acting as facilitator. This was much in evidence in Kaohsiung, Taiwan’s southern industrial hub that was, until relatively recently, a virtual cesspool, the prime exemplar of industrialization gone amuck. A strategic seaport, Kaohsiung grew out of the need to export Taiwanese sugar during the Japanese occupation (1895-1945); the sugar industry gave rise to railways that went far up north to Keelung and became the backbone of the country’s transport system. After the war, the Kuomintang who displaced the Japanese did little to improve things until a visionary mayor undertook reforms that cleaned up the place. Industry also achieved important synergies by adopting policies toward carbon neutrality and reducing waste—for example, one company’s blast furnace slag is being used to pave roads, and harmful carbon monoxide emissions have been rerouted as inputs to chemical companies.

Kaohsiung today is a city of 2.8 million people, a showcase of how runaway industrialization and urban blight can be reversed through good governance and political will. “People need responsible, responsive, and accountable government,” says Dr. Wu, a public-administration expert who worked for 15 years with five Kaohsiung mayors and who now serves as a visiting professor at UP’s National College of Public Administration and Governance (NCPAG).

A longtime visitor to the Philippines, Dr. Wu has made it his personal mission to promote Philippine-Taiwanese people-to-people relations—a concept he calls “taiwanihan”—in the conviction that the two countries have much to learn from each other and form a natural geographical, economic, and cultural partnership. “We are each other’s closest neighbor,” Wu says. “Taipei is 96 minutes away by train from Kaohsiung, but Kaohsiung is only 90 minutes away by air from the Philippines.”

Wu and his colleagues at NCPAG have been exploring the possibilities of developing a corridor of cooperation between Southern Taiwan and Northern Philippines, given their proximity. “We have the technology, you have the resources like biomass,” he adds, pointing out as well that taiwanihan doesn’t just mean a one-way relationship, but that the Philippines can also assist Taiwan with its growing needs, such as engineering talent and manpower. Some 8,000 Filipinos now work in Taiwanese factories, but Taiwan’s demand for highly skilled workers will only get higher as it moves into the next phase of its development, which will be heavily dependent on AI.

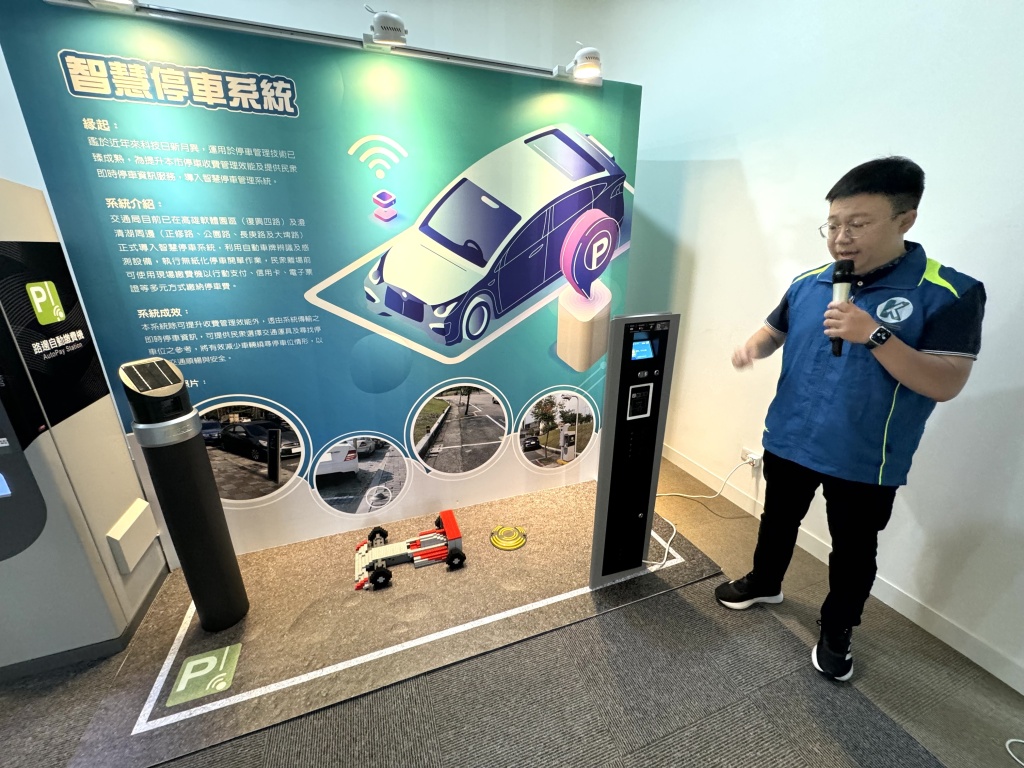

Artificial intelligence already takes care of many of Kaohsiung’s more mundane needs such as remote traffic monitoring and even the paid parking of vehicles, which has been outsourced by the government to a private entity. “We buy services, not things,” explains Dr. Wu. “The government provides the land for the parking, the private sector supplies the technology and the hardware. This is our version of public-private partnership: the government listens to the private sector, which can use the city as its lab.”

E-governance and decentralization led us to an unusual sight: we visited City Hall on a weekday and saw very few people in the lobby, unlike its Philippine counterparts. That doesn’t mean that government is distant from the citizens, as a “1999” complaints center receives and fields calls online or in person, employing the disabled to man its booths.

And even as AI has taken the forefront, it was abundantly clear that human intelligence and human priorities remained important. Good community governance, for one thing, was key to clean and peaceful neighborhoods (their village officials are appointed rather than elected, eliminating vote-buying). Their libraries alone show how and why the Taiwanese are succeeding: they not only have hundreds of thousands of books available to their citizens, but they have innovations such as the “Adopt-a-Book” program by which you borrow a book just based on a previous reader’s recommendation, and books in both Braille and regular text, so that sighted readers can read along with the blind and enjoy a story together. A city that goes that far to meet its people’s needs can’t fail.

Penman for Monday, December 10, 2018

Penman for Monday, December 10, 2018