Penman for Sunday, July 7, 2024

THE AUTHOR calls his book a “fantasy memoir,” and if it’s a genre you’re not familiar with, you wouldn’t be alone. Or maybe that’s just because you’re a dour and straight septuagenarian like me who doesn’t go out too much, watches true-crime shows to relax, and presses his pants and shines his shoes because, well, that’s the way it should be. I later googled the term, just to see what’s out there, and much to my surprise, it does exist—a genre defined by “imagination, escapism, and dreams,” with the stipulation that these fantasies, or products of the mind, are just as valid as memory in recreating one’s life.

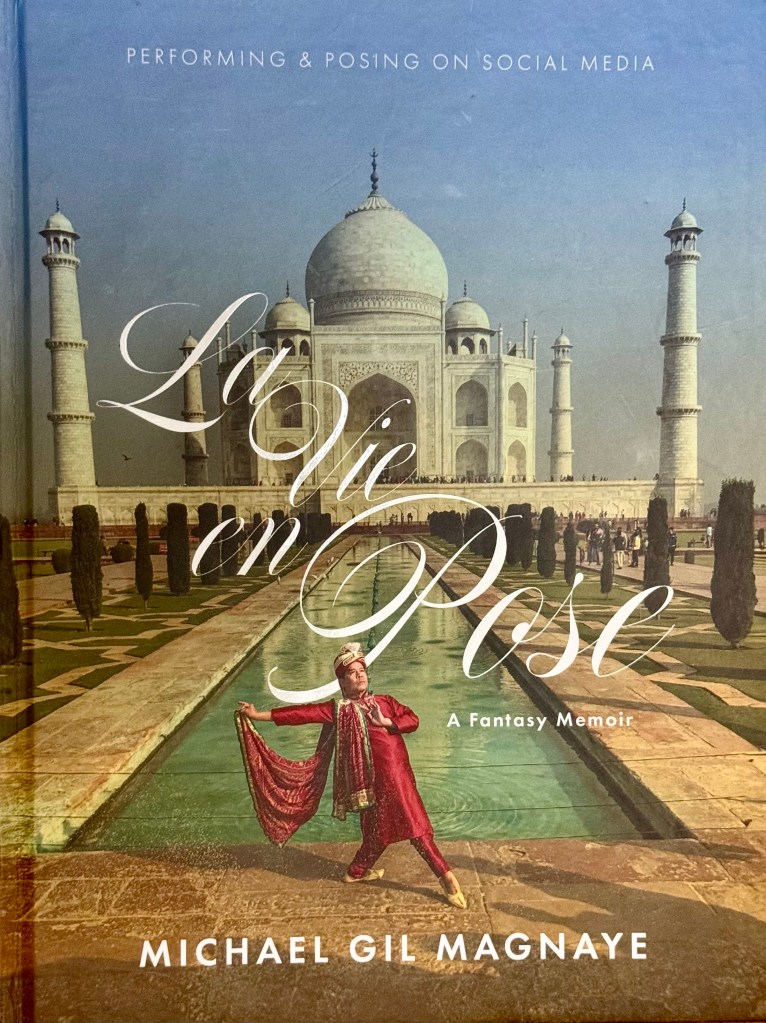

Thankfully, from the cover onward, Michael Gil Magnaye’s La Vie en Pose makes it purpose clear to the most casual and non-literary of readers: to have fun—while raising some very serious questions on the side about who and what we are (or pretend to be), what poses we ourselves assume, consciously or not, in our everyday lives, and how our identities are constructed by something so simple as what we wear.

La Vie en Pose is one of those rare books one can truly call “inspired,” resulting from the kind of half-crazy “What if?” lightbulb moment that strikes you over your tenth bottle of beer at 3 in the morning. Unlike many such flashes, this one stayed with Gil, took firmer shape, and turned into a virtual obsession—a first book to be completed by his 60th birthday, not just any book, not one of dry prose between the covers, but one certain to make a personal statement for the ages.

Magnaye, who works as an advisor to an international NGO, describes the book as “a fantasy memoir told in a hundred photographs of the author in costume, striking a pose around the world. Designed and photographed over a decade, these vignettes depict media celebrities, politicians, literary characters and wholly fictitious figures drawn from Magnaye’s fertile imagination. The collection offers satirical, often hilarious commentary on noteworthy personalities in pop culture, politics and history, from Game of Thrones to Bridgerton, from Jackie Onassis to Ruth Bader Ginsburg.”

Divided into eight chapters and edited by the celebrated Fil-Am writer Marivi Soliven, the book takes Gil around the world (none of this is AI—the photography took many years and plane flights to complete), posing in various locales and contexts, often in costume, to mimic or to pay homage to familiar figures and situations. The pop-culture setups will likely elicit the most laughs and smiles—Tina Turner, Maria von Trapp, and of course Barbie all get their comeuppance—and the UP Oblation poses (thankfully just backsides) show the malayong lupain that our iskolars ng bayan have reached (Gil studied and taught Humanities in UP before going to Stanford for his master’s). The levity aside, he strikes thoughtful, almost architectural, poses against spare backdrops. He draws his husband Roy, a normally reticent software engineer, into take-offs on couples (Ari and Jackie, Ennis and Jack). The effect is both riotous and reflective, a visual essay on how pop and political culture have overwhelmed us, but also how we have appropriated and domesticated them for our own purposes, if only to say, “Hey, I can be as good that!”

The poet and queer theorist J. Neil Garcia explains it better in this note he posted online about the 30thanniversary of the landmark Ladlad anthology he co-edited with Danton Remoto: “Queer creativity is itself an integral component of the equality message, and not simply a means to an end. Since the freedom of the imagination is perhaps where all freedom begins, it is clear that giving the queer artist the power or the ability to create their own texts and art works needs to be seen as a vital objective of the equality movement, one of whose primary interests must be in securing this imaginative and/or cognitive ability above all. Hence, we need to insist on the truth that queer creativity isn’t simply a tool to promote the equality message and other activist agendas; rather, queer creativity itself is part of the agenda—is part of the equality message itself (and so, queer creativity is not just a means to an end; quite crucially, as the best evidence and enactment we have of individual and collective agency, even against the harshest of odds, it is an end, in itself).”

For Gil—whom I was friends with back when he still had a girlfriend and confronting his sexuality—the book is more than a personal celebration (he launched it in UP last June 23 to mark his 60th birthday); it’s also an assertion of his rights as a queer (the preferred term these days to “gay”) person—and by extension, of all other LGBTQ+ people as well—to express themselves creatively. In his introduction, he notes that “This book is born at a fraught moment in gender politics. Some states in the US have passed legislation that attacks transgender youth for their chosen wardrobe or preferred pronouns. A drag artist in the Philippines has been jailed for performing an irreverent dance interpretation of a Catholic hymn. Such adverse events would seem to suggest that cross-dressing is an act of subversion. I would argue that cross-dressing and mimicry are strategies that drag queens, drag kings, non-binary performers, and gender benders employ to resist, challenge, navigate, and extricate themselves from systems imposed by traditional constructs. And it’s a lot of fun.”

La Vie en Pose most surely is. Copies might still be available at the UP Center for Women’s and Gender Studies.