Qwertyman for Monday, August 14, 2023

TWO SPEECHES delivered by graduating students of the University of the Philippines made the rounds of social media last week, garnering generally positive responses for their forthrightness. One was more strident than the other, but both carried essentially the same message: we need to reframe the way we look at the education of the poor, and what true success should mean for the working student.

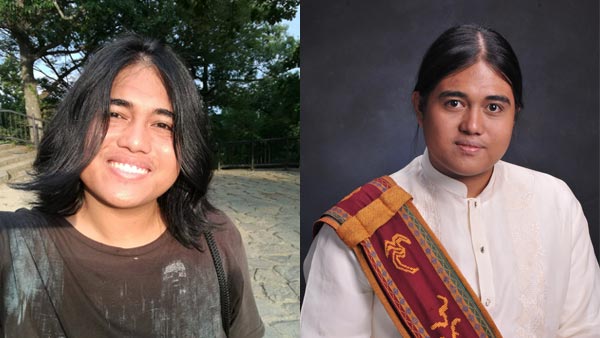

The first was Val Anghelito R. Llamelo, summa cum laude and class valedictorian, Bachelor of Public Administration. The son of an OFW, Val began working at a very young age at a BPO, as a marketing assistant, and as a tutor to support his needs and that of his family’s. He was, almost needless to say, the first UP graduate his family produced, and finishing summa against all odds was the icing on the cake.

He wasn’t there, he said, to deliver the usual valedictory speech you’d expect from a person with his kind of success story. He was grateful for his opportunities, but he didn’t feel like celebrating his hard-won triumph, which people would typically applaud for its sheer improbability. And that, precisely, was the problem, according to Val.

“Why should I be an exception?” he asked in so many words. “Why can’t more Filipinos from my background do well in college and finish like I did? Why does access to a quality education remain the privilege of a few? During the pandemic, how many poor students underperformed because of their lack of access to digital technology?”

Again I’m paraphrasing here, but Val went on to say, “I don’t want to be your inspiration or role model. No one should have to endure what I faced. I want you to be disgruntled enough with the system to demand something better and not settle for less, to yearn for a system where working students, indigenous people, and individuals from impoverished families can have fair opportunities to study and to succeed. Praising us gives politicians in power an excuse to renege on their commitment to improve our lives. We overvalue resilience. Using the familiar analogy of the glass that’s half-full and half-empty, we’re often made to feel that we should be contented with the fact that it’s half-full, but we should focus on the fact that it’s half-empty, and should hold our leaders accountable for filling it up.”

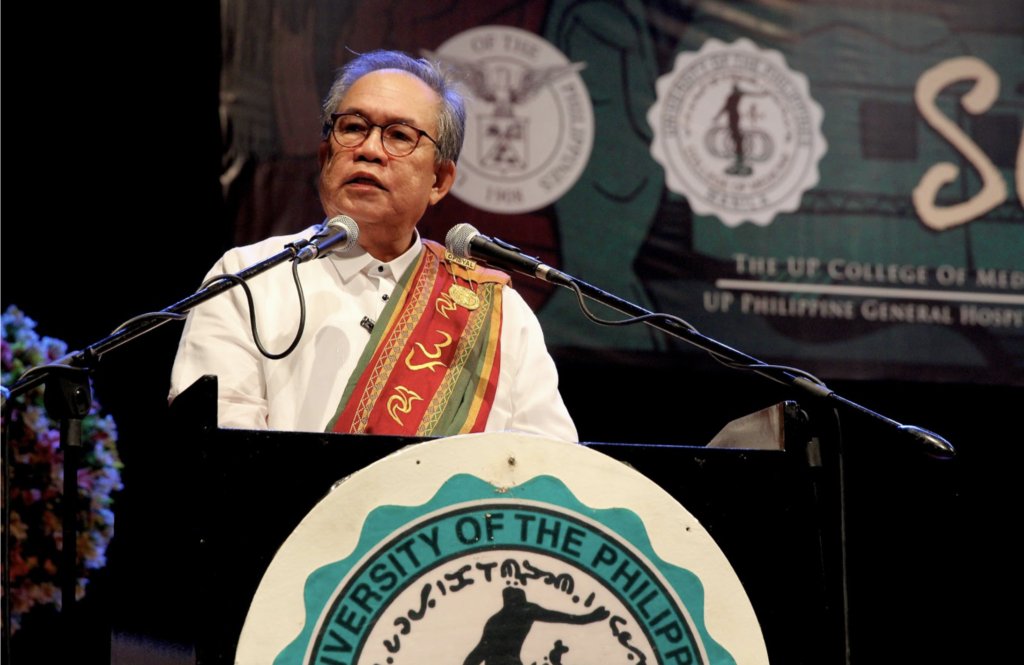

The other speaker was Leo Jaminola, a BS Political Science cum laude and MA Demography graduate who juggled six jobs—as an encoder, transcriptionist, library student assistant, tutor, writer, and food vendor—to complete his bachelor’s degree.

“Graduating with honors back then was nothing short of a miracle,” says Leo. “In the years that followed, the list of jobs I took just grew longer as I became a research assistant, a government employee, a development worker, and a consultant for different projects with some engagements overlapping with each other.

“The past years have been a long-winding maze of seeking financial security and I have still yet to find a way out of this crisis. From full-time work, part-time work, and competitions, I did my best to provide not only for myself but also for my family.

“While some of my peers have hefty investments in high-yield financial instruments, here I am still overthinking whether I deserve an upgrade to a large Coke while ordering at the local fast food chain.

“During my childhood, I saw how poverty manifested itself in the form of cramped makeshift houses, children playing near litter-filled canals, and senior citizens succumbing to illnesses without even getting a proper diagnosis. Growing up, I thought of these as normal occurrences that should be accepted as it is the way of life. Now, I do not think that this should be the norm.

“Some people will say that poverty is a personal failure and that the members of my community should work harder but I know better. One of the things that I learned from my experience is that hard work as the primary factor in being successful is a myth. That’s not to say that it doesn’t play a role but privilege and access to resources have greater impacts on whether a person ends up successful or not.

“If hard work is all it took, then the many young breadwinners I know who continue to support their families while chasing their own dreams would not be constantly organizing their budget trackers to find ways how to stretch their salary until the next payday.

“Others will read this and use it as some kind of living proof that people, even those from the most marginalized groups, can make it in life simply by working hard rather than addressing structural barriers. But what of those who didn’t make it despite working as hard or even harder than me? How are their experiences not evidence of the continued inaccessibility of education and opportunities in our country?

“Rather than success, we should see my experience and the stories of so many others as systemic failures. If anything, my story should make us angry and move us to demand a much better society—one that allows our people to live with dignity, dream freely, and enjoy equal opportunities.”

The speeches echo each other, but then so have the “model” valedictories that Val and Leo so forcefully seek to subvert. Indeed, the usual narrative we hear is that of the poor boy (or girl) made good, followed by congratulatory praises for his or her tenacity and faith in Divine Providence. (Some of them, like the poor boy from Lubao, even become President.)

I have to admit that we find such stories inspiring if not necessary, because they offer the possibility of salvation for a lucky and plucky few. But we have to bear in mind as well—as Val and Leo emphasize—that for every summit achieved like theirs lie hundreds if not thousands of others who never got past base camp, not for lack of talent or will but simply for lack of means. To succeed as a nation and society depends much less on producing exceptional one-offs than on leveling the playing field for most.

(Photos from Philstarlife and pep.ph)