Penman for Monday, April 15, 2013

Penman for Monday, April 15, 2013

AMONG THE most interesting topics that came up in the recent UP National Writers Workshop in Baguio was that of writing the memoir. More and more people—and not necessarily celebrities or historical figures—have been writing their memoirs lately, and it could even be argued that many blog entries are, effectively, memoirs, although the quality of the prose and of the sensibility behind it might vary widely. No matter, for now: what’s important is that we’ve put a considerable value on what people say they remember, so it’s as good a time as any to look at memoir-writing with a critical eye, as we did in Baguio.

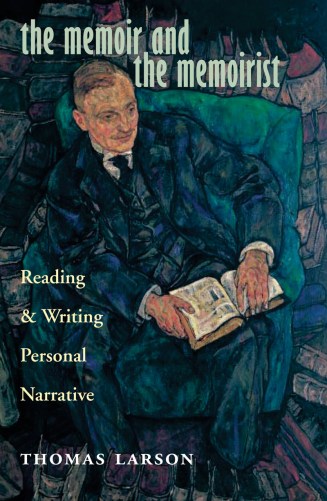

Having been assigned to lead that discussion, I drew on a book that I’ve had my students in creative nonfiction read before they mine their own lives for material with which to complete the course. Written by Thomas Larson, the book is titled The Memoir and the Memoirist: Reading and Writing Personal Narrative, and it was published in 2007 in the US by the Swallow Press of the University of Ohio. It was my wife Beng who found the book for me during one of our visits to San Diego, and I’m very happy that she did. I rarely read books from cover to cover in a few sittings, but this was one of those exceptions. I found myself nodding and putting check marks on the margins here and there, so cogently did Larson raise his points.

So rather than dilute Larson’s wisdom with too much of my own commentary, and since this isn’t a full-scale lecture on the memoir, I’m going to quote extensively from his book by way of raising issues that the potential memoirists among my readers can consider.

Let me just take off from what I said last week about the writing of historical fiction—about how the past speaks to the present, and how, beyond nostalgia, history is of value to the writer as material with which to explore why we are who and what we are today. Memoir writing, when you come right down to it, poses the same challenges and opportunities as historical fiction, except that it really happened, and it happened to you.

But in the memoir, Larson suggests, the past in a vital sense did not just happen; it continues to happen. In other words, the past is never over, and it is the memoirist’s job to be aware of and to remark on the happening.

Quote: “You need to emphasize that which captivates you in the present…. The past drama is not the only drama. The present drama of recollection is equally alive, equally in and of the story. [The memoirist finds] that as she remembers she is being emotionally altered by what she remembers.”

Memoir is different from autobiography, Larson says, in that it deals with small, intimate, ambiguous portions of a life rather than a coherent whole. The memoirist’s stance is one of self-doubt rather than the biographer’s certitude.

Quote: “The Encyclopedia Britannica describes the old plural form, ‘memoirs’, as that which emphasizes ‘what is remembered rather than who is remembering.’ If we invert this, we can call a book that emphasizes the who over the what—the shown over the summed, the found over the known, the recent over the historical, the emotional over the reasoned—a memoir…. It cannot be the record of the past as autobiography tries to be. Memoir is a record, a chamber-sized scoring of one part of the past.”

Larson says that indeed, the true subject of memoir is not the past but the mutable self.

Quote: “[In] the construction of a relative self in the memoir… the person who is writing the memoir now is inseparable from the person the writer who is remembering them. The goal is to disclose what the writer is discovering about these persons…. What the memoirist does is connect the past self to—and within—the present writer as the means of getting at the truth of his identity.”

In revisiting the past, Larson refers to what Virginia Woolf calls “moments of being,” those events, instances, and decisions that define the self. The memoirist actively seeks out these moments, and explores and amplifies them until they acquire a kind of resonance.

Quote: “The exceptional moments are ‘moments of being.’ They are physically overwhelming and, over time, represent a legendary quality about the self.”

Context is vital to the definition of this self.

Quote: “The memoir’s prime stylistic distinction is a give-and-take between narration and analysis, one that directs the memoirist to both show and tell…. In memoir, how we have lived with ourselves teeter-totters with how we have lived with others—not only people, but cultures, ideas, politics, religions, history and more.”

The memoir is therefore more than raw memory, but is rather memory mediated and processed by a host of factors, including one’s position and interests in the present.

There will, of course, be times when the memoirist seems unsure of exactly what happened—and that uncertainty is part of the game. The best memoirists, Larson says, don’t deliberately invent events (as in that infamous case of James Frey); they don’t have to.

Quote: “In the memoir, the truth and the figuring out the truth abide. The best way to deal with the tension between fact and memory, as one uncovers the tension in the course of one’s writing, is to admit to the tension—not to cover it up…. What we learn in memoir writing is that memory has far more of its own agency than we thought, that the very act of remembering may alter what did occur…. This layered simultaneity… is the prime relational dynamic between the memoir and the memoirist: the remembering self and the remembered self.”

And finally, there’s no escape from chronology, says Larson. The whole point of memoir is that one thing will lead to another, and that what we’re trying to palpate from these flows of memory is the underlying plot of our lives—even if, or perhaps because, we don’t know what will happen next. The memoir is itself a story, but is also part of a longer story yet to be fully grasped and told.

Quote: “Be it abuse, death, grief, a fall off a horse or the rise to the presidency, a memoir is, as tale and discovery, always consequential, even if one tries narratively to evade or delay the consequence…. Memoir is reminding us that its largely essayistic direction allows readers and writers not to know ahead of time what will be said. And to preserve that not-knowing, that tentativeness, is vital to the memoir’s story.”

Penman for Monday, April 8, 2013

Penman for Monday, April 8, 2013