Qwertyman for Monday, August 28, 2023

HAVE A problem? No worries—the Philippine government will make a rule to fix it (maybe). Don’t have a problem? No matter—the Philippine government will make a rule to give you one.

Some days it feels like all that government exists for is to make new rules, because, well, it’s the government, and so it has to look and sound like one. Never mind what the preamble to our Constitution states, imploring the aid of Almighty God to “establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity, the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace.” Forget the rule of law and all that jazz; all hail the rule of rules.

Two pronouncements by our hallowed poohbahs caught our attention in recent weeks.

The first was an order from the Vice President and Secretary of Education, DepEd Order No. 21, directing in its implementing guidelines that all public schools must ensure that “school grounds, classrooms and all their walls and other school facilities are clean and free from unnecessary artwork, decorations, tarpaulins, and posters at all times…. Classroom walls shall remain bare and devoid of posters, decorations, or other posted materials. Classrooms should not be used to stockpile materials and should be clear of other unused items or items for disposal.”

Why? Because these were distractions to learning, explained the good secretary, presumably including in her edict the pictures of past presidents, national heroes, posters of Philippine birds and plants, TV-movie idols, Mama Mary, cellphone and softdrink advertisements, half-naked women, CPP-NPA recruitment posters, the periodic table of elements, weapons of Moroland, and the winking Jesus.

I actually found myself agreeing with the removal of some of these popular items of wall décor, especially the pictures of politicians, which doubtlessly produce anxiety and despair in those who might contemplate them seriously. The good presidents will make you ask, “Where did all that goodness go?” The bad ones will invite only dismay and even self-loathing: “How did these jokers even make it to Malacañang? So you can still be that kind of person and become President? What on earth were we thinking?” This leads to even more profound and troublesome questions about the nature and practice of democracy, which a poorly trained and underpaid sixth-grade teacher will be hard put to answer, undermining whatever little authority she still exerts over her students. (To her credit, Sec. Sara reportedly removed her own picture from a classroom she visited.)

But Rizal, Bonifacio, Mabini, Tandang Sora, and the usual pantheon of Philippine heroes decking our classroom walls? Will removing their visages encourage students to think more deeply about their Science or Math problems, or will young minds simply drift off to Roblox, Taylor Swift, and Spongebob Squarepants? Will making our classrooms look as bare as prisons (and even prisons have calendars and pinups) lead to a spike in student attentiveness and performance? What does it say of DepEd—with all the academic resources and intelligence funds at its disposal—that directives like this are issued apparently on a whim and without prior and proper study? Where was the attention to science and education that the secretary was aiming for?

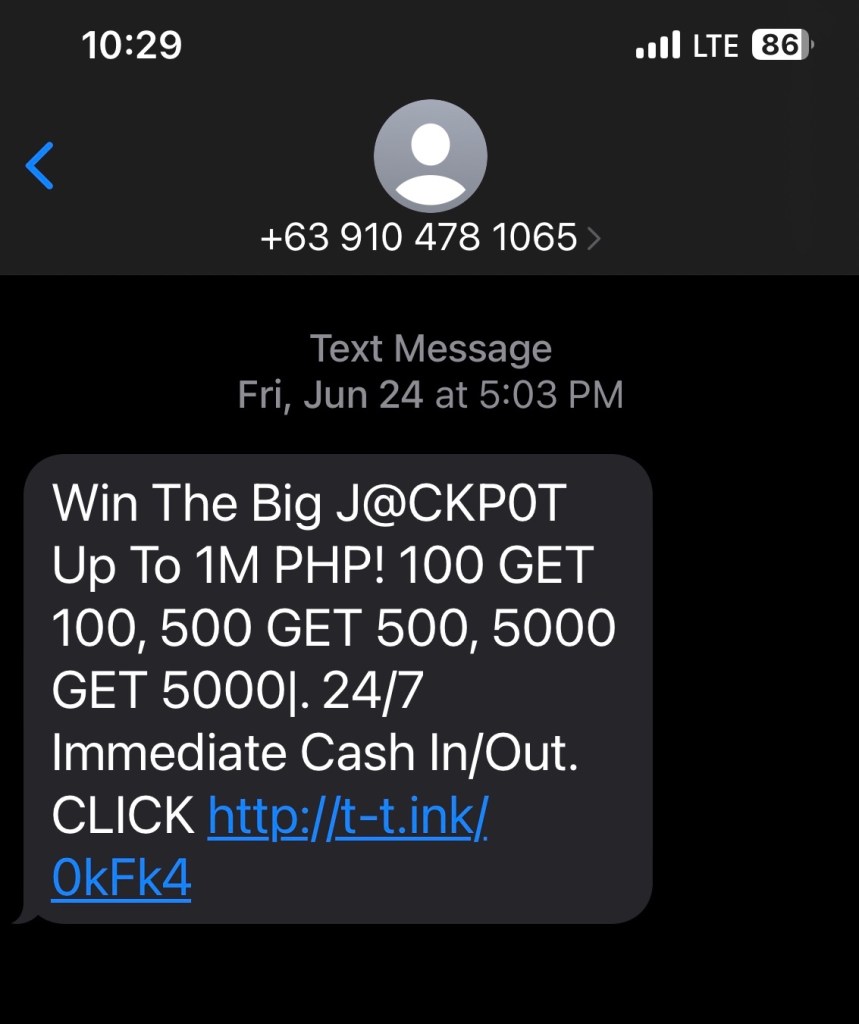

The other new rule that sent us screaming to our group chats was the imposition of new guidelines for foreign travel by the Inter-Agency Council Against Trafficking, announced by the Department of Justice, supposedly to curb the incidence of human trafficking, which we all acknowledge t0 be a serious problem. But is this a serious solution?

Under the new guidelines, Pinoys going abroad to see the sakura in Tokyo or to watch the New Year’s Eve ball drop in Manhattan won’t get past NAIA immigration without showing their flight and hotel bookings, proof of their financial capacity to afford their trip, and proof of employment. That’s a lot of paperwork to bring along, and if you’ve seen how long the queues can get at NAIA even without these papers in the way, you can imagine what they’re going to be like with each single document having to be scrutinized by an immigration officer. There’s an even longer list of additional requirements for people traveling under sponsorship and for OFWs—including a requirement for a child traveling with his or her parents to present a PSA-issued birth certificate, which was already a requirement for that child to have been issued a passport.

Exactly what this rigmarole adds to the reduction of trafficking is unclear to my muddled mind, because it seems to me that any good trafficker worth his or her illegal fees will be smart enough to produce the fake documents their wards will need to slip through airport security. As experience has shown, it isn’t even fake documentation but corruption and connivance that have greased the wheels of trafficking.

Which reminds me, I received a letter some time ago from an expat Briton and a longtime Philippine resident named Thomas O’Donnell, complaining about such unnecessary requirements as the filing of annual reports by foreigners in this country. The Philippines has a reciprocity agreement with other countries such as the UK, Thomas says, but the UK doesn’t require Philippine residents there to do the same thing. So was it—like many of our other rules—just something to keep our bureaucrats occupied (or possibly, profitably occupied)? Where was the fun in the Philippines, Thomas lamented, and how was a fellow like him supposed to love it?

Having lived here for 23 years, Thomas clearly has found other, countervailing reasons for staying on, but he has a point. Despite an anti-red tape law in the books, we still invent ways to complicate the simplest things. And answer me this: if the DepEd chief thinks that bare walls can lead to clearer thinking, shouldn’t we declutter our travel processes as well, so we can all sit in the departure lounge in peace with an hour to spare, waiting for our flight (that will likely be delayed, but that’s another story)?