Qwertyman for Monday, March 18, 2024

IT WAS in 1986, shortly after EDSA and my arrival in the US for my graduate studies, that I began thinking about what would eventually become my master’s thesis and my first novel, Killing Time in a Warm Place. It was published by Anvil in 1992 when I came home to resume teaching after completing my PhD.

For those who’ve never heard of it, the novel is a semi-autobiographical account of coming of age during the Marcos years, from the point of view of a Filipino who makes the traditional journey from island to metropolis to the world at large, becoming, in the process, a kind of political chameleon.

I had sent the first draft directly to several US publishers—my first try at getting a book published abroad—and one of them, Alfred Knopf, responded. They were interested, they said, but they needed some revisions. I knew very little about the book publishing industry then; I had no agent, wasn’t sure what lay ahead, and was in a hurry to see my book out, so I passed on Knopf—which turned out to be a titan in literary publishing—and went with Anvil, which had barely just opened.

I haven’t regretted that decision, although the Knopf deal, had it pushed through, would have been a tremendous break, not just for myself but for Philippine literature as a whole. I could understand that after EDSA, US publishing was hungry for books from and about the Philippines, so that opportunity was there, but I was also impatient to be read as a novelist by my fellow Filipinos, after having written short stories and plays.

Anvil published the book in many printings and editions over the next two decades, as it got on the syllabi of college teachers who were looking for a novel in English on martial law, alongside Lualhati Bautista’s iconic Dekada 70. This has been my greatest reward and satisfaction from this book—knowing that somehow, it helped some of my countrymen understand what they went through.

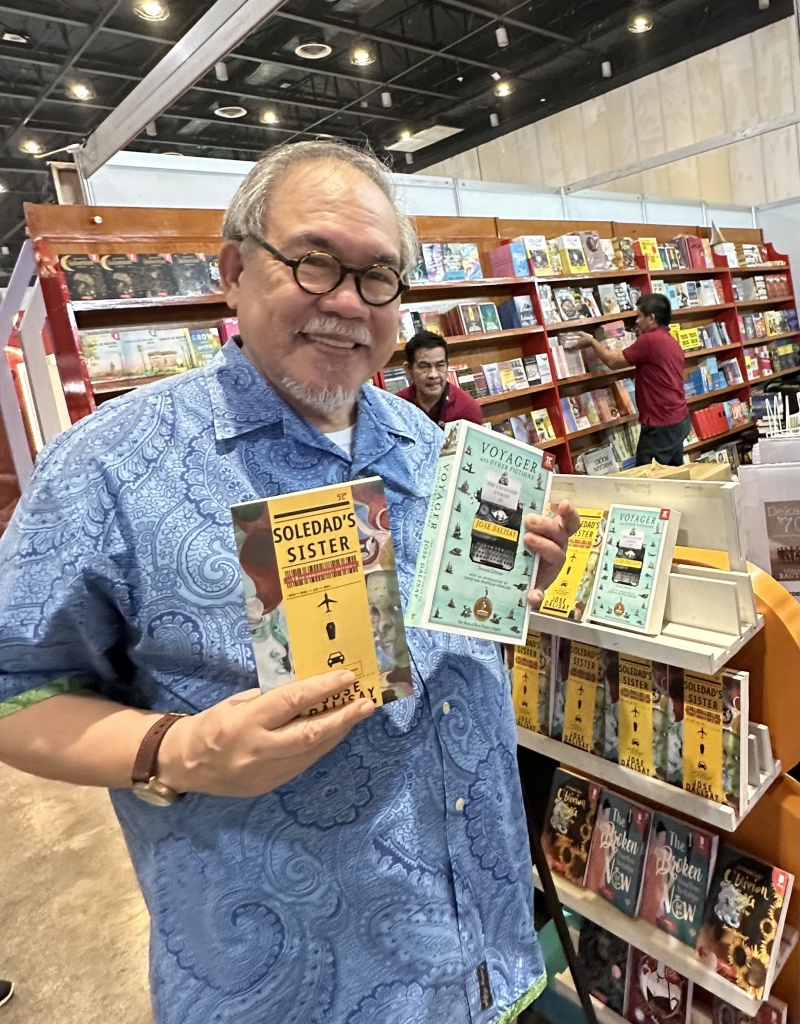

It took a while for the novel to gain some traction overseas. In 2010, it was published in the US by Schaffner Press in a dual edition with my second novel, Soledad’s Sister. In 2012, it was translated into Spanish by Maria Alcaraz and published in Barcelona by Libros del Asteroide under the title Pasando el rato en un pais calido.

A few months ago, I received the happy news from my publisher Anvil that Killing Time was being picked up by the German publisher of Soledad’s Sister, which had apparently been doing well in the German market. So now the book is being translated into German, hopefully for a launch by Transit Verlag in time for the Frankfurt Book Fair this October, leading up to our big Frankfurt Guest of Honor year in 2025.

But I didn’t write this column just to tell you about the story of a book—rather, I wanted to say something about the story of its story.

In a message to Anvil a few days ago, my German publisher requested that I write a short epilogue to the novel, given that it’s been more than 30 years since it first came out, and that many things have happened since to the world and the Philippines—the Internet, Trump, and fake news, among others.

So I sat down and wrote the short piece below, which I’m sharing with you since it’s highly unlikely that you’ll come across, or understand, the German translation of this epilogue if and when the new edition comes out. Here goes:

I began writing this novel in 1986, shortly after the downfall of the Marcos regime. That happened because of a massive uprising in Manila’s streets that made headlines and became a kind of model for peaceful anti-authoritarian movements worldwide. I proudly took part in that revolt, and felt the euphoria of liberation after more than a decade of martial law. It was a moment I would often return to and savor as the Iron Curtain fell and as various and largely non-violent revolutions took place elsewhere, including the Arab Spring.

I thought then that the best thing I could do was to write a novel that would try and explain how and why people fell under the spell of a dictatorship, as they did under Nazi Germany—not sparing myself, having been complicit in its later actions as an employee of the regime. I wrote it—in English—in America, mainly to fulfill my graduate school requirements, but also to celebrate our hard-won victory and share the good news with the world.

Almost four decades later, the seemingly unthinkable has happened: the right is back in power, not only in the Philippines but in many places we had thought to be reformed democracies. The optimism sweeping the planet toward the end of the 20th century has given way to a darkening horizon, a hardening of hearts, a closing of minds. Our most basic freedoms and values are under stiff and unrelenting assault, from forces we now realize had never really been vanquished but had merely been lying in wait, biding their time, seeking an opportunity for revival amidst the excesses of late capitalism.

And once again I am hearing the siren song of despotism, and see the eyes of people glazing over in the desperate desire for quick relief from their troubles, for quick salvation. I hear the march of boots, to which many young citizens—their ears plugged by loud music—seem indifferent. Even among many of their elders is a renascent yearning for the simple discipline of strongman rule.

I see all these and I wonder if I should write a sequel, an update for the new century, but what would be the point of repetition? My novel was supposed to be about the past. Why is it so suddenly pertinent again?