Penman for Monday, June 2, 2014

Penman for Monday, June 2, 2014

IT WAS with great sadness that I read last week about the passing, at age 92, of Alfredo M. Velayo—an outstanding accountant, teacher, citizen, and philanthropist. Fred Velayo was best known as the “V” in SGV or Sycip Gorres Velayo & Co., the pioneering accounting firm that he co-founded with Washington SyCip and Ramon Gorres after the Second World War.

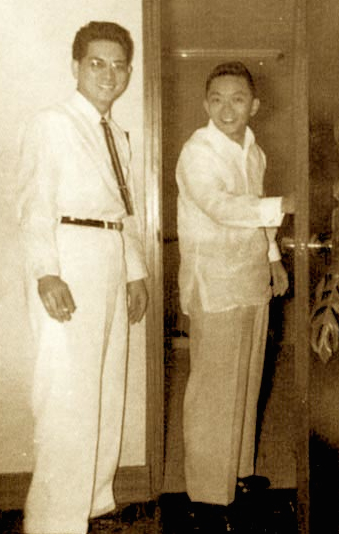

I had the great privilege and opportunity of writing Wash SyCip’s biography some years ago, and among the delights of that assignment was meeting and interviewing Fred Velayo—who, like Wash, was already well advanced in years but still sprightly and brimming with boyish mischief. Tall, handsome, genial, and an irrepressible joker, Fred was the perfect foil for the more private and more formal Wash.

Fred and Wash had one of the most memorable friendships (today they call these unusually durable male bondings “bromances”) I’ve ever come across—certainly one of the longest ones, starting in the 1920s at the tender age of five, when both boys attended Padre Burgos Elementary School in Sampaloc, Manila. Their first meeting, on the first day of school, wasn’t too auspicious. The children started crying when their mothers and yayas had to leave—except Wash’s mother, who was a good friend of the principal’s, and was allowed to stay. So Wash sat there unperturbed, and Fred would remember with a chuckle that “Right that first day, of course, we all hated him. Naturally. He was looking at us, saying ‘Why the hell are you little kids crying?’”

With his brilliant mind and work ethic—qualities that Fred himself displayed—Wash would never again have to lean back on privilege to get ahead. But a little luck never hurt. Bright as they were, both boys got accelerated in grade school—not once, but twice. In Wash’s case, it didn’t occur just twice, but thrice. Fred always wondered how that happened when he was just as smart as Wash—and Wash didn’t tell him the real reason until they were in their mid-70s in 1996, when Wash let slip that there had been room in the upper class for just one more boy, and the teacher chose him—alphabetically.

Fred and Wash caught up with each other in V. Mapa High; they both lived in Sta. Mesa and walked to school together. The friendship—and the rivalry—continued over high school, then went on to college at the University of Sto. Tomas, from which both graduated summa cum laude. As I would note in my book, “To no one’s great surprise, Wash finished his four-year course in two-and-a-half years, graduating a full year ahead of Fred, and ending up being Fred’s teacher in one subject at the ripe old age of 17. Amazingly, Fred would close the gap a bit by also getting to teach in his junior year, also at 17.”

Wash went to Columbia in New York for his PhD and was caught by the War there, and joined the US Army as a codebreaker in India; Fred stayed behind and married the girl who would become his wife of over seven decades, Harriet. After the War, their paths crossed again—Wash came home, and Fred went to the States with Harriet and joined the Army.

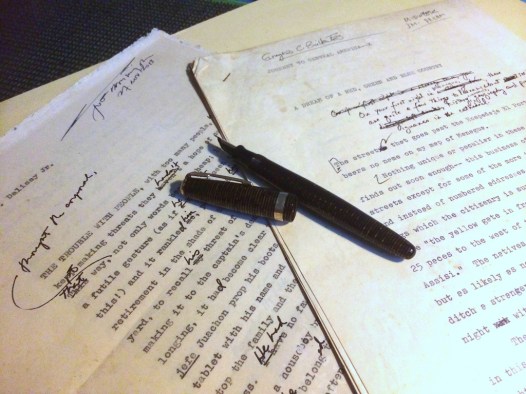

But when Wash had to go back to the US to fulfill a residency requirement (he had to take US citizenship to be able to work as a codebreaker), he needed someone to mind the small accounting business he had started in Manila, and there was no other person who could fit that bill but his old pal Fred Velayo. He wrote Fred a letter that would become part of SGV lore. He told Fred, on December 16, 1946: “Dear Fred, Received your letter from Alaska the day after I mailed my last letter—but hasten to write you this note. You should try to return as soon as possible as the top opportunities here are excellent—the earlier you start the better. Master’s degree doesn’t mean much—ninety percent of the FEU accounting faculty do not have anything more than a bachelor’s degree—including some of the highest paid ones. But now is the time to get started as I believe that the more you put it off, the greater will be the competition when you get settled. There’s a lot of accounting work—and you can combine this with teaching and importing (with Miller-Gates)—the returns are much larger here than in the States and the competition for a capable person is much less. So cabron, get the hell on that boat and come out here. The various bills before Congress will undoubtedly increase the work of CPAs—but you have to get in on the ground floor… some come over fast. You can also try your hand at insurance—good and profitable line. Cost of living has been going down during the past month in spite of strikes in the States. Housing isn’t worse than in the States—so make up your mind—be your own boss—and come to virgin territory! See you soon. Wash.”

At first, Fred said no—he and Harriet had just begun to settle down in the US—but in January 1947, Fred changed his mind and took a plane home. The rest, as they say, is accounting history. Fred had a funny story about what supposedly happened next:

“One day, years later, Wash came back. He was still earning a little more than me. And so he came to my room. (WS) Fred, this has got to stop. (AMV) What are you talking about? (WS) The fact that I’m earning more from the firm than you. From now on everything will be equal. Our monthly drawings, even perks, club membership, everything, the same. It’s not fair to you that I’m getting a little more. (AMV) SOB, how come it took you so long? (WS) Never mind, from now on we’ll be equal partners. As he walked out of my room, he started laughing. (WS) Anyway, you’ll always be my junior partner. (AMV) After you said we’re equal from now on? (WS) I can’t help it. I’m 57 days older than you. He even counted!”

When we interviewed Fred for Wash’s book (Fred already had his own biography published before Wash), he told us a hoary joke, often recounted at SGV reunions, about dying ahead of Wash and getting to heaven sooner. I guess he knew something Wash didn’t. Bon voyage, Fred Velayo.

Penman for Monday, May 12, 2014

Penman for Monday, May 12, 2014

Penman for Monday, May 5, 2014

Penman for Monday, May 5, 2014