Qwertyman for Monday, March 11, 2024

YOU’LL FORGIVE me this “proud papa” moment if I preface this week’s column with the news that our unica hija Demi Dalisay Ricario, who’s unbelievably turning 50 later this year, represented Asian-Americans—and indeed the Philippines—on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC recently to lobby for changes in US health laws on behalf of patients. That’s an ocean and a continent away and doesn’t really affect us, but what’s salient here is that Demi went there on behalf of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) as an advocate for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) concerns—and that touches on our lives as Filipinos.

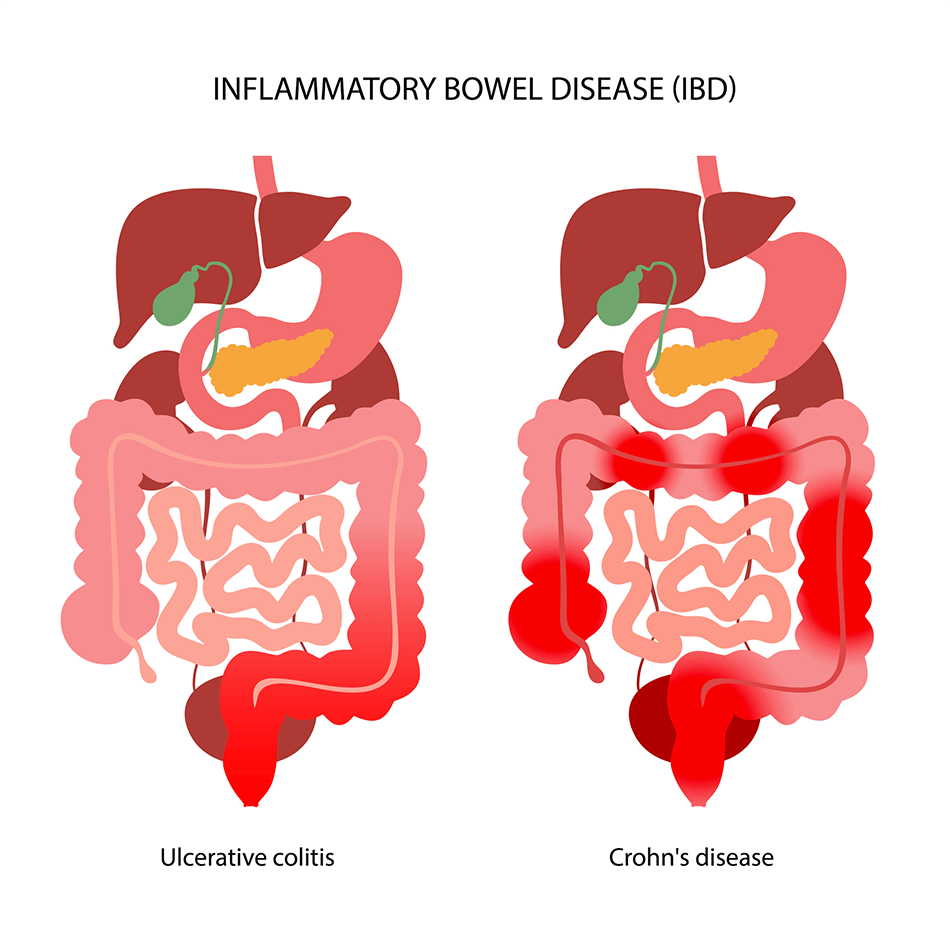

IBD is one of those little-known and often misunderstood diseases that can turn life into a living hell for its sufferers. It comes in two variants—ulcerative colitis (UC) and the more severe Crohn’s disease (CD), both of them involving inflammation of parts or all of the intestines. Often accompanied by bloody diarrhea, UC and CD and can be extremely painful and be lifelong burdens—or even turn fatal.

Their causes remain unknown, but genetics, environmental factors, and immune responses seem to be active factors. Remedies include strict dietary changes and employing colostomy bags. Patients can find their social lives diminished or even be stigmatized. It’s not that common—according to the IBD Club of the Philippines, UC hits 1.22 out of 100,000 Filipinos and CD just 0.35, but it’s that same obscurity that makes it difficult to recognize, diagnose, and treat properly. In our culture where people tend to ignore or diminish their ailments—especially embarrassing ones—and consult doctors only as a last resort, the problem gets magnified.

It was on one of our visits with Demi in San Diego ten years ago that she fell terribly ill with blood in her stool, and despite all the tools available to modern American medicine, no one could tell why. Only months later was she positively diagnosed with UC, bringing both relief and radical lifestyle changes, especially to her diet (she can’t eat anything with wheat like ordinary sliced bread, among others). She held a high-pressure job as a frontliner in one of San Diego’s premium hotels, and stress is a high inflammatory factor.

“People often struggle to understand that IBD is an invisible illness, which means that sufferers might look healthy outwardly yet still experience significant health challenges,” Demi says. “This misconception is particularly challenging for individuals like me, who worked in high-end environments like the US Grant hotel, where maintaining an elegant appearance and managing demanding clients was part of the job. The contrast between looking ‘well’ and feeling unwell led to misunderstandings, as people would say, ‘But you don’t look sick!’

“The unpredictability of IBD symptoms significantly impacts mental health and daily life (it makes me anxious sometimes). Fluctuating symptoms such as frequent restroom visits and pain can hinder social interactions and activities. The inconsistency of the disease makes it difficult to commit to plans, as fatigue is a common issue. Additionally, managing a career can be problematic; frequent medical appointments and unexpected flare-ups often disrupt regular work schedules. This was my experience at The Grant, where I had to forego managerial opportunities to avoid exacerbating my condition. Additionally, managing relationships and friendships can be complex with IBD.”

IBD patients have a hard time at parties and social events, especially in the Philippines, where pakikisama is part of a strong food culture. People with colitis can’t eat ordinary bread or drink milk (think halo-halo). Demi has had to be adept at declining offers of food—a no-no for Pinoys—and explaining her unusual condition.

“Before heading to any event or restaurant, I take a look at the menu online to figure out what I can eat. I’ve even gotten into the habit of giving the host a heads-up about my diet to make sure there’s something on the table I can actually enjoy. When it’s time for those long flights to places like Manila, I pack a stash of gut-friendly snacks in my carry-on (usually gluten-free bread, granola bars, nuts, and fruit). Whenever available, I pre-order gluten-free meals for my flights. After dealing with IBD for almost a decade, I’ve learned the hard way what foods are my friends and which ones are foes, such as gluten and lactose.”

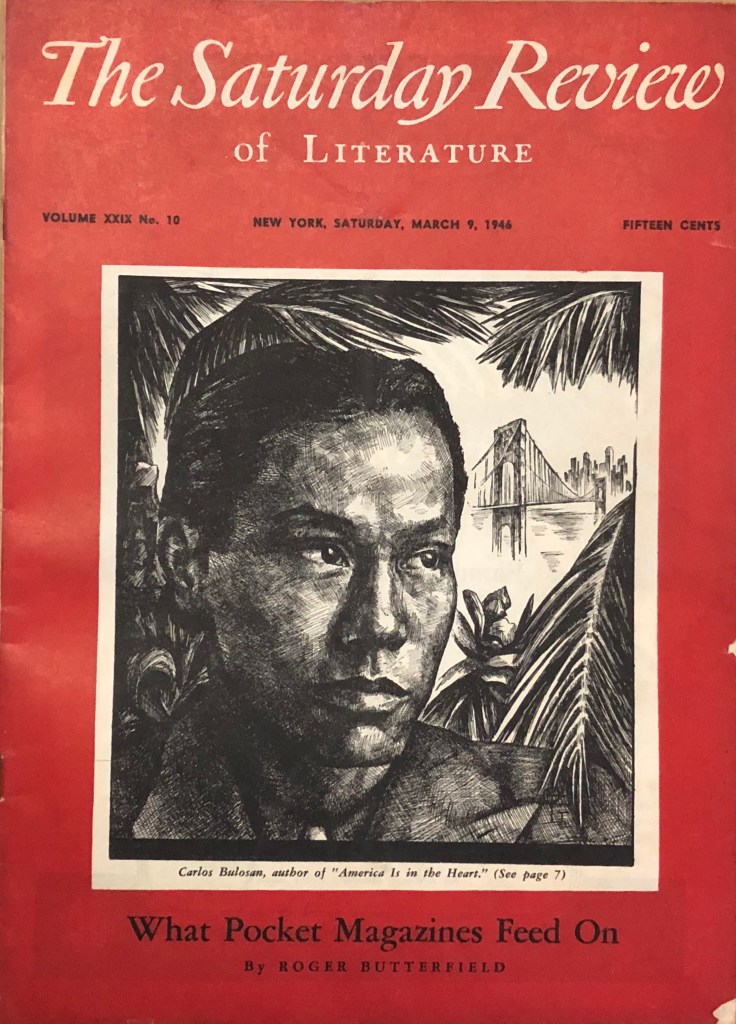

To help her fellow Pinoys deal with IBD, Demi created a “Dear Colitis” Facebook page, also to encourage them to come out in the open and realize that they have a virtual global support group. Her advocacy continues online and with various entities like Pfizer, the Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, and the Crohn’s Colitis Philippines FB group. Last year she was invited by the American Gastroenterological Association to join six other advocates as part of their pilot Patient Influencer Program to help promote IBD awareness, giving her the opportunity to participate in this year’s Digestive Disease National Coalition Public Policy Forum in DC.

She explains that “Filipinos dealing with IBD should be well-informed about their condition and discerning about the reliability of information sources they encounter. It’s crucial for patients to be their own advocates, boldly voicing their needs and concerns whether at home, in the workplace, or in social gatherings. This self-advocacy is key to maintaining a good quality of life. Cultural concepts such as hiya (shame or embarrassment), pakikisama (camaraderie or fitting in), and the fear of being a pabigat (burden) can pose significant challenges. These factors might discourage individuals from speaking out about their condition, but overcoming these barriers is essential for their well-being and mental health. By confidently communicating their needs and educating those around them, Filipino IBD patients can navigate their condition more effectively while fostering understanding and support in their respective circles.”

Spoken like, well, a spokesperson, but I think a good one for the job.

(Illustration from Johns Hopkins Medicine)