Qwertyman for Monday, July 7, 2025

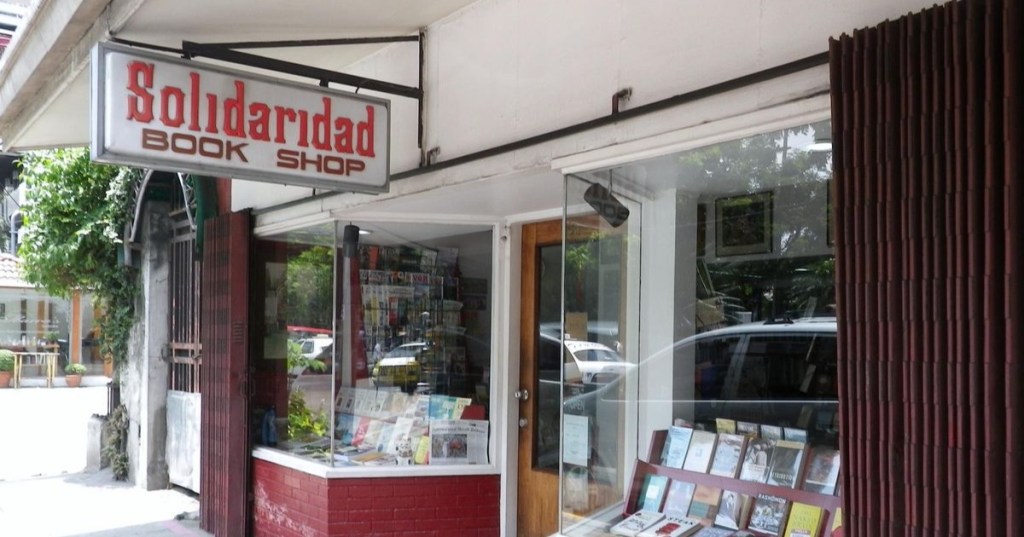

THE RECENT announcement of the impending sale of the Solidaridad bookshop in Ermita owned and run by the family of the late National Artist F. Sionil Jose understandably triggered a wave of nostalgia for the place, the old man, his dear wife Tessie, and for a bygone era when people strolled into book stores over their lunch break or after work to browse and pick up an Updike, a Le Guin, or a Garcia Marquez—and, of course, a Sionil Jose, and get it signed by the man himself if he was luckily around. Five decades ago, as a writer for the National Economic and Development Authority just a couple of blocks away on the same street, that browser would have been me, for whom Solidaridad and the equally legendary Erehwon nearby were a godsend, an unlisted perk.

Indeed Solidaridad and FSJ (or Manong Frankie, as we his juniors called him) were inseparably conjoined in the public’s imagination of a man who was not only our most productive and best-known novelist but also an indefatigable purveyor of great literature and critical if occasionally controversial thinking, through his journal Solidarity and his long-running column “Hindsight,” this very space I was honored to have inherited.

Like many others—even those with whom he had quarreled fiercely—I was deeply saddened when Manong Frankie passed away three years ago. It was particularly bittersweet for me because we had become quite close in his last years, after having been somewhat estranged for the longest time.

He had taken me under his wing on a writers’ conference in Bali in 1983, in a group of young, aspiring writers finding their way in a broadening literary world. But shortly after, in an interview with National Public Radio in America where I had gone to study, I offered my rather injudicious opinion of his prose—not mine alone—which he must have gotten wind of and found disparaging, because he gave me the cold shoulder afterwards. Like other younger writers, I would bristle at his hectoring moods—which I would better understand as I myself got older—during which he lamented the seeming alienation of the Filipino writer from his or her own social and political reality.

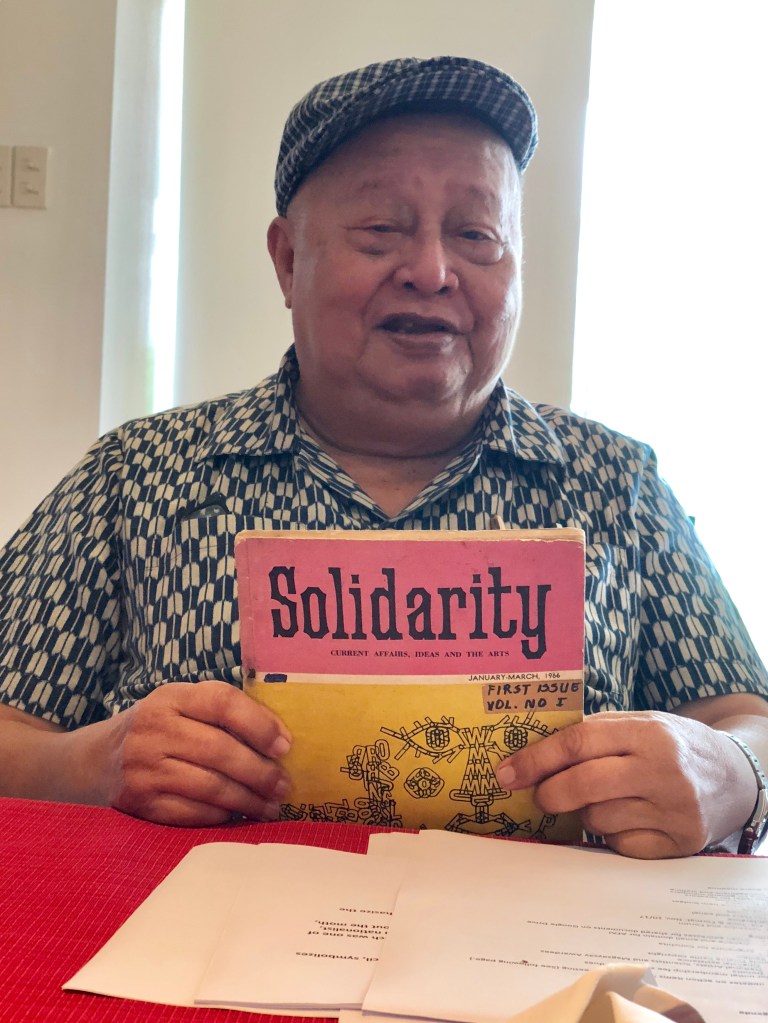

It was a concern we happened to share, and he began to know and appreciate me as someone who eschewed academic snobbery as much as he did, having transitioned to fiction from a background in journalism rather than the writers’ workshop system that he was deeply dubious of. In other words, we had more in common than each of us thought, and our work in the Akademyang Filipino brought us closer together. At one time I gifted him with the very first issue of Solidarity—Vol. I, No. 1—which I had found, and which he had not seen for ages; he was happy. After my speech at the Palancas in 2017, he came up to shake my hand.

Ironically, this happened at a time when FSJ, ever strongly opinionated, turned off many of his readers with his pro-Duterte sentiments, his putdowns of Nobel prizewinner Maria Ressa and others he thought undeserving of their fame, and his acerbic loathing of certain families he considered oligarchs despite their long having been supplanted by new and far more ravenous overlords. I did not share these views, and he knew that, but I think we had quietly decided that our friendship was more important than our politics. Shortly before he died, he sent me a brief letter that will be a cherished secret to keep until I myself pass on.

I didn’t learn writing from Manong Frankie; rather, I observed and admired his persistence and perseverance, literally writing to the last on what turned out to be his deathbed. I enjoyed his stories more than his novels, but in the end my own preferences don’t matter. He left a sprawling, robust, and indelible body of work that for many readers here and overseas will define Philippine literature in English for the latter 20th century. He led what our mutual friend the novelist Charlson Ong called “a well-managed life,” building a legacy partly through Solidaridad, Solidarity, and Philippine PEN which he led for a long time, apart of course from his work, and making sure he was heard when he spoke.

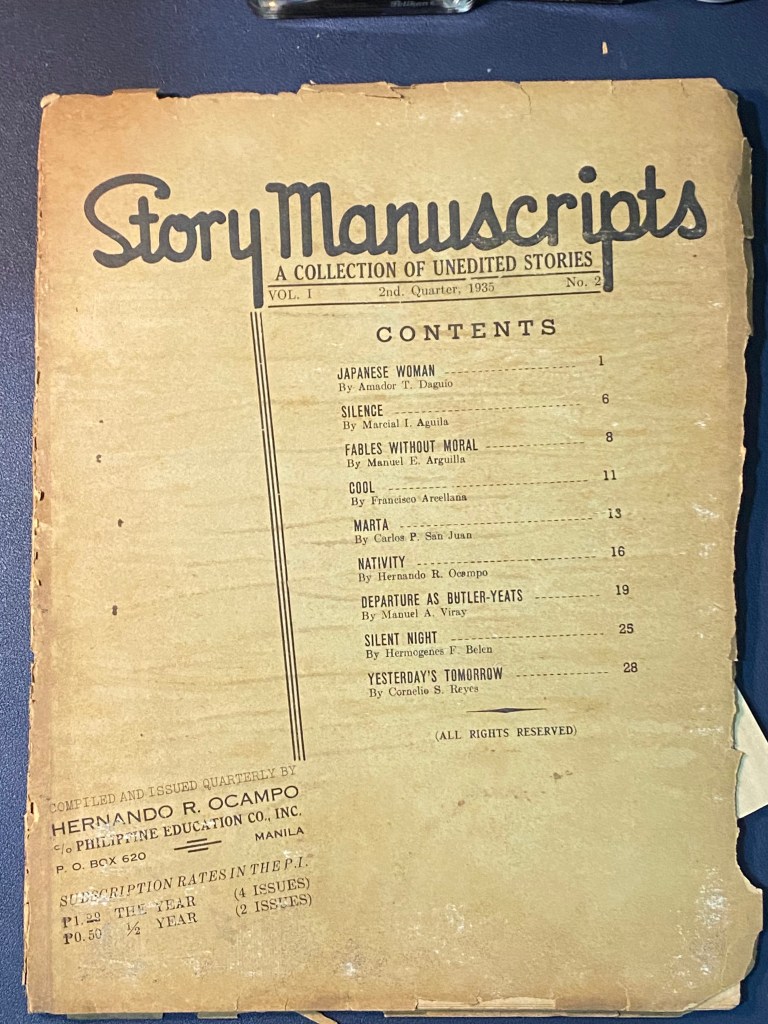

His passing reminded me of the other members of his generation—his seniors and juniors by a decade or so—whom my generation in turn looked up to and at the same time, in that perpetual cycle of revolt and renewal, sought to depose. Nick Joaquin we adored as much for his prose as for his prodigious drinking (and seriously, for putting as much of his heart and craft into his journalism as into his fiction). NVM Gonzalez, who happened to have been born in Romblon (and not in Mindoro as many think) several kilometers away and forty years ahead of me, had that common touch many citified writers lost. Edilberto Tiempo I owe for urging me to return to school and devote my life to studying and writing rather than to bureaucratic servitude.

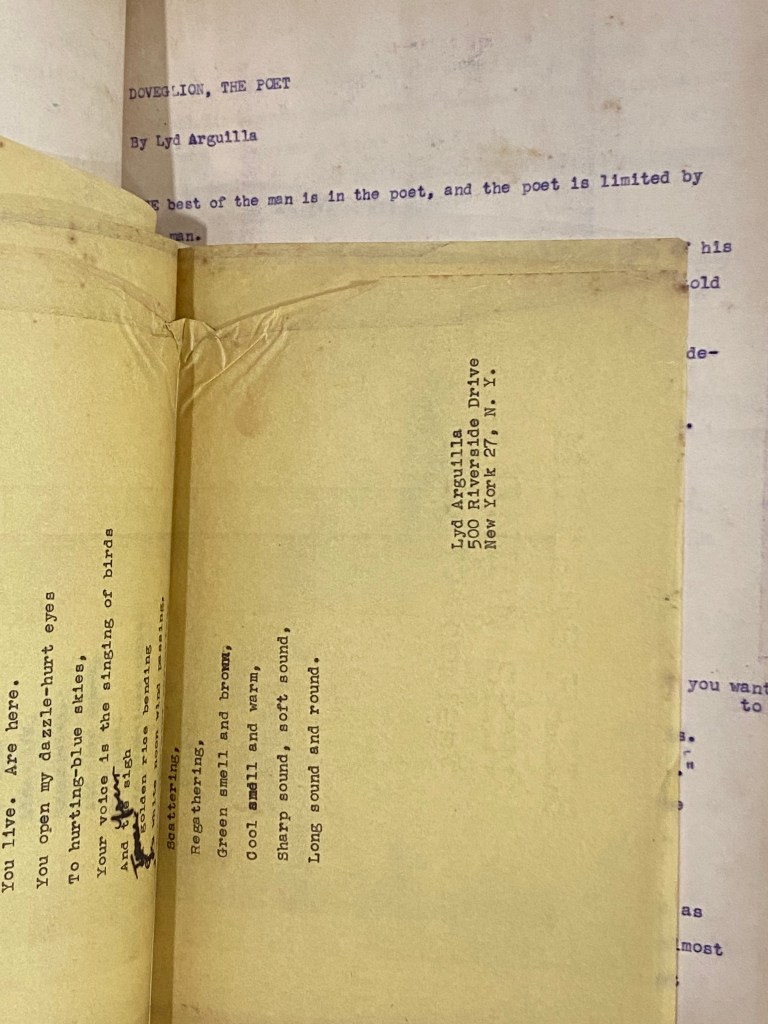

Bienvenido Santos, twinkly-eyed and gently smiling, was my favorite of them all in terms of the quietude but also the emotional resonance of his stories, so graceful and yet so powerful. If I were to think of a literary father, it would have been Franz Arcellana, whose work may have been so vastly different from mine and yet, as my mentor in school, was the one I sought to please, slipping my story drafts under his office door and praying for his approval. Gregorio Brillantes, the youngest of them and perhaps more properly belonging to the next generation along with Gemino Abad, has been my writing hero for his superlative technique and unfailing sense of character. All these men (and women as well, for whom a separate story should be told) have taught me and my peers much, not just about the craft of writing but just as importantly the writing life, this vocation of books and words we have ddevote ourselves to for the bliss and yet also often the anguish of finding meaning in life through language.

Manong Frankie has passed on and soon so will his fabled bookshop, but his words, as well as ours, now have a life of their own.