Penman for Friday, May 9, 2025

MY MOM Emy turns 97 today, May 9. Some years, her birthday coincides with Mothers’ Day, saving us a celebration. But that’s a bit deceptive, because when you have a parent this old living with you, every day is a blessing worth celebrating.

It’s hard to believe that Mommy Emy is a lot healthier than she was a quarter-century ago, when we all feared that we were about to lose her, just a few years after our dad Joe Sr. passed away in 1996 from a ruptured aneurysm. After all, the stories usually went that way—one spouse dies, the other follows soon after, out of grief or a sense of life suddenly losing its purpose and meaning. Whatever caused it, Mom fell ill with tuberculosis, with the disease progressing so devastatingly that she was coughing blood and feeling terribly weak. Luckily, her doctor put her on a menu of cutting-edge pills that, over two years, miraculously banished the TB, well enough for her to secure a US visa to join my sister Elaine in California.

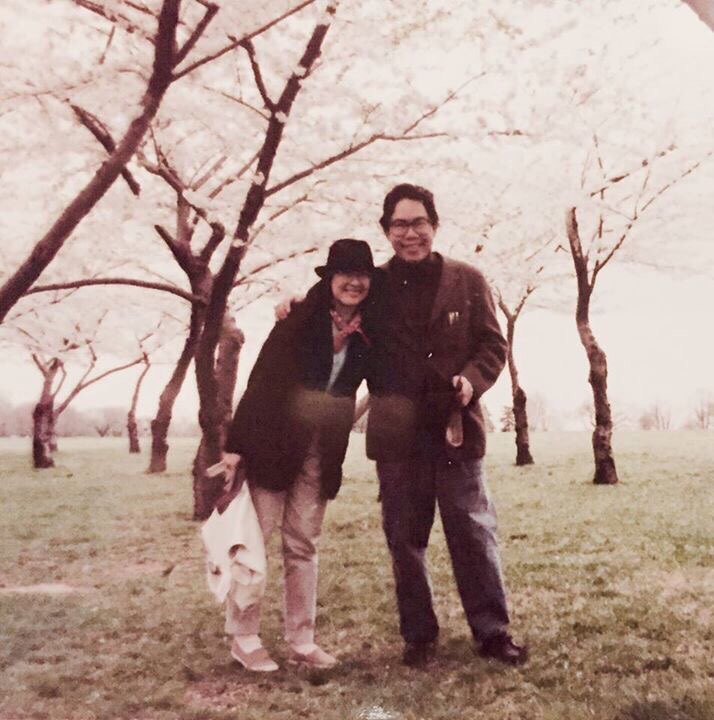

Over the next decade, she regained her strength, and even as she sorely missed our dad, indulged in a newfound zest for life—traveling with my sisters in the US, Canada, and Europe, visiting glaciers, going up the Tower of Pisa, and settling into in the quiet suburbs of Virginia just outside of DC with Elaine and her husband Eddie. She stayed there long enough to gain a green card, and we would visit her every now and then, sensing that, despite Elaine’s and Eddie’s loving care, she was pining for home. Eventually she did return to Manila, giving up her green card. “I want to die here,” she stated with finality, and that was that.

One thing I love about my mom is her eminently practical sense. Since at least five years ago, she has written out clear instructions about what to do in case she was dying—no intubation, no extraordinary efforts to prolong her life, just as quiet and as painless a departure as could be managed. Last year we went out with her to the department store to pick out her funeral dress—a macabre chore to some, but for us, and especially for her, a cheerful excursion, with much discussion about this cut or that shade of blue (yes, she’s going in blue).

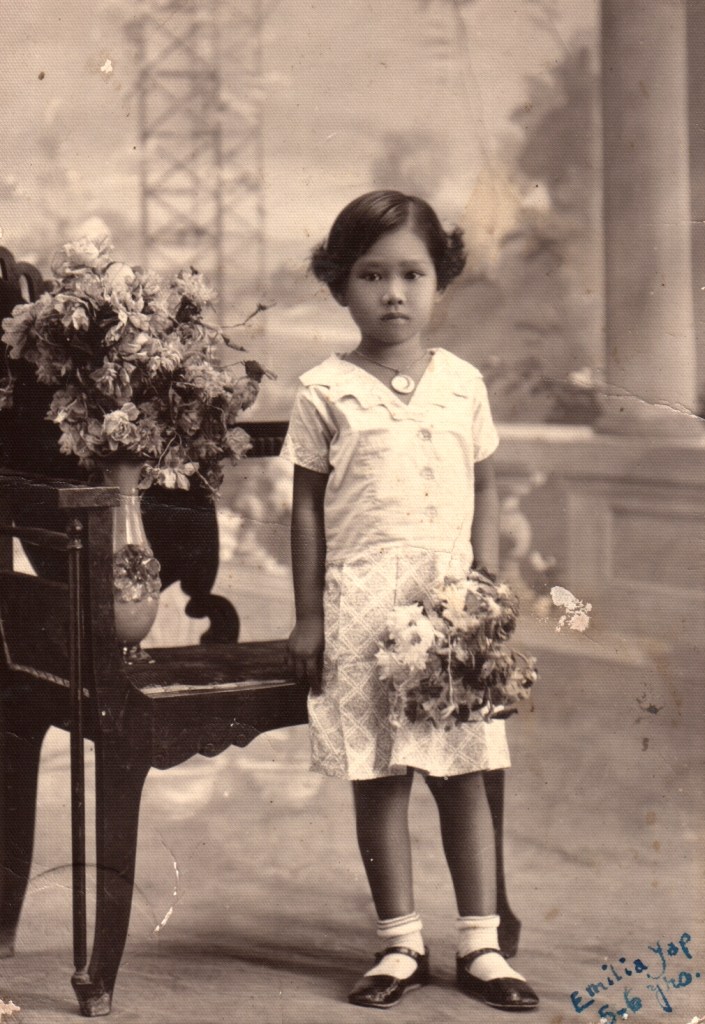

She was born in Romblon a landlord’s youngest daughter, the apple of his eye, the only one to go to UP in Manila, from where she graduated with an Education degree. Growing up, she rode a horse on the farm and accompanied my Lolo Cosme on his trips to Manila. She remembers how easy and provident life was back then: “We would go to the beach and Papa would throw a net into the water, not far from shore, and it would come up teeming with fish, and the fish were everywhere, jumping in the air.”

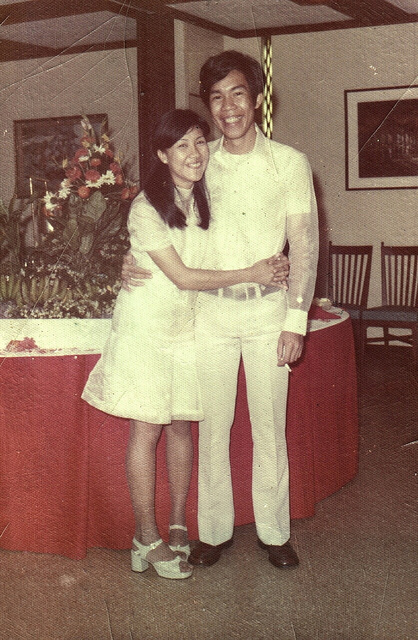

My father was a sharecropper’s grandson, too poor to finish college but with a sharp mind and a gift for words that must have swept Emy off her feet. Like many couples of their time and place, they decided to seek their fortune in Manila a few years after I was born. Their love was deep but often tested, given that there were five of us to raise. There was even a time when Dad was a barker for jeepneys, and Mom worked as postal clerk for minimum wage. Life sometimes felt like a soap opera, but we all pulled through, and often it was Emy’s internal toughness that made sure we were fed and ready for school.

Since her return from Virginia, my mom has been staying with us in UP Diliman, occasionally spending time with my three other siblings (Elaine is now in Canada). Still figure-conscious despite her age, she watches what she eats, but we indulge her every whim. It doesn’t take much to make her happy—almost daily Facetime calls from Elaine in Canada and our daughter Demi in the US, a weekly manicure, visits from her brood, and Tuesday Circle get-togethers with her group of neighborhood friends, among whom she is now most senior.

What surprises people who meet her for the first time is how strong and alert she is. She uses a cane and a walker (but only because we insist), but she takes long walks daily around the yard and just outside the house. Her steps are getting slower and harder, but she marched for Leni in 2022, in gratitude for which the VP sent her a video greeting on her 95th birthday. She reads without glasses, and plays word games on her iPad with a passion; she follows Netflix, and watches the news with tart commentary. She’s as prayerful and religious as they come, but is staunchly liberal in her politics. “All my friends are dead” is her frequent complaint, quickly balanced by “But I’m so thankful for my children!” She and Beng share long meals and laughter-filled conversations. We have no doubt that as long as she takes her maintenance meds and doesn’t suffer a bad fall, she’ll live to be a happy hundred.

Emilia Yap Dalisay’s name will never make it to the society pages, but she’s the biggest star in our small stretch of sky, and taking care of her has been our grandest privilege. Happy birthday, Mommy Emy, and may you have as many more years to come as God’s kindness will allow.