Penman for Monday, November 10, 2014

Penman for Monday, November 10, 2014

BENG AND I were in Philadelphia and New York these past two weekends, so I could do more interviews for my martial-law book project and also get in touch with a few old friends. I normally keep a very low profile and don’t tell or call people when I travel to places where friends are living, not because I’m a snob, but because I don’t want to be a bother, knowing what it’s like when somebody drops in from the blue and throws your schedule out of whack.

But there are always some friends you never mind breaking your routine for, and who never seem to mind, either, if you break theirs. And I was glad to meet up in Manhattan with two such writer-friends, the poet and essayist Luis “Luigi” Francia and the fictionist Gina Apostol, both of whom live and work in New York. Luigi teaches at Hunter College and Gina at the Fieldston School.

The first time I met Luigi, many years ago in a Malate bar on one of his visits home from New York where he has been living since 1970, I remember seeing his calling card, which described him thus beneath the name: “POET. EDITOR. PRINCE.” It seemed cheeky and chic, and I was deeply impressed, being none of the above. (I’ve since written some middling poetry and have done my share of editing chores, but remain utterly unprincely.)

I had the recent pleasure of writing a blurb for Luigi’s forthcoming collection of essays titled RE: Reviews, Recollections, Reflections, to be published by the University of the Philippines Press, and this is what I said:

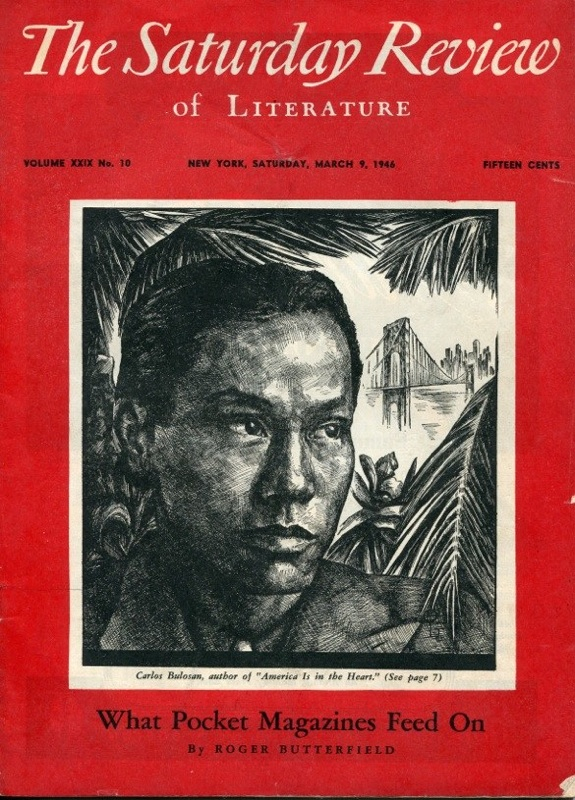

“Luis Francia knows New York and America better than many of the native-born, but he never loses his moorings, his critical awareness of what it means to be Filipino-American. But these essays are about far more than racial politics, as they chronicle the travails of that most blessed and in other ways most cursed of citizens—the artist, particularly the artist abroad, for whom alienation acts as a lens that magnifies and reshapes every little thing that crosses the eye. The most arresting and delightful reads are his portraits of the expatriate masters who preceded him in America—most notably Jose Garcia Villa, lover of martinis and hater of cheese. Despite the plaints, Francia has been clearly and distinctly privileged to be where he has been and to see what he has seen, and he shares that privilege with us in this well-wrought collection.”

Gina was my batchmate when I returned to finish my undergrad studies in UP in the early ‘80s; I was ten years older than everyone else, so I was kuya to all of them. It was a time when we were all dreaming of finding a way to take our graduate studies abroad—as English and writing majors, we wanted to become the next Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the next Sylvia Plath, the next Ian McEwan, the next Pablo Neruda, and so on; as Pinoys, we wanted to see America. Eventually, we just became our older selves, but we did get to see the States through one ticket-paying subterfuge or other—for me, a Fulbright grant; for Fidelito Cortes, a Wallace Stegner fellowship; for Ramon Bautista, an assistantship at Wichita. But we had to compete for these, while all the brilliant Gina had to do was to lick a few stamps and mail a couple of her typewritten stories off to John Barth, who directed the writing program at Johns Hopkins and who wrote her back forthwith to offer her an assistantship, smitten as he was with her talent. It was pure magic, in those pre-email days.

That brash young woman from Tacloban who flew off to Baltimore would go on to write several prizewinning novels. Gun Dealers’ Daughter, published by W. W. Norton, won the 2013 PEN Open Book Award given by the PEN American Center to outstanding works by authors of color to promote racial and ethnic diversity within the literary and publishing communities. (Luigi himself had won this prize in 2002, the first year it was given, for his nonfiction book The Eye of the Fish.)

Here’s what the judges said about that novel in their citation: “You will read Gun Dealers’ Daughter wondering where Gina Apostol novels have been all these years (in the Philippines, it turns out). You will feel sure (and you will be correct) that you have discovered a great fiction writer in the midst of making literary history. Gun Dealers’ Daughter is a story of young people who rebel against their parents, have sex with the wrong people, and betray those they should be most loyal to…. This is coming of age in the 1980s, Philippine dictatorship style, where college students are killed for their activism. The telling is fractured, as are the times…. Not only does this novel make an argument for social revolution, it makes an argument for the role of literature in revolution—the argument being that literature can be revolution.”

These then were the two literary luminaries who happened to be my friends (or should that be the other way around?) whom I was happy to set up a date with in a coffee shop in the West Village, near the High Line (an elevated garden and walkway that deserves its own story, among other New York landmarks). The coffee place was full, so we brought our steaming cups instead up to the roof deck of Gina’s apartment a few blocks away, pausing for a picture in front of the late Jose Garcia Villa’s old place on Greenwich Street. “This was where he held court,” said Luigi, one of Villa’s acolytes. “Nonoy Marcelo also lived in this area for many years, and I did, too, back when the rent was 65 dollars a month.” Then Gina added, “That white place is where John Lennon and Yoko Ono lived.” And I thought, if they’d stayed here instead of moving to the Dakota, he might still be alive.

We went up to the roof deck and Beng and I savored the scenery in all its 360-degree magnificence, as the sun set in the west and the full moon rose in the east, competing with the Empire State’s tricolor spire. We talked books, life, and loves over Frangelico, bread, and cheese; channeling Villa, I steered clear of the curd. Looking sharp and happy despite a recent illness, Gina said that her iPhone’s Siri had told her, in response to a question, “I’m just glad to be alive!” At that instant, we all were.