Qwertyman for Monday, June 23, 2025

(Photo of Los Cabos by Kurt Nichols)

I WAS looking for a topic for this column last week when it occurred to me that I had been staring it in the face, in the news and in the Facebook feed that, like for many, my days begin and end with. It was the omnipresence of death, in its many forms and guises, swift and slow, painless and agonizing, arriving on whispery feet and crashing through one’s roof or window.

“A screaming comes across the sky,” the line with which Thomas Pynchon famously begins his novel Gravity’s Rainbow, was how death and destruction came last week to hundreds in Kiev, Tehran, and Tel Aviv, in missiles and drones designed and manufactured for but one purpose: to deliver death by inexact algorithm to place-names plotted on digital maps.

In India we marveled at the horror and the mystery of one survivor escaping a catastrophic plane crash barely a minute after take-off: a moment when most of us would have just begun to fidget with the entertainment controls, wondering whether to take in a comedy or a thriller for the next two hours and what the meal choices will be.

In Minnesota, a MAGA gunman stalked Democratic lawmakers and their families, shooting four and killing two on a long list of intended targets—murders that a Republican senator reflexively attributed to “Marxists not getting what they want.”

Most appalling was the report of Israeli tanks firing into a crowd of Palestinians lining up for food in Gaza, an incident that led to about 60 deaths and more than 200 wounded, for which the Israelis apologized with this statement: “The IDF regrets any harm to uninvolved individuals and operates to minimize harm as much as possible to them while maintaining the safety of our troops.”

As if the news isn’t enough, every time we scroll through our social media accounts, more deaths emerge, in the now-familiar solitary-candle meme and in the garlanded portraits of the recently departed. Facebook has become our new obituary page, our book of condolences, our virtual wake. The friend or the kinsman in us takes the loss with the requisite pain and grief; the enemy with muttered thankfulness, or more rarely forgiveness; the human with relief, that we are reading and not being read about.

Death in the news is meant to outrage us, and it still does, at least for a while, especially senseless and preventable death, willful murder, and patent genocide. But sadly we can only take so much, even with the keenest of consciences; there is something in our brains, a control or shut-off valve, that says “Enough” and leads us back into the immediate and comprehensible present, back to chocolate cupcakes, Torx screwdrivers, tomorrow’s court hearing, and Lola’s birthday. This, we remind ourselves, is life, the only one we have, our chief responsibility above all others to live and to give meaning to.

We try to make sense of death as much as we do of life, and for those of us of a certain age, that means the acceptance of its inevitability. I suspect that those of my generation who came of age under martial law and fought it, who saw dozens of our comrades die, can do that with more equanimity than most, never having expected to live beyond twenty-five; every year and decade since has been a grace note, a blessing we have been careful not to waste. We are lucky to have come this far, and can leave without regret.

The Buddhists have what they call maranasati, the practice (says Google, meat-eating me being decidedly non-tantric) of contemplating one’s own mortality to cultivate mindfulness, reduce fear of death, and appreciate the present moment. The practical Swedes have döstädning, celebrated in The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter by Margareta Magnusson, a Nordic Marie Kondo who advises us to downsize and clean up our mess before we croak to save some grumpy nephew the trouble of sorting out which things go to the trash and which go to the resale shop.

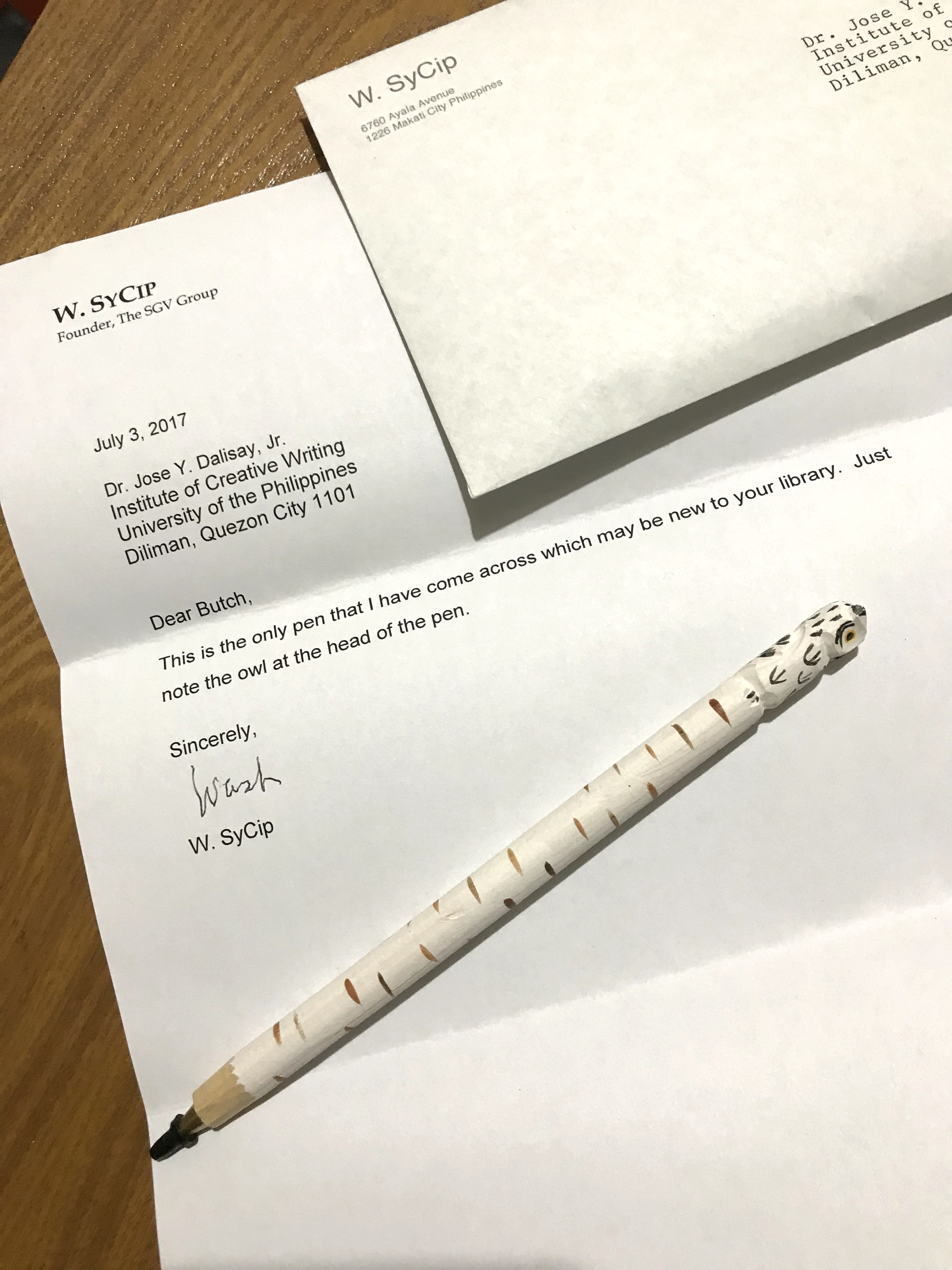

Speaking of which, my devotion to Japan-surplus stores and their wonderful bargains is tempered by the knowledge that most of these items were likely made available by the peculiarly Japanese practices of hikikomori, or withdrawing from society and living alone, and the even sadder kodokushi or “lonely death,” where the bodies and belongings of the forgotten might be found days after their passing. But then, as a collector of vintage fountain pens and antiquarian books, I am well aware that these precious objects have passed through many lives and survived their owners, and will certainly survive me, which is strangely reassuring. They offer proof of an afterlife—maybe not paradise, but the life of the people and things you leave behind.

In a way, death’s predictability (or the illusion thereof) is comforting, because we think we can therefore prepare for it, as for the coming of a friend who will lead us away by the hand, down to the smallest detail. Despite her surprisingly good health, my 97-year-old mother has written out her DNR instructions, and a year ago we made a light-hearted trip to the mall to pick out her funeral dress, in a deep, pacific blue. Well before my father died of an aneurysm almost thirty years ago—he was a chain-smoker and a candidate for early passage—I had written out a scene in my first novel where the protagonist comes home to his father’s wake, which was my way, the privilege of imaginative writers, of cushioning the real pain when it struck; when it did, I still wept like my father’s child.

I’m writing this because I’m actually not very good at dealing with death and processing grief, as detached or as flippant as I may sound about it. I avoid or don’t stay long at the wakes of friends because I tend to say the lamest things.

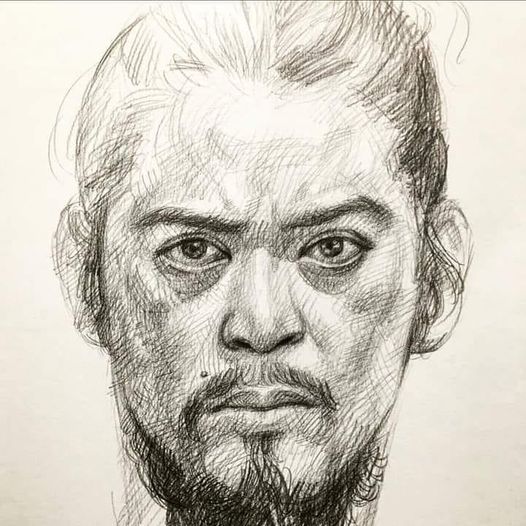

Last week I lost good friend—a high-school classmate named Don Rodis, brother to lawyer Rodel and producer Girlie, whom more people know—our Philippine Science High School batch’s livewire and indefatigably perfect host, to those visiting him in San Francisco. On vacation with his family in Los Cabos in Mexico, Don was strolling on the beach when a rogue wave known by the locals as the mar de fondo caught and swept him out to sea. Despite a massive search, his body has yet to be found. We are all stunned and awash with grief, but what struck me was how pretty that beach was from all the pictures, how blue and inviting its waters. And now I’ll say a stupid thing, for Don: rather than dying from a rocket to your head, or rotting from within, or freezing alone in Yamagata, sometimes we die in beauty’s arms.

(Don Rodis, 1954-2025, with his wife Jocelyn)