Penman for October 20, 2024

I’VE OFTEN remarked, in academic conferences, about the glaring absence of the sea in our mainstream and modern literature, beyond serving as a decorative backdrop or romantic element. I recently learned that this may not be so true of the native literatures of the Philippine South, for whose people the sea is their economic and cultural lifeblood, but for most of the rest of us, the only sea we’ll ever know is Boracay, or the Dolomite Beach.

That’s a sad thing when we consider that the Philippines—the world’s second largest archipelago after Indonesia—also has one of the world’s longest coastlines (over 36,000 kilometers), is rich in marine biodiversity, and can look back to a long, proud, and continuing seafaring tradition. Despite the alarming depletion of our marine resources due to overfishing and damage to marine ecosystems, we continue to rank high among the world’s fish producers; ironically, our fishermen are among our country’s poorest citizens. And for many decades now, the Philippines has sent out its seafarers to crew the ships of the world—over 550,000 of them last year, making up a fourth of all the world’s seaborne workers.

To go back even farther into the past, pre-Hispanic Filipinos built the balangay that helped populate Austronesia as well as the speedy warship, the caracoa; in Spanish times our ancestors built the galleons that crossed the oceans. In Moby Dick, Herman Melville referred to Filipinos aboard the whalers as “Manila men.”

Behind these figures runs a compelling human and social drama, but it’s a story largely unknown and untold to our own people, and what little we know is fading even faster as more of us leave our islands for the big cities, slowly but surely losing our personal connections to the sea. We encounter sea life only in the fish market or the seafood section of the grocery, or in tin cans; our children do not know the names of fish, which many now refuse to eat, in favor of sausages and noodles.

Thankfully, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) has done something critically important to fill this gap in our collective memory—by establishing a Museum of Philippine Maritime History (MPMH) that tells the story of our seafaring past. And it’s significant that this museum isn’t located in Manila, which would seem to be the logical first choice given Manila Bay and its port, but in Iloilo, which has also had a long and continuing affinity with the sea. Iloilo has historically supplied many if not most of the country’s seafarers to the global market. The city has a plethora of schools offering maritime courses, ensuring the continuity of talent.

I stumbled on the MPMH during a recent visit to Iloilo—among my favorite local destinations for all the obvious reasons (the food, the Esplanade, the heritage houses, the churches, the hospitality, the culture, and of course the people). The amazing boom it’s undergone over the past two decades under the sponsorship of former Sen. Frank Drilon and his local counterparts has dramatically transformed the city’s physical and economic landscape, but it hasn’t forgotten its past as it moves resolutely forward.

Iloilo has long been known as the city of museums. Aside from the Museo Iloilo and any number of restored mansions, it now boasts the Museum of Philippine Economic History, which chronicles the city’s and region’s central role in sugar, shipping, and commerce; the Rosendo Mejica Museum, which celebrates Iloilo’s journalistic heritage (and I’m proud to say that my wife Beng descends from a Mejica); and the Iloilo Museum of Contemporary Art, which places Iloilo squarely in the center of cutting-edge art production.

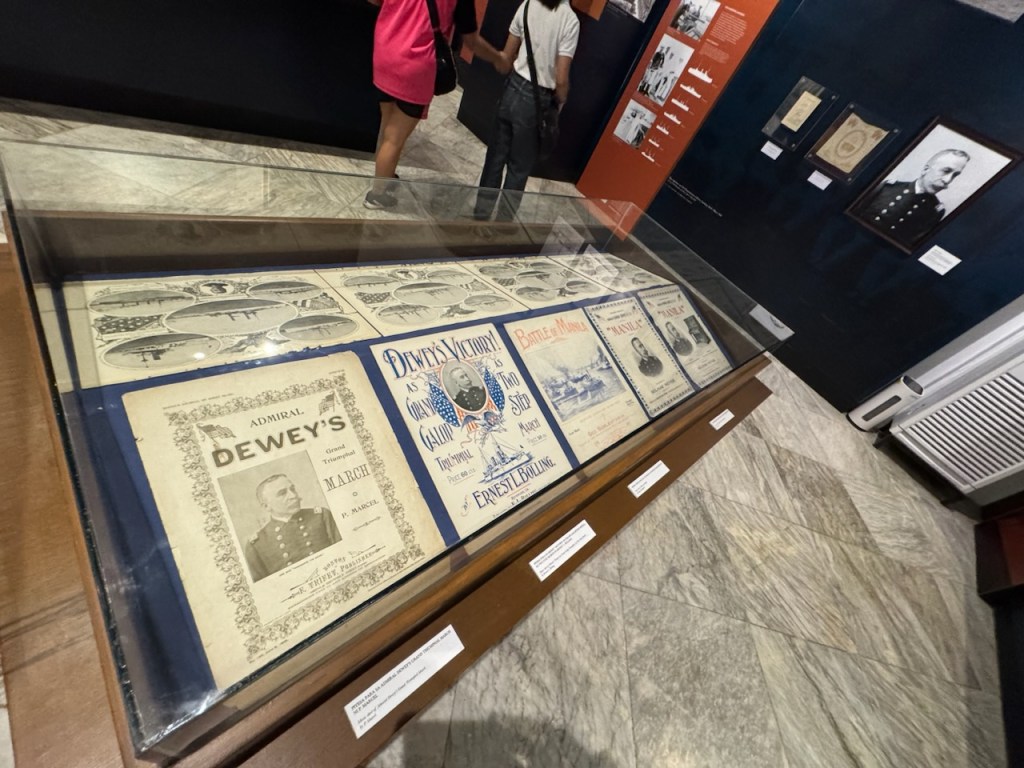

The MPMH, which opened in January 2023 at what used to be the Old Customs House on Calle Loney and Aduana in City Proper behind Sunburst Park, walks the visitor through exhibits covering the past until the Spanish era, and the American period to modern times. One very informative section presents the variety of Philippine boats (biray, casco, vinta, batil, etc.); scale models bring some to life. Key figures in our maritime history such as Luis Yangco (1841-1907), who had a shipping empire and supported the revolution are introduced. Historical photographs, posters, and other artifacts provide vivid visual proof of how vital the maritime industry was to our economy and society. Another panel notes the many waterborne festivals we Filipinos hold throughout the country, such as the Pista ‘Y Dayat in Lingayen, Pangasinan every May, and the Bangkero Festival in Pagsanjan, Laguna every March.

It’s not a huge gallery, and one wishes there were even more artifacts on display to ponder, but in terms of curation and presentation, the MPMH can hold its own, given its present limitations, against other international museums of its kind, with crisp, clear graphics, well-chosen items, and useful and interesting detail. (I’ve had the privilege of visiting the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich in the UK and the Museo Naval in Madrid, so as global standards go, those two maritime giants would be tough to match.) The MPMH’s best come-on—which probably accounted for the hordes of students present when we came by—is that it’s absolutely free, although donations are welcome. That’s a great start, with the kids, toward recovering our memory of the sea.

Penman for Monday June 5, 2017

Penman for Monday June 5, 2017