Penman for Sunday, February 8, 2026

HAVING NO idea how Gen Z people write love letters (and if they even do), I asked AI, and this is what it told me:

“Gen Z love letters are characterized by digital-native, emotionally fluent, and, often, casual expressions that prioritize vulnerability, mental health, and boundary-setting. They frequently use lowercase, rapid-fire, multi-message formats, and ‘ily’ (informal) or ‘love ya’ to avoid excessive intensity. Common themes include a rejection of traditional, performative romance in favor of ‘soft launching’ relationships (gradually revealing a partner online) and a focus on authenticity over aesthetics.”

I have to confess that the answer left me feeling much relieved to be 72 years old and increasingly irrelevant. If I were young and seventeen today but with the mind and heart that I had back in 1971, I seriously doubt that I could make a significant connection to the Gen Z girl of my dreams, from whom I would have drawn derisive laughter for a long, convoluted, meandering letter asking for a first date (I will neither confirm nor deny that this actually happened). I may have lacked in “emotional fluency,” but certainly not for words, which were all I had when, in 1973, I met a pretty girl named Beng and pounded her with prose, in my crabbed, ungainly penmanship using a technical pen; within months we were married (and still are, 52 years later).

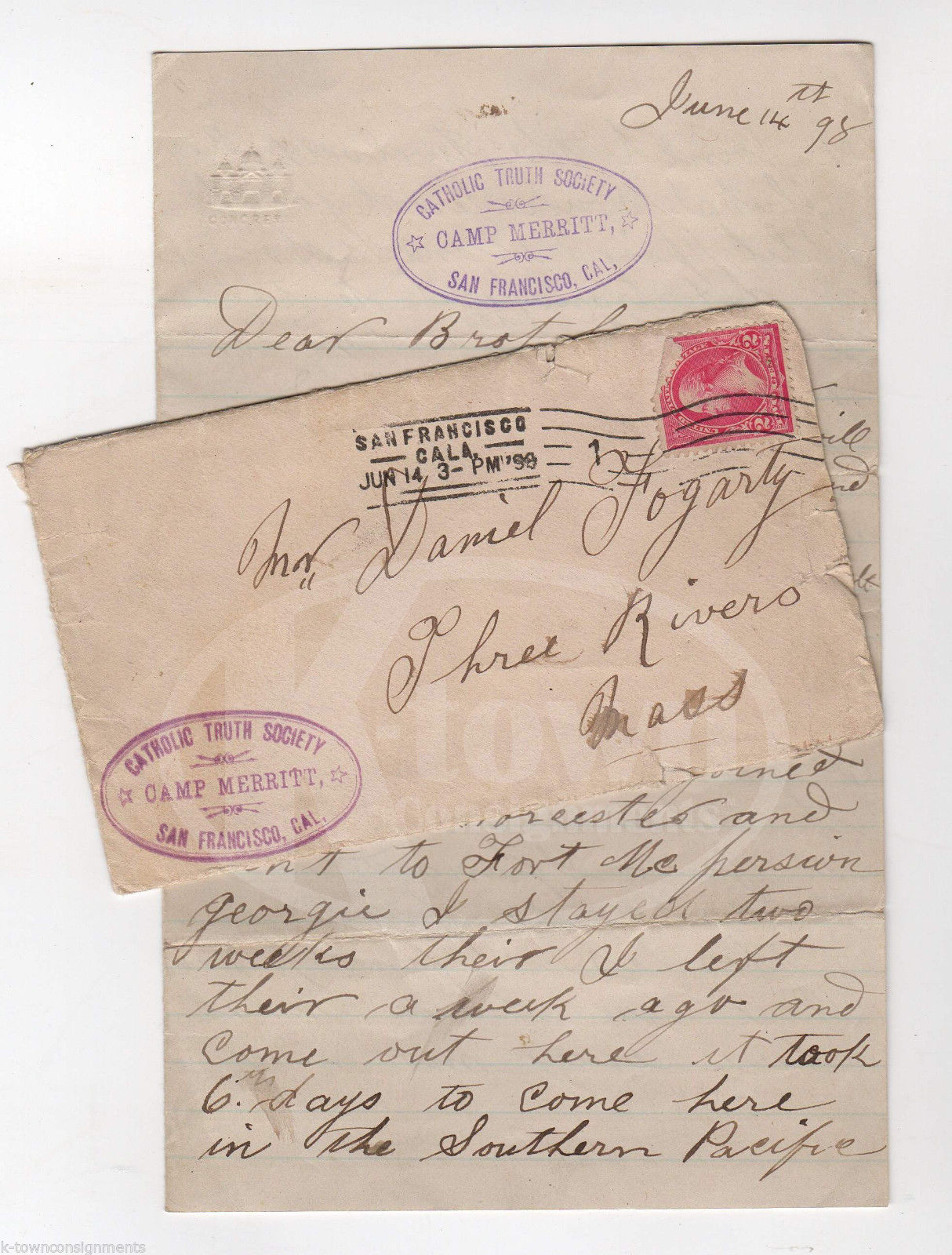

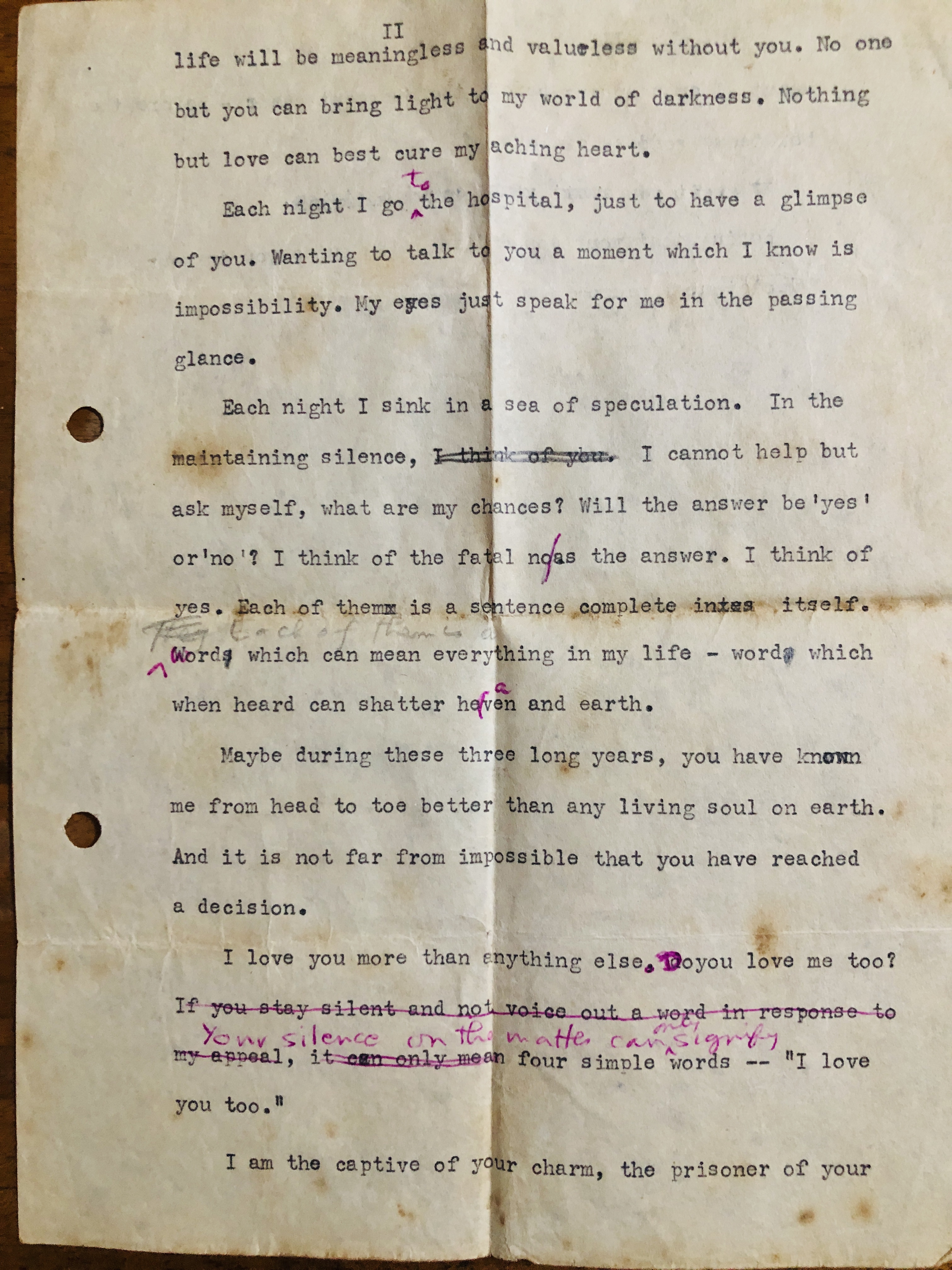

Time was when love needed to be declared in big, bold, wet letters—and I don’t mean letters as in ABC, but letters as in pages of paper filled with scribbled and impassioned professions of affection, sometimes of hurt, sometimes of longing, but always of desire for the addressee. Setting everything else aside, overtaken and overwhelmed by this most urgent need, a man or a woman sat at a desk—or kitchen table, or any hard surface on a beach or a moving vehicle—and put pen to paper to release a flood of pent-up emotion.

It all came down to the same three-word idea: “I love you” (sometimes, or more often, with a fourth word, “but”). As with love poems, some letters were better, more unique, more persuasive than others; most, in hindsight, were likely mawkish or mediocre. But rarely—except perhaps to writers keen on grammar and style—did literary merit matter, neither to sender nor receiver; the profession of love alone was monumental enough. Because it was handwritten and signed, it was personal and deliberate, a statement of commitment impossible to deny.

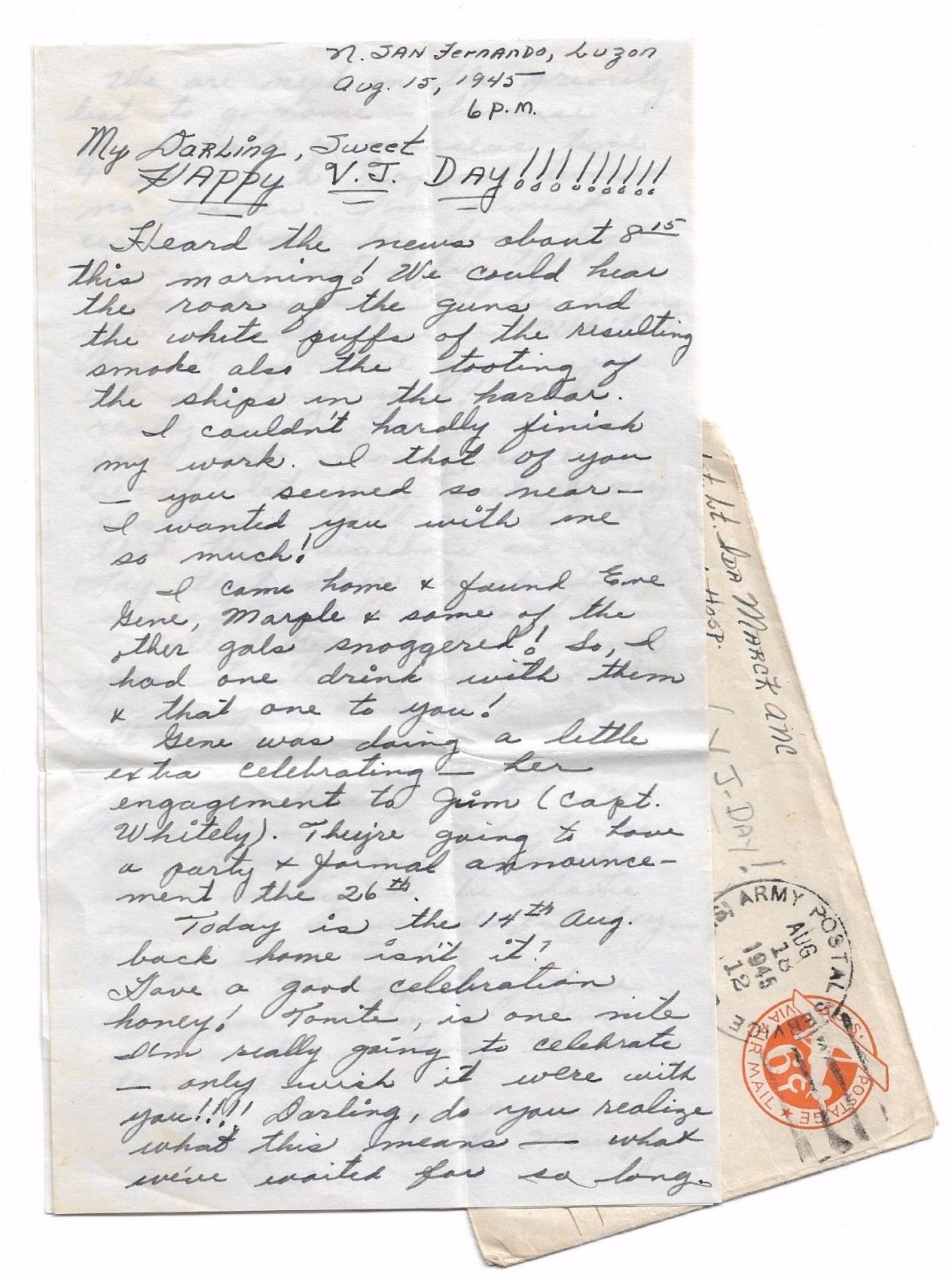

Indeed what was thought to be intimate and ephemeral sometimes became history. Little did lovers realize or perhaps care they would become famous, and that their private correspondence would become known—thankfully not to their peers but to posterity and the critical judgment of strangers.

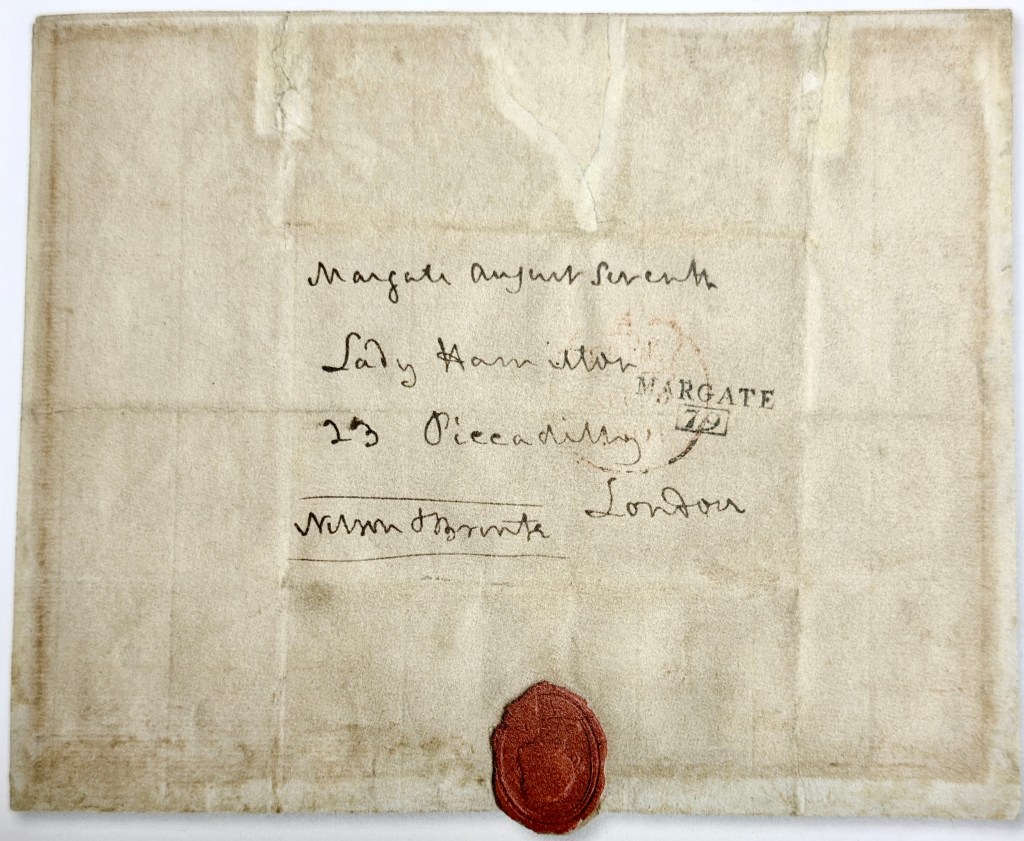

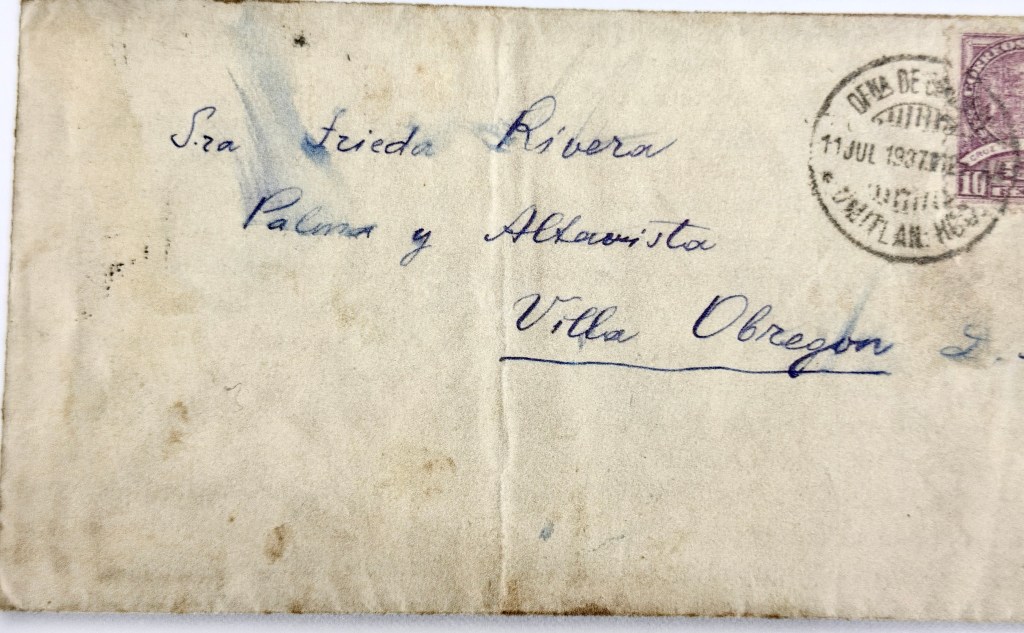

In one of the books I treasure most in my library titled The Magic of Handwriting: The Pedro Correa de Lago Collection (Taschen, 2018), two envelopes offer proof of love affairs—illicit in this case, as all the parties concerned were married to someone else—between Lord Nelson and his mistress Lady Hamilton, and between the revolutionary Leon Trotsky and artist Frida Kahlo (who had given the outcast Trotskys refuge in her home).

This was the same free-spirited Frida who would write her husband Diego Rivera that “Nothing compares to your hands, nothing like the green-gold of your eyes. My body is filled with you for days and days. You are the mirror of the night. The violent flash of lightning. The dampness of the earth. The hollow of your armpits is my shelter. My fingers touch your blood. All my joy is to feel life spring from your flower-fountain that mine keeps to fill all the paths of my nerves which are yours.” (To be fair to Frida, Diego was far more liberal with his vagrant attentions.)

In one of literary history’s worst-kept secrets, Vita Sackville-West would write to Virginia Woolf that “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia… I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your undumb letters, would never write so elementary a phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a little gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it should lose a little of its reality…. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any more by giving myself away like this — But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defenses. And I don’t really resent it.”

Jose Rizal’s letters to Leonor Rivera were reportedly all burned, but as Ambeth Ocampo notes, two of her letters to Rizal survive, in which she uses the pseudonym “Taimis” and tells him that “I was very much surprised that you had a letter for Papa and none for me; but at first when they told me about it I did not believe it, because he did not expect that a person like you would do such a thing. But later I was convinced that you are like a newly opened rose, very flushed and fragrant at the beginning, but afterwards it begins to wither…. Truly I tell you that I’m very resentful for what you have done and for another thing that I’ll tell you later when you come.” We know how that story ended, with the both of them going their separate ways and marrying another, although Leonor was said to have pined for Pepe to the end.

Again thanks to Ambeth, I can quote Manuel L. Quezon’s 1937 letter to his wife Doña Aurora, where he engages in what today might be called “gaslighting”:

“Darling, I am still wondering if you really think that I love you less. Please don’t doubt me, my love has never changed from the first day I have realized that I was in love with you. I have my weakness as you know, but, dear, it’s all superficial and you know also, that, except for the case of that bailarina, my weaknesses in this respect have not been serious. When you married me, you were frankly informed by me of my shortcomings. I did not want to deceive you by promising something that I could not fulfill. After we have been married you have placed [me], sometimes, in a position when I thought that it was better that I should not confess to you what I had done that might hurt your feelings, but I want you to know that whenever such a thing took place I have felt very bad about it, because nothing I dislike more than not to tell the truth and I always resented the fact that you should prefer to put me in such a situation, thus making me almost hate myself.”

That would still have been more preferable than receiving this ardent letter from a king, and falling for him: “But if you please to do the office of a true loyal mistress and friend, and to give up yourself body and heart to me, who will be, and have been, your most loyal servant, (if your rigour does not forbid me) I promise you that not only the name shall be given you, but also that I will take you for my only mistress, casting off all others besides you out of my thoughts and affections, and serve you only…. And if it does not please you to answer me in writing, appoint some place where I may have it by word of mouth, and I will go thither with all my heart. No more, for fear of tiring you.” The recipient, Anne Boleyn, lost her head in more ways than one, and the sender, Henry VIII, went on to court her successor, Jane Seymour, who wisely returned his love letter unopened—sparking his interest in her even more intensely.

The letter I found too coarse and too embarrassing (brimming with scatological detail) to even quote was written by James Joyce to his wife Nora, but the technologically adept will surely find it online.

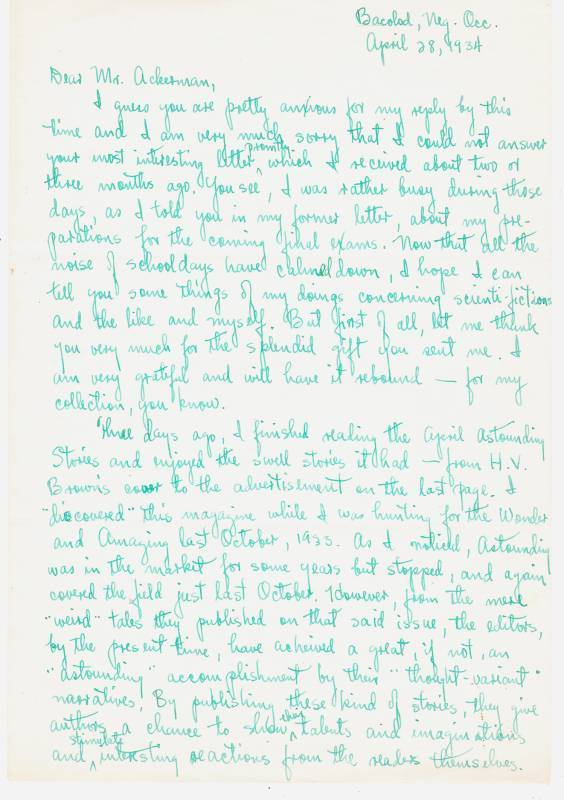

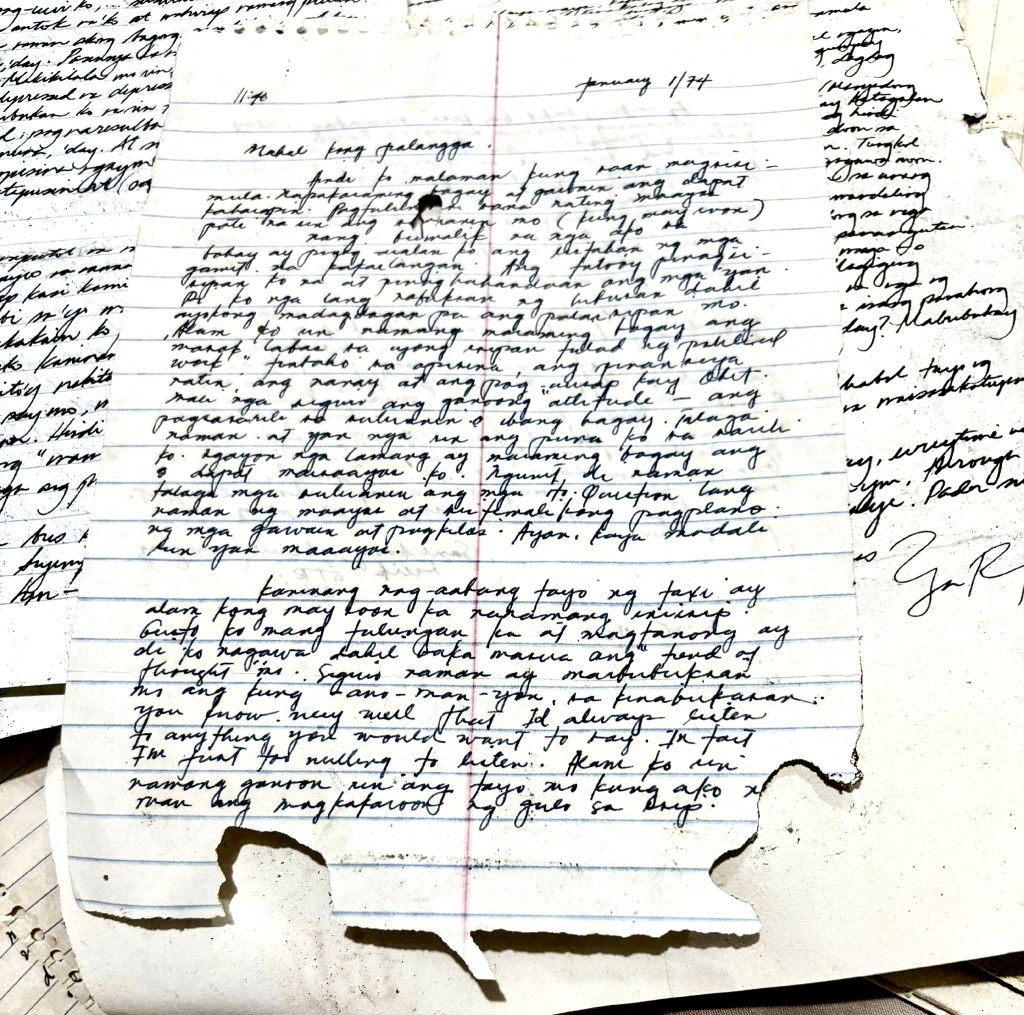

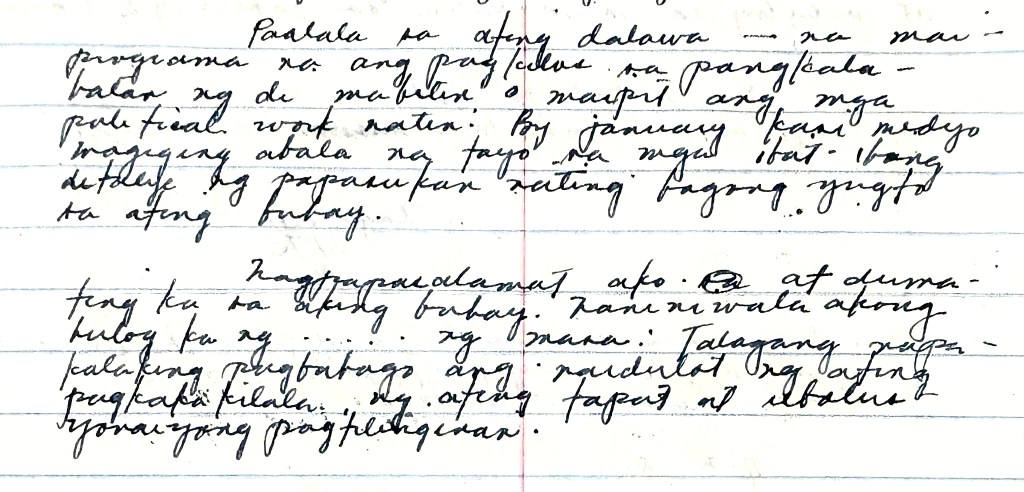

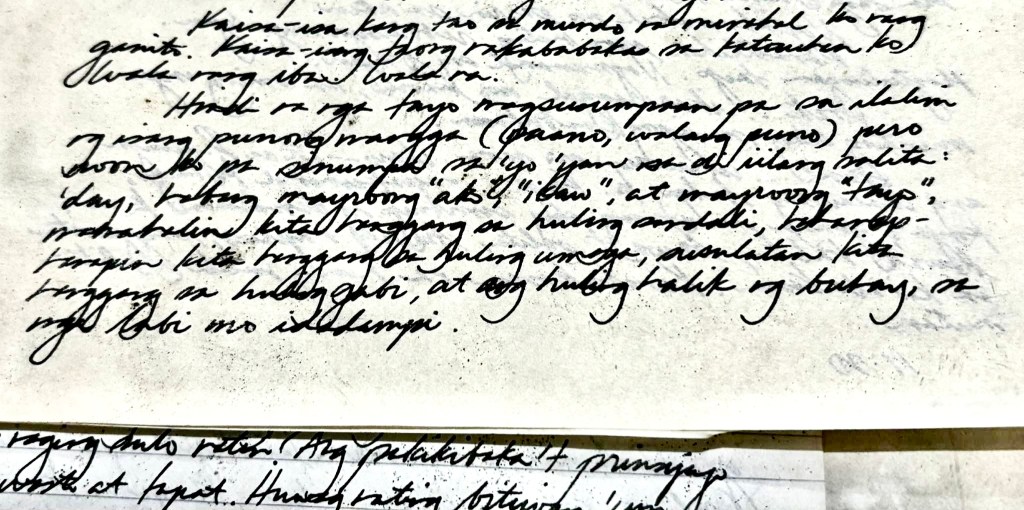

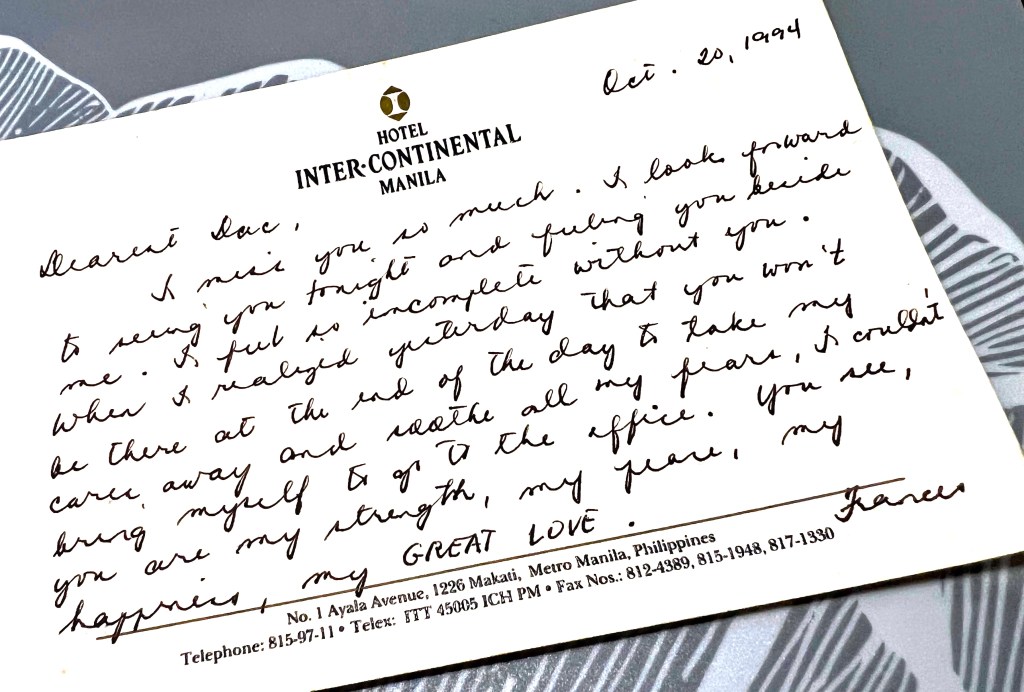

My own letters to Beng, and hers to me, are stored in a moldering box that occasionally gets lost and then resurfaces in a year or two, and when we go over them we laugh and cringe at their melodramatic prolixity, as though life itself would run out soon (as it did for many of our generation, under the cloud of martial law, and thus the urgency).

So how do the love letters that we—perhaps the last of the art’s practitioners—have written stack up against history’s and literature’s most memorable? But first, who are “we?”

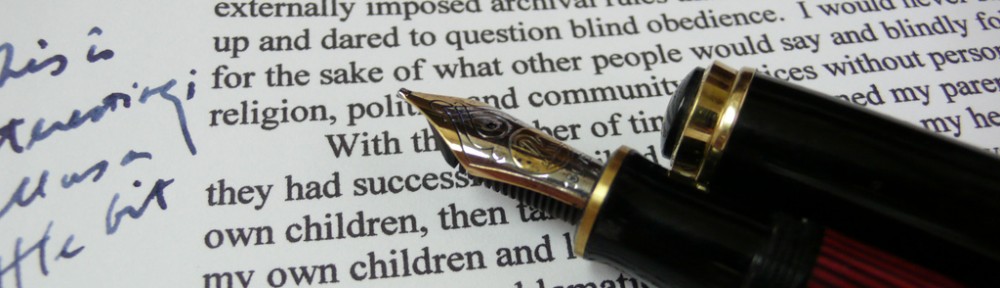

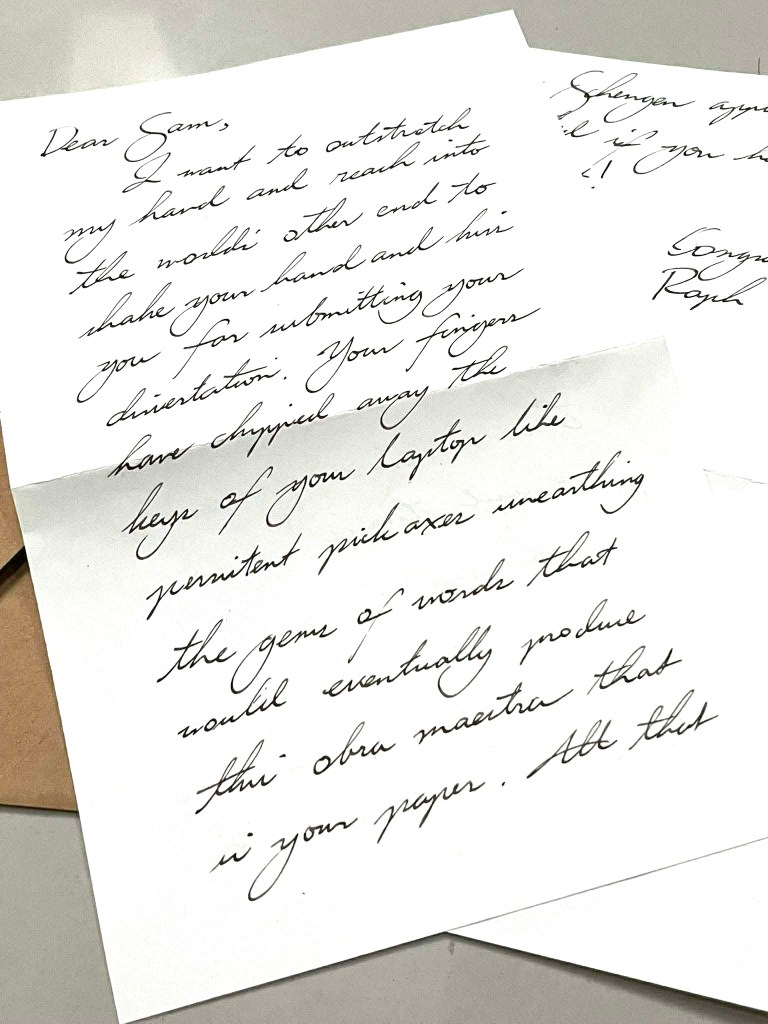

The immediate “we” are members of our Fountain Pen Network-Philippines who still value and use pens for handwritten communication, beyond signing checks and office forms. Old fogeys like me naturally fall into that category, but surprisingly, given the fountain pen’s and handwriting’s resurgence as a form of protest, if you will, against digital homogenization, many younger people, even some Gen Z’ers, have taken up the cause. Ballpoints are all right—but there’s still nothing better than a vintage fountain pen nib, which flexes with pressure and gives the inked line more character, to convey emotion.

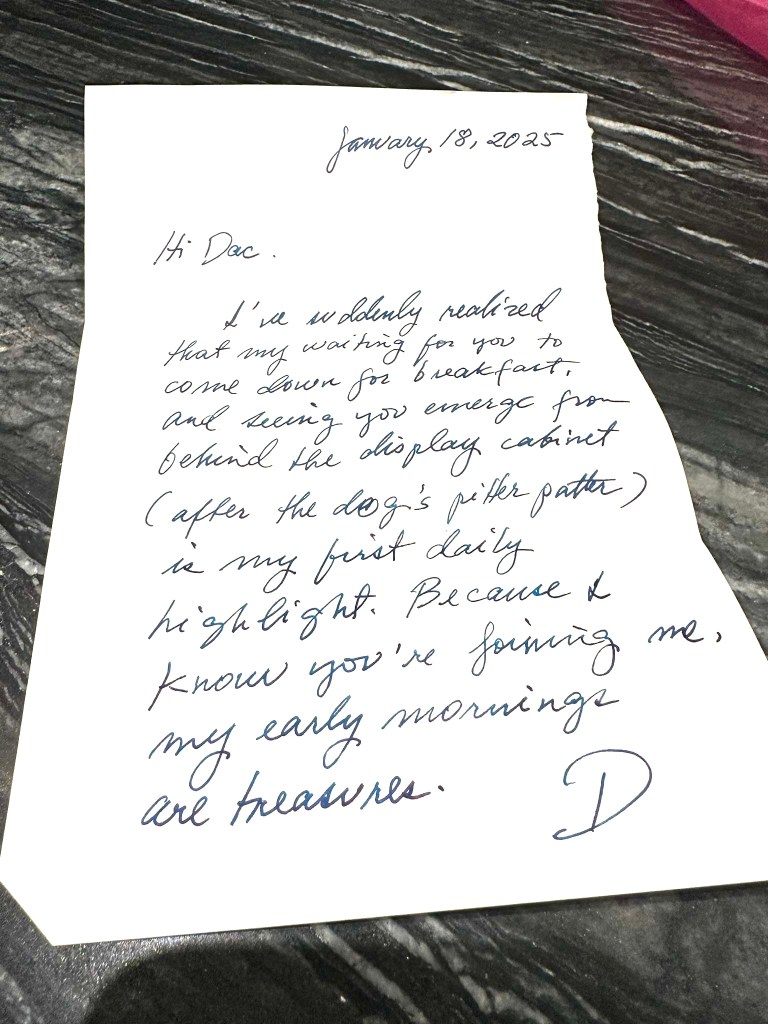

From what I’ve gathered, the best love letters people write go far beyond the often vapid promises and profuse assertions of courtship. They’re unbidden reminders and reassurances of affection, a note quietly written in the morning, a message of congratulations. This, too, is love with a deeper, more hushed voice that comes with maturity and assurance.

I should take my own advice and write Beng more love letters with my hundreds of pens, every single act of which would validate that pen’s existence and probably exorbitant purchase price. I should employ all the colors of ink stored in the dozen bottles that crowd my desk to express love in all its shades and moods, in the same spirit that Robert Graves wrote: “As green commands the variables of green, so love my loves of you.”

But sadly this old man’s fingers have become cramped from being curled too long over keyboards, and can barely finish a page of handwriting before tiring. So instead—though not quite a Gen Z’er accustomed to “lowercase, rapid-fire, multi-message formats”—I write articles like this and stories on Facebook that suggest, ever so obliquely, how central she remains to my life, albeit in Georgia 12 points and .DOCX rather than flowing script. My idle pens, dear Beng, are like the books I’ve yet to write for you, the words still forming in the opaque ink, like the colorful and wide umbrellas I keep buying to shield you with, waiting for rain. So there, and Happy Valentine’s.

Penman for Monday, December 24, 2018

Penman for Monday, December 24, 2018