Penman for Monday, September 14, 2015

A COUPLE of months ago, I wrote a piece here about the Nobel prizewinning novelist Ernest Hemingway’s brief visit to Manila in February 1941. When my friend Dr. Erwin Tiongson read that, he sent me more materials about that brief encounter between the literary titan and his local readers, including a reference to a second visit by Hemingway on May 6, presumably on his way back to the US.

(Now based in Washington, DC and a professor of economics at Georgetown, Erwin was recently in Manila himself with his journalist wife Titchie for a vacation and a series of presentations about their fascinating project of historical sleuthing, which you can find online at https://popdc.wordpress.com. I’ll be writing more next time about the Tiongsons and their meeting with Teresa “Binggay” Montilla, the granddaughter of Philippine Commissioner to Washington Jaime C. de Veyra and his remarkable wife Sofia, about whom the Tiongsons unearthed a trove of interesting historical material.)

Meanwhile, I’d like to share a bit of what Erwin sent me, taken from the American Chamber of Commerce Journal of June 1941, unbylined but attributed to the journal’s publisher and editor, Walter Robb. It’s an account of Hemingway as a man and a regular guy—41 years old, 225 pounds, black-haired and black-eyed, whose Spanish “runs along like a garrulous brook… words never fail him, nor picturesque phrases. He likes singing Basque folk songs and he and the Basques seeing him off on the clipper sang them all the way from the Manila Hotel to Cavite….”

Farther down that article, the reporter notes that “It’s easy to get Hemingway’s autograph, just ask for it and have a pen handy…. He autographed many copies of his book while he was in town. The book has been pirated at Shanghai, of course; when one of these spurious copies, no royalty to Hemingway, came along for autographing, Hemingway grinned and autographed it. He likes to use a standard typewriter in his work, which he does of mornings, but For Whom the Bell Tolls was not written that way: it was written in longhand. Hemingway uses a heavy stub fountain pen and this longhand of his, as bold as sword strokes, but honestly legible and well-spelled, flows across the paper as straight as a line.”

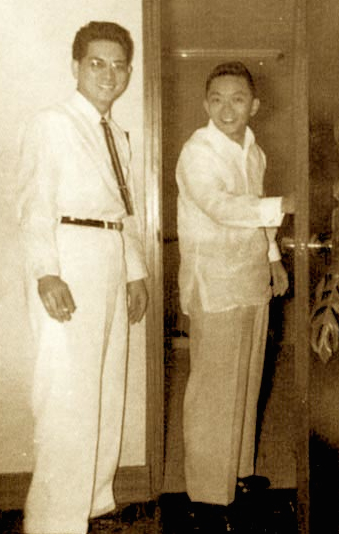

I was, of course, attracted to that passage because it particularly mentioned Hemingway’s pen, which I would have dearly loved to see; but also, it talked about Hemingway signing books, which reminded me of a photograph I adverted to in my earlier column, showing Hemingway signing a book for a young Filipino writer named Nestor Vicente Madali Gonzalez, who in early 1941 would have been no more than 25 years old. I’d seen that picture in NVM’s house in UP when he was alive, and had worried that it might have been lost when the house burned down. But after my piece came out, I was happy to hear from NVM’s youngest daughter Lakshmi that she had posted a copy of it on her Facebook page, and I hope she doesn’t mind if I repost it here—Ernest meets Nestor, you might say.

Speaking of NVM Gonzalez, the literary community marked the centenary of his birth last Tuesday, September 8, in an evening of tributes at the Executive House at the University of the Philippines in Diliman organized by Prof. Adelaida Lucero. NVM, of course, taught with UP—among many other universities here and in the United States—for many years despite the fact that he never completed his bachelor’s degree. As director of the UP Institute of Creative Writing, I was asked to say a few words at the testimonial dinner, which was attended by NVM’s widow Narita, and here’s a reconstruction of the remarks I made:

“NVM and I were born only 60 kilometers away from each other in Romblon—he on Romblon Island and I on neighboring Tablas—but also almost 40 years apart, and I never had the good fortune of being his student in UP. It’s actually my wife Beng who’s been closer to the Gonzalezes, having been Narita’s student at UP Elementary. But I had the chance to meet NVM and to enjoy his company when he returned to UP in the 1990s as International Writer-in-Residence under the auspices of what was then the UP Creative Writing Center. I had the honor of drafting his nomination as National Artist, signed by then Dean Josefina Agravante.

“Franz Arcellana was my teacher, and Bienvenido Santos and Greg Brillantes were my literary models; but it was NVM who hung out with us, whom we had fun with in our workshops in Baguio and Davao. And as advanced as he was in years, he was forward-looking and eager to learn. I remember running into him once in what was then the SM North Cyberzone, and I asked him what he was doing there. ‘I’m looking for a book on multimedia!’ he told me with that twinkle in his eyes.

“We didn’t always agree, but the one thing I can say about NVM is that he never threw his weight around, never pulled rank on us his younger associates, never thundered about how much older or more accomplished he was to suggest why he was right and we were wrong, despite his obvious seniority in age, experience, and wisdom. We appreciated that. That’s why, in the foreword to a book of essays by his friends that I edited after his death in 1999, I said that some writers are respected and admired, and others are loved. NVM was both.”

The celebration of NVM’s centenary won’t stop with that dinner—which also saw the launch, by the way, of new books on NVM: his poems, edited by Gemino Abad, and a Filipino translation of Seven Hills Away by Edgardo Maranan, published by the UP Press and the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, respectively. At the end of this month, the UP Department of English and Comparative Literature will hold an exhibit of photographs of and works by him. His son Myke, based in the US, is organizing a fiction-writing workshop in January, the first half to take place in Diliman and the other in Mindoro, and the UPICW will be helping Myke out with that project.

It never ceases to amaze me how a web of words (make that a Worldwide Web, these days) can bring people together across the miles and years.

[Photo courtesy of Lakshmi Gonzalez-Yokoyama]

Penman for Monday, February 23, 2015

Penman for Monday, February 23, 2015