Qwertyman for Monday, May 13, 2024

IN MY long life as a professional writer—aside from being a fictionist, journalist, and academic—I’ve occasionally been asked to write books for both private and public institutions and individuals, usually to commemorate an important milestone. My clients have included banks, power and energy companies, accounting firms, NGOs, business tycoons, politicians, and thinkers.

While it’s a job, it’s also been a great learning experience for me, particularly when I’ve had to deal with topics like oil exploration, steel manufacturing, and geothermal energy. I begin to understand how things really work in our economy and society, seeing the cogs and wheels that turn industry, create jobs, and produce things people need. I meet people I never would have run into otherwise, people with interesting stories to tell about themselves and their work.

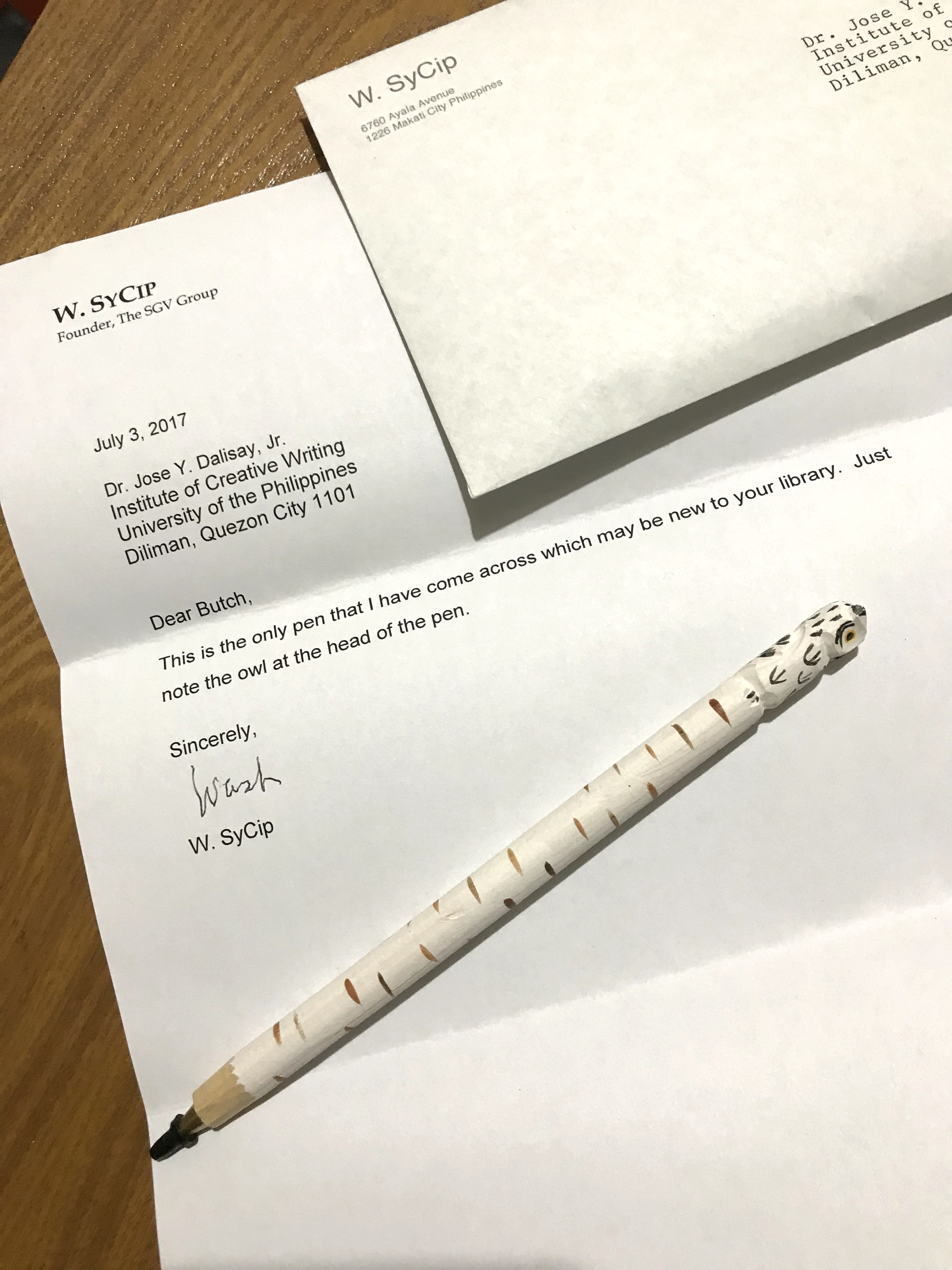

Probably the most famous of those people was Washington SyCip, the legendary founder of SGV & Co., once one of Asia’s largest and most highly respected accounting firms, whose biography Wash: Only a Bookkeeper I wrote back in 2008. When people tell me how boring the lives of accountants must be, I tell them the story of Wash, who wasn’t just an academic prodigy who graduated summa cum laude from college at 17, but who also served as a US Army codebreaker in India in the Second World War. Granted, not many accountants lead lives as colorful as Wash’s, but to suggest that there’s no drama in accountancy is certainly mistaken.

I discovered this in my latest (and very likely my last) commissioned book, A Century of Philippine Accountancy, which will be launched this week by the Philippine Institute of Certified Public Accountants (PICPA) Foundation. The book is a compendium of both big and small stories, an institutional history that also delves into the personal struggles and triumphs of key people in the industry.

The centennial book comes a bit late, because the Philippine accounting profession formally traces its beginning to March 17, 1923, when the Sixth Philippine Legislature passed Act No 3105, “An act regulating the practice of public accounting; creating a Board of Accountancy; providing for examination, for the granting of certificates and the registration of Certified Public Accountants; for the suspension or revocation of certificates and for other purposes.” Six years later, the PICPA was established within the private sector to represent professional interests.

Of course, some form of bookkeeping was being practiced in the Philippines long before that. Given the Philippines’ vigorous trade with other countries such as China even before Spain’s arrival in 1521, there must have been some early form of record-keeping maintained by both natives of the islands and their foreign trading partners. Accounting in early China was said to have reached a peak during the Western Zhou dynasty (1100-771 BC); the Chinese developed sophisticated methods of accounting to keep track of such basics as revenues, expenditures, salaries, and grain. In Spain, regulations began to be applied regarding the accountability of companies starting with Queen Juana and her son Emperor Charles V in the 1500s. Manila’s galleon trade with Mexico, which lasted from 1565 to 1815, required meticulous bookkeeping, and archival records still exist of the cargo manifests of the galleons; these records show, for example, that audits of the ships’ cargo revealed discrepancies in capacity that suggested smuggling (whereby space meant for such necessities as water was reduced to make way for profitable goods).

Since 1923, the profession has grown in the Philippines by leaps and bounds to nearly 200,000 registered CPAs, employed in over 8,000 firms and partnerships. Based on the number of Publicly Listed Companies (PLCs) they audit, six firms dominate the industry: SGV & Co. (Ernst & Young); Isla Lipana & Co. (PricewaterhouseCoopers Philippines); R.G. Manabat & Co. (KPMG Philippines); Reyes Tacandong & Co. (RSM Philippines); Punongbayan & Araullo (Grant Thornton Philippines); and Navarro Amper & Co. (Deloitte Philippines). In keeping with the times, many local firms have affiliated themselves with large global partners to avail themselves of the latest technology and expertise. (For a bit of trivia, the first Filipino CPA was Vicente F. Fabella, the founder of what is now Jose Rizal University.)

The profession is governed by the Board of Accountancy (BOA), which administers the CPA Licensure Exam at least once a year. The BOA in turn is supervised by the Professional Regulatory Commission, along with other professional boards. The BOA and PRC work closely with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which is responsible for ensuring the integrity of the country’s financial system and its institutions.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis highlighted the importance of quality assurance and adopting international financial reporting standards in accounting. With the help of the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, the major players in the profession—PICPA, BOA, PRC, and SEC, among others—undertook studies to reform the industry, resulting in the Philippine Accountancy Act of 2004. The SEC also initiated an Oversight Assurance Review to extend and strengthen reforms further. What the book chronicles most significantly, according to former SEC Commissioner Antonieta Fortuna-Ibe, is the Filipino CPA’s rise to global respectability and prominence, because of the industry’s relentless efforts to raise its standards and to keep pace with the latest developments in financial technology. Ibe stood at the vanguard of many basic reforms in Philippine accountancy, and was behind the push for a book to mark their centenary.

The profession will need to adapt to the ever-changing financial landscape. As SGV’s Wilson Tan puts it, “While we have yet to see how new technologies such as the Metaverse and the integration of AI into work applications will impact the accounting profession, CPAs of the future will need to likewise evolve their skills and capabilities. Foundational changes will need to be made in the curriculum to integrate learning that encompasses non-financial reporting matters, use of technology, data, and analytics, and cybersecurity, among others.”

Personal integrity, as ever, lies at the bedrock of accountancy. The BIR’s Marissa Cabreros reminds everyone that “Every CPA being asked to sign a financial statement must give weight to the purpose of their signature. If it has your signature as a CPA, we expect that you reviewed and recorded that properly. But unfortunately, sometimes lapses happen and CPAs forget what they signed for. An accountant must always have the importance and value of her signature in her heart.” Wash SyCip could not have put it any better.

Accountants and other members of the public interested in getting a copy of the book can email Lolita Tang at lolitatang@yahoo.com for more information.