Penman for Sunday, November 2, 2025

IT WILLl be remembered as one of the largest, most complex, possibly most impactful—and yes, also most expensive and controversial—showcases of Filipino cultural and intellectual talent overseas, and above and beside all else, that fact alone will ensure that few things will remain the same for Philippine literature after Frankfurt 2025: it will be remembered.

Last month—officially from October 14 to 19, but with many other related engagements before and after—the Philippines attended the 77th Frankfurter Buchmesse or FBM, better known as the Frankfurt Book Fair, in a stellar role as its Guest of Honor or GOH. Accorded yearly to a country with the talent, the energy, and the resources to rise to the challenge, GOH status involves setting up a national stand showcasing the best of that country’s recent publications, filling up a huge national pavilion with exhibits covering not only that country’s literature but also its music, visual art, film, food, and other cultural highlights, presenting a full program of literary discussions, book launches, off-site exhibits, and lectures, and, of course, bringing over a delegation of the country’s best writers and artists.

It’s as much a job as it is an honor. Past honorees have predictably come mainly from the West, such as France (2017), Norway (2019), Spain (2022), and Italy (2024); only once before was Asia represented, by Indonesia in 2016. Little known to many then, Sen. Loren Legarda—the chief advocate for the arts and culture in the government—had already broached the idea of pushing for the Philippines as GOH in 2015. It took ten years, with a pandemic and two changes of government intervening, but Legarda finally secured the funds—coursed through the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the National Book Development Board—for us to serve as GOH this year, announced a year earlier.

The Filipino delegates, over a hundred writers and creatives and as many publishers and journalists, took part in a program of about 150 events—talks, panel discussions, demonstrations, book launches, and performances—and ranged from Nobel Peace Prize winner and journalist Maria Ressa and National Artists Virgilio Almario, Ramon Santos, and Kidlat Tahimik to feminist humorist Bebang Siy, graphic novelist Jay Ignacio, poet Mookie Katigbak Lacuesta, and fellow STAR columnist AA Patawaran.

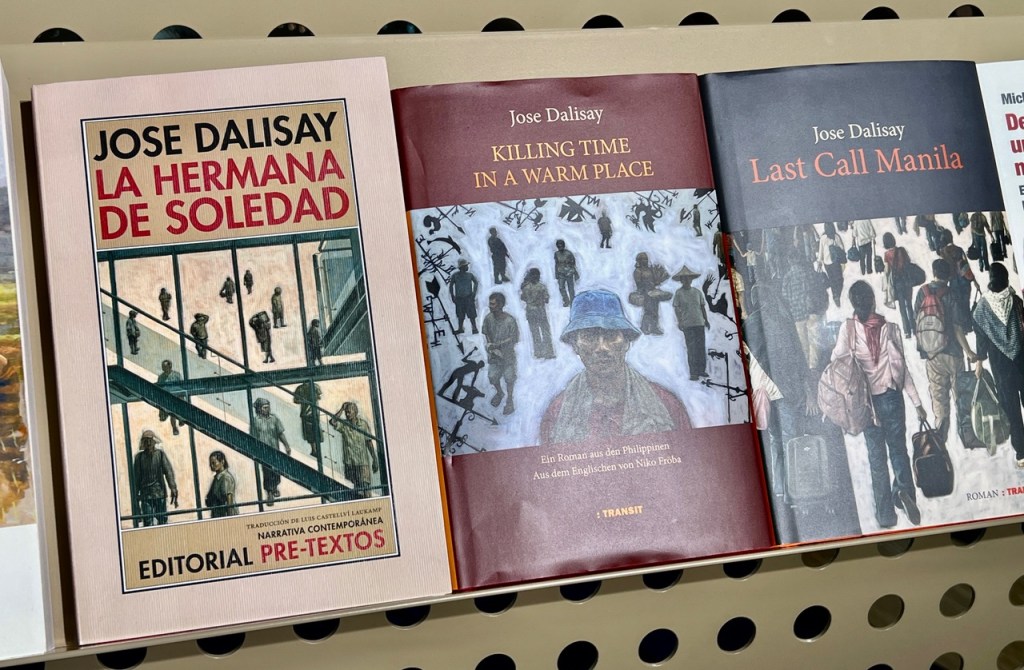

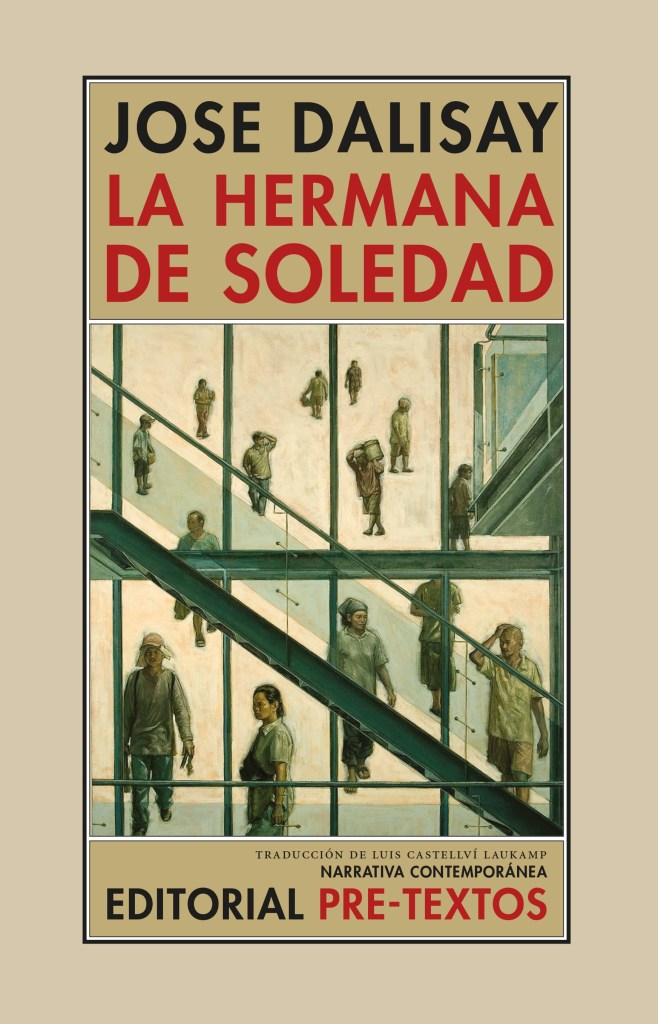

It was my third FBM, having gone for the first time in 2016 and then again last year, when the German translations of my novels Killing Time in a Warm Place and Soledad’s Sister were launched. This year, it was the Spanish translation of Soledad that was set to be launched at Frankfurt’s Instituto Cervantes.

Those two previous exposures allowed me to appreciate our GOH role for what it was—a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to put our best foot forward on the global stage. What began in the 1980s as a tiny booth with a few dozen books—which it still was when I first visited nine years ago—had become a full-on promotional campaign, not for the government (which did not object to outspoken critics of authoritarianism being on the delegation) and not even just for Philippine books and writers but for the Filipino people themselves.

Six out of my eight events took place outside the FBM—two of them involving side-trips to Bad Berleburg in Germany and Zofingen in Switzerland—to bring us closer to local communities interested in what Filipinos were writing and thinking. Indeed my most memorable interactions were those with local Pinoys and with ordinary Germans and Swiss who asked us about everything from the current state of affairs (the resurgence of the Right in both the Philippines and Europe, Marcos and Duterte, the threat from China, the corruption scandal) to Filipino food and culture, the diaspora, the aswang, and inevitably, Jose Rizal, who completed the Noli in Germany and in whose tall and broad shadow we all worked.

Everywhere we went, in Frankfurt and beyond, the local Pinoy community embraced us, eager for news from home and proud to be represented, to hear their stories told in words they themselves could not articulate. “I’ve been living a hard life working here as a nurse in Mannheim,” Elmer Castigador Grampon told me, “and it brings tears to my eyes to see our people here, and to be seen differently.”

A German lady accosted me on the street outside the exhibition hall and asked if I was the Filipino she had seen on TV explaining the Philippines, and we had our picture taken. A German author in his seventies, Dr. Rainer Werning, recounted how he had been in Manila during the First Quarter Storm and the Diliman Commune, had co-authored two books with Joma Sison since the late 1980s, and had described the Ahos purge in Mindanao and similar ops in other parts of the islands as the most tragic and saddest chapter in the history of the Philippine Left . A sweet and tiny Filipina-Swiss lady, Theresita Reyes Gauckler, brought trays of ube bread she had baked to our reception in Zofingen (the trays were wiped out). Multiply these connections by the hundreds of other Filipinos who participated in the FBM, and you have an idea of the positive energy generated by our visit.

From our indefatigable ambassador in Berlin, Susie Natividad, I learned about how Filipino migrant workers have to learn and pass a test in German to find jobs in Germany, a task even harder in Switzerland, where Swiss German is required. Despite these challenges, our compatriots have done us proud, as the maiden issue of Filipino Voices (The Ultimate Guide to Filipino Life in Switzerland) bears out.

The FBM was as much a learning as it was a teaching experience for us, for which we all feel deeply grateful. By the time our group took our final bows on the stage in Zofingen—a small Swiss city that hosts writers from the GOH after the FBM as part of its own Literaturtage festival—I felt teary-eyed as well, amazed by how a few words exchanged across a room could spark the laughter of recognition that instantly defined our common humanity.

I am under no illusion that GOH participation will dramatically expand our global literary footprint overnight, but it has created many new opportunities and openings for our younger writers to pursue in the years to come. It is a beginning and a means, not an end. The greater immediate impact will be to spur domestic literary production and publishing, to have a keener sense of readership, and to encourage the development of new forms of writing.

Sadly, a move to boycott the FBM by Filipino writers protesting what they saw to be Germany’s complicity with Israel’s genocidal war in Gaza has also impacted our literary community. (For the record, there were Palestinian writers—and even an Iranian. delegation—at the FBM, with whom Filipino writers interacted in a forum. There was also a Palestinian book fair across the fairgrounds.)

I have long taken it as my mission to promote an awareness of our work overseas and had opposed the boycott from the very beginning for reasons I have already given many times elsewhere. Many hurtful words have been spoken and many friendships frayed or broken, to which I will add no more, except to quote the Palestinian-Ukrainian refugee Zoya Miari, who visited the Philippine pavilion and sent our delegates this message afterward:

“I’m on my way from Frankfurt back to Zurich, and I’m filled with so much love that I can’t stop thinking about the love I felt in the Philippine Pavilion. I came back today to the Pavilion to say goodbye, not to a specific person, but to the whole community. This space became a safe space for me, one where I deeply felt a sense of belonging.

“I’m writing these words to thank you and your people for creating a space where

I, where we, felt heard and seen. That in itself is such a powerful impact. I know some people decided to stay in the Philippines to show support for the Palestinians, and I want to say that I hear and see them, and I thank them. And to those who decided to come, to resist by existing, by speaking up, by showing up, by connecting the dots, by being present and by sharing stories, I also hear you, see you, and deeply thank you.

“We all share the same intention: to stand for justice, to fight against injustice, and we’re all doing it in the best way we know how. I truly believe that the first step to changing the world is to create safe spaces where people are deeply heard and seen. When stories are heard and seen, we begin to share our vulnerabilities and showing that side of ourselves is an act of love. Through this collectiveness, this solidarity, we fight for collective liberation.”