Qwertyman for Monday, February 3, 2025

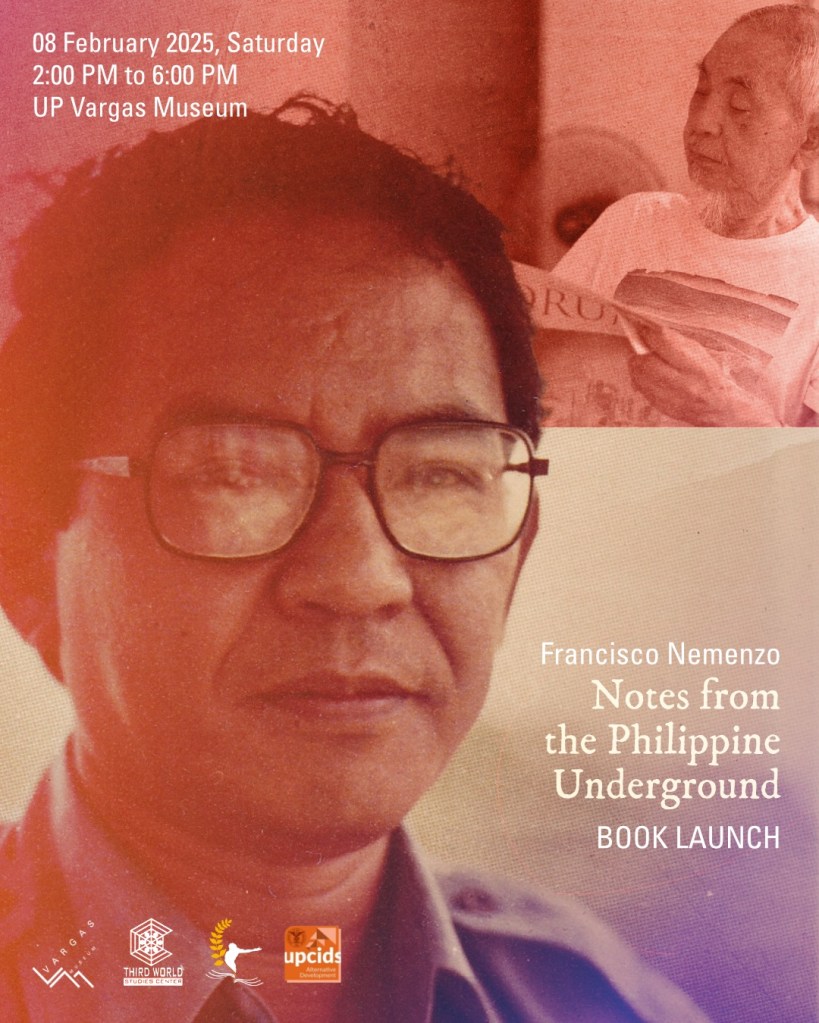

I DON’T know if there’s a Marxist heaven, but if there is, then Dr. Francisco “Dodong” Nemenzo, who passed away recently, must be smiling up there because of the forthcoming launch of his book Notes from the Philippine Underground (UP Press, 2025).

It’s too bad that Dodong won’t be around to see the book and sign copies for his legions of friends and comrades—many of them like my wife Beng, who remember him as a dashing and persuasively articulate professor of Western Thought, despite the Cebuano-accented English he was sometimes laughed at for by the ignorant. He never became my teacher in college, and oddly enough—because I was out of UP Diliman for most of the time he was teaching there—I never really got to know him closely as an activist and ideologue.

I did know him as a boss—he took me in as his Vice President for Public Affairs when he was UP President—and in that capacity I learned to respect and admire him as a man who held firm to his principles while finding practical and effective solutions to UP’s problems. This was especially true of our campaign to revise the outdated UP Charter, which eventually succeeded under President Emerlinda Roman, but which he tenaciously pursued despite the insults of spiteful politicians.

Throughout his adult life and to the last, Nemenzo remained a professed and unapologetic Marxist—a word that would seem Jurassic in these post-Soviet and Trumpian times, but which he saw and lived in a different light.

As the preface to his book by Prof. Patricio “Jojo Abinales” explains, “Dodong’s engagement with Marxist theory wasn’t an academic exercise. For him, Marxism was a living, breathing framework—a summons to connect theory to the existing conditions of everyday life. He wasn’t content to theorize from a distance; with a scientific mind, he dug into the realities of Philippine society, always interrogating its dominant ideas, structures, and contradictions. His writings speak to this dual commitment: the rigor of his analysis is matched by an acute sensitivity to the concrete lives of real people whose struggles he sought to illuminate. He distrusted all dogma, and sought to validate all received knowledge.

“Francisco ‘Dodong’ Nemenzo’s life and work resist easy categorization. He was a Marxist thinker, a revolutionary activist, an inspiring academic leader, and a mentor to generations of scholars and radicals. But more than any of these roles, he was a relentless questioner of the world as he found it—and a passionate believer in its potential to be different, if not better.”

Indeed the book shows how sharp, even scathing, Dodong could be in his opinions of how his idea of Marxism remains relevant and useful despite how it has been misused by many of its adherents and misunderstood by its opponents.

He writes: “We must struggle against their misconception of Marxist theory and practice (e.g., equating Marxism with Stalinism and totalitarianism) and point out that humanism is inherent in the Marxist worldview. Going through the basic documents of Filipino social democratic groups, it is obvious that, even as they try to distance themselves from Marxism, their analysis of present conditions and their historical roots is almost entirely based on a Marxist framework.”

He acknowledges the flaws and failures of Marxist parties caught up in internal conflicts (Dodong himself was once ordered to be executed by the party he belonged to, ostensibly for treason): “Can people be blamed for suspecting that communists are motivated by cynical calculations of what would bring them tactical advantages? Their loud and monotonous protestations ring hollow in the absence of inner-party democracy. The authoritarian and repressive character of the regimes their comrades established wherever they gained the upper hand reinforced this impression. This stigma they must shake off; otherwise they would remain at the periphery in the continuing struggle for democracy.”

He is not without wry humor. Reflecting on the ultimate folly of a revolution being led by a highly secretive, centralized, and “conspiratorial” party, he notes: “This is difficult to implement in the Philippine cultural milieu. A code of silence—what the Russians call konspiratsiya and the Mafiosi call omerta—is impossible among people who take rumor-mongering as a favorite sport. Our irrepressible transparency is a weakness from one point of view but a virtue from another. Our legendary incapacity to keep secrets is probably the best guarantee that no conspiratorial group can stay in power long enough to consolidate a dictatorship.”

Even for those disinclined or even hostile toward the Left, Notes from the Philippine Underground offers many valuable insights from one of that movement’s “OGs,” in today’s youth-speak. Nemenzo may be highly critical but he remains ultimately hopeful that positive and deep social change will happen, if the Left learns from its mistakes and finds new ways to engage society. Listen:

“There have been many pseudo-united fronts put up by the vanguard party. They consist of party-led mass organizations that simply echo the party line. None ever grew into a genuine united front, although they did attract a few prominent individuals who had no organizational base whatsoever. Other organized groups are often suspicious of the party and wary of being reduced into instruments for policies they do not accept.

“But I know of only three attempts at seriously establishing a real united front in this country: in the immediate postwar period, in the late 1960s, and very recently. They all collapsed because of sectarian methods of work. Sectarianism is the blight of all united front efforts everywhere….

“The Philippine movement has never been able to solve this dilemma. At the very moment when united front structures are set up, rivalries emerged. And intoxicated by short-term successes in expanding their mass organizations, the sectarians eventually prevailed.”

Pluralism, he suggests, is key: “Pluralism is a bourgeois liberal doctrine that ought to be preserved and enriched in the socialist revolution. It is not incompatible with socialism. The tension that arises through political competition would serve as a constant reminder that the party must earn the allegiance of the masses. Of course, no state would tolerate an opposition party that resorts to violent methods and solicits support from foreign powers. But this should never be an excuse for suppressing any opposition.”

Surely there will be blowback from those holding different views; expect the usual howl from UP bashers and red-taggers. But when that happens, even from the grave—or Marxist heaven—Dodong Nemenzo will have sparked the kind of discussion we direly need to find our way forward as a nation.