Qwertyman for Monday, March 6, 2023

TODAY WE pause our fictional forays to focus on some happily factual news—the visit last Thursday of Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim to the University of the Philippines, which conferred on him an honorary Doctor of Laws degree.

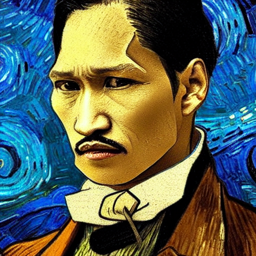

I’ve been missing many university events especially since I retired four years ago, but I made it a point to attend this one because I’ve long been intrigued by Anwar’s colorful if mercurial political career—one that witnessed his meteoric rise from a student leader (who majored, at one point, in Malaysian literature) to minister of culture, youth, and sports, then of agriculture, and then of education, before being named Finance Minister and Deputy Minister in the 1990s.

As Finance Minister during the Asian financial crisis of 1997, Anwar imposed very strict measures to keep the Malaysian economy afloat—denying government bailouts, cutting spending, curbing corruption and calling for greater accountability in governance. His zeal and effectiveness gained him international recognition—Newsweek named him Asian of the Year in 1998—and put him on track to succeed his mentor Mahathir Mohamad as Prime Minister.

However, his growing popularity came at a steep personal price. In what he and his supporters denounced as political persecution, he was imprisoned twice following a fallout with Mahathir. In the meanwhile, Malaysia sank into a morass of corruption under the since-disgraced Najib Razak, making possible the brief return to power of Mahathir, who enabled the release of his sometime protégé Anwar. Anwar’s eventual accession to the prime ministership in December 2022 was for many a just culmination of decades of near-misses (in our lingo, naunsyami).

His visit to Diliman last week was actually a homecoming. Anwar had visited UP more than once as a young student being mentored by the late Dr. Cesar Adib Majul, our leading specialist in Islamic studies. Like other Malaysian scholars, Anwar has also had a deep and lifelong appreciation for the life and work of Jose Rizal, with whom he shared the notion of a pan-Asian community of interests.

Most instructive was the new UP President Angelo Jimenez’s summation of Anwar’s political philosophy, in his remarks welcoming and introducing the PM:

“Beneath Anwar Ibrahim’s sharp sense of financial management lies a deep well of moral rectitude, a belief in right and wrong that seems to have deserted many of today’s political pragmatists. Much of that derives from his strong religious faith—which, unlike the West, he does not see as being incompatible with the needs and priorities of modern society. To him, this is a native strength that can be harnessed toward an Asian Renaissance.

“Like Jose Rizal, who self-identified as ‘Malayo-Tagalog’ and who was a keen student of the cultural and linguistic connections between Malays and his own countrymen, Anwar appreciates the West as a source of knowledge but cautions against neglecting or yielding our cultural specificity.

“At the same time, he has championed a more inclusive and pluralistic Malaysia, arguing—and here I quote from his book on The Asian Renaissance—’not for mere tolerance, but rather for the active nurturing of alternative views. This would necessarily include lending a receptive ear to the voices of the politically oppressed, the socially marginalized, and the economically disadvantaged. Ultimately, the legitimacy of a leadership rests as much on moral uprightness as it does on popular support.’”

In his talk accepting the honorary degree, Anwar argued strongly and eloquently for the restoration of justice, compassion, and moral righteousness to ASEAN’s hierarchy of concerns, beyond the usual economic and political considerations. He was particularly critical of ASEAN’s blind adherence to its longstanding policy of non-interference in its members’ internal affairs, noting that “ASEAN should not remain silent in the face of blatant human rights violations” and that “non-interference cannot be a license to disregard the rule of law.”

Extensively quoting Rizal, whom he had studied and lectured often about, Anwar urged his audience to free themselves from the self-doubt engendered by being colonized, while at the same time remaining vigilant against subjugation by their “homegrown masters.” I found myself applauding his speech at many turns, less out of politeness than a realization that I was in the presence of a real thinker and doer whose heart was in the right place. (And Anwar was not without wry humor, remarking that as a student leader visiting UP, “I was under surveillance by both Malaysian and Philippine intelligence. Now I have the Minister of Intelligence with me.”)

Speaking of honorary doctorates, I recall that UP has had a longstanding tradition of inviting newly elected presidents of the Republic, whoever they may be, to receive one, as a form of institutional courtesy. As soon as I say that, I realize that many readers will instantly recoil at the idea for reasons I need not elaborate upon. But let me add quickly that not all Malacañang tenants have accepted the honor. Some have had the good sense to find a reason to decline, knowing the kind of reception they will likely get from Diliman’s insubordinate natives, beyond the barricades that will have to be set up for their security. For everyone’s peace of mind, I humbly suggest that it may be time to retire this tradition, which agitates all but satisfies no one.

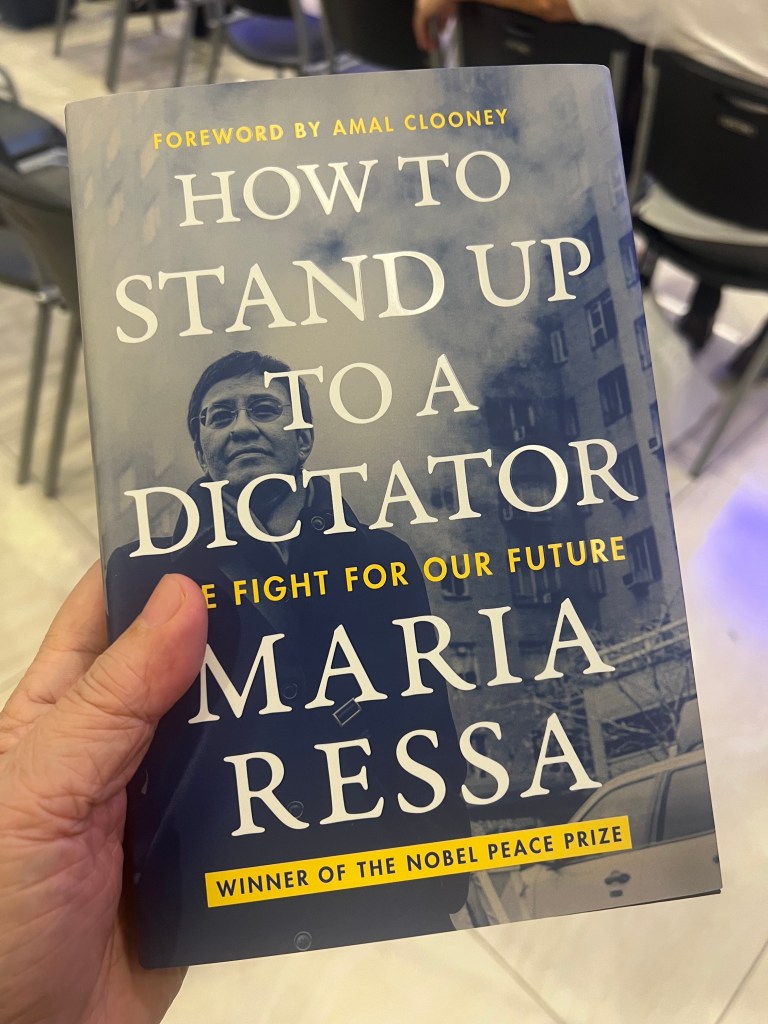

For the record, UP has given honorary doctorates to less than stellar recipients, including the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaucescu and the martial-law First Lady Imelda R. Marcos. Even some recent choices have stirred controversy and dismay.

As a former university official, a part of me understands why and when a state university dependent on government funding employs one of the few tools at its disposal for making friends and influencing people. But as a retired professor who has devoted most of his life to UP and its code of honor and excellence, I find the practice unfortunate if not deplorable.

I don’t make the rules, but if I did, I would automatically exclude incumbent Filipino politicians, Cabinet members, and serving military officers from consideration. This is not to say that they cannot be deserving, as some surely are, but that they can be properly recognized for their accomplishments upon leaving office. This will also leave much more room for the university to hail truer and worthier achievers of the mind and spirit—scientists, artists, scholars, civil society leaders, entrepreneurs, other outstanding alumni, and fighters for truth, freedom, and justice in our society.